Cultivate creativity and inspiration in your classroom with lessons learned at Pixar Animation

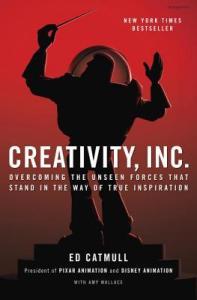

Ed Catmull’s Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration (Random House, 2014) Here is the supporting website. Add your favorite titles to the Artistic Thinking Bookshelf.

The jacket copy for Creativity, Inc. positions the book as a business management resource on how to build a sustainable creative culture. It reads,

Creativity, Inc. is a book for managers who want to lead employees to new heights, a manual for anyone who strives for originality, and the first-ever trip into the nerve center of Pixar Animation—into the meetings, postmortems, and “Braintrust” sessions where some of the most successful films in history are made. It is, at heart, a book about how to build a creative–culture but it is also, as Pixar co-founder and president Ed Catmull writes, “an expression of the ideas that I believe make the best of us possible.

That is a wise way to posit ion a book for broad appeal and maximum profit. But, that positioning excludes a great many who could benefit from its lessons and stories. It would be equally fair for the copy to read, “Creativity, Inc. is a book for educators who want to build sustainable creative cultures in their classrooms. It is for teachers who want to cultivate inquiry learning environments where students collaborate on dynamic group projects. It is for writing teachers who want to teach students that revision is oftentimes the only way to grow “ugly babies” into compelling works. It is for school principals who need to strategically feed the hungry beast (think standards and testing) while safeguarding the important work of their learning community. It is for administrators who want to implement powerful school reform that involve all stakeholders in their best analytical and creative thinking.

ion a book for broad appeal and maximum profit. But, that positioning excludes a great many who could benefit from its lessons and stories. It would be equally fair for the copy to read, “Creativity, Inc. is a book for educators who want to build sustainable creative cultures in their classrooms. It is for teachers who want to cultivate inquiry learning environments where students collaborate on dynamic group projects. It is for writing teachers who want to teach students that revision is oftentimes the only way to grow “ugly babies” into compelling works. It is for school principals who need to strategically feed the hungry beast (think standards and testing) while safeguarding the important work of their learning community. It is for administrators who want to implement powerful school reform that involve all stakeholders in their best analytical and creative thinking.

Teacher book study can be an effective way to foster a culture of professional development. Oftentimes the books read offer explicit strategies on how to achieve set instructional goals. Creativity Inc. is not one of those books. While it is not a cookbook for cultivating classroom creativity, Creativity, Inc. offers guiding principles and strategies teachers can build on.

Whether your title is manager or a teacher, the ultimate goal is to create an environment of inquiry. As Catmull explains,

We realized that our purpose was not merely to build a studio that made hit films but to foster a creative culture that would continually ask questions.

And whether you are a worker or a student, pursuing the unknown and challenging the status quo is fraught with anxiety and fear. Catmull reminds managers and teachers alike that a nurturing environment needs to recognize the fear of uncertainty, and teach strategies for learning from failure.

Rather than trying to prevent all errors, we should assume, as is almost always the case, that our people’s intentions are good and that they want to solve problems. Give them responsibility, let the mistakes happen, and let people fix them. If there is fear, there is a reason – our job is to find the reason and to remedy it. Management’s job is not to prevent risk but to build the ability to recover.

Creative endeavors need to make revision a way of life. Truly creative art projects, writing assignments, and science experiments rarely come together perfectly on the fist attempt. Identifying shortcomings and reconceiving alternative approaches to a challenge are a fundamental part of the creative process. Catmull explains that Pixar’s movies regularly traversed a long meandering path as it went “from suck to not suck.”

I’m not trying to be modest or self-effacing by saying this. Pixar films are not good at first, and our job is to make them so—to go, as I say, “from suck to not-suck.” This idea—that all the movies we now think of as brilliant were, at one time, terrible—is a hard concept for many to grasp. But think about how easy it would be for a movie about talking toys to feel derivative, sappy, or overtly merchandise-driven. Think about how off-putting a movie about rats preparing food could be, or how risky it must’ve seemed to start WALL-E with 39 dialogue-free minutes. We dare to attempt these stories, but we don’t get them right on the first pass. And this is as it should be. Creativity has to start somewhere, and we are true believers in the power of bracing, candid feedback and the iterative process—reworking, reworking, and reworking again, until a flawed story finds its throughline or a hollow character finds its soul.

And while describing some of the expansive company-wide initiatives Pixar instituted, Catmull also shares the everyday shifts that anyone can implement to cultivate creative thinking. For example, he explains how simply rephrasing a question can open up someone’s thinking.

Instead of saying, “The writing in this scene isn’t good enough,” you say, “Don’t you want people to walk out of the theater and be quoting those lines?” It’s more of a challenge.”

While these strategies for cultivating creativity have broad application, Creativity, Inc’s informal case studies offer educators an added benefit. Because the case studies revolve around Pixar’s movies and beloved characters, they may have particular appeal for adolescents. For example, the backstory of Toy Story 2’s rough launch is full of teachable moments and could be used as a class reading assignment. (see Chapter 4: Establishing Pixar’s Identity, pages 66-82). In these 16 pages, students learn how the movie moved from one ill-conceived idea, to a story arc that didn’t hold up, to a painstaking revision process, to a final product that gloriously defined the company. The steps Catmull outlines run parallel to the writing process students are taught as they brainstorm, draft, revise, edit, and present a paper, only, in Pixar’s case, with a heightened sense of chaos, second-guessing, and risk. In addition to learning the importance of actively working this process, students witness the power of peer feedback and support. And they learn through this vivid account, a lesson teachers regularly strive to impart: writing and creative expression are dynamic social acts and success is built on a rich mix of introspection, collaboration, and a lot of hard work.

The Toy Story 2 backstory is also a coming of age tale. As the chapter title explains, these were the years when Pixar came into its own. For adolescents who are working hard to find their own voice, this story may have particular appeal. In this account Pixar executives navigate competing interests with each choice defining who they are and how they will respond to the next choice. And even though they try to use their values as a guide, growing imbalances necessitate regular reevaluation. Throughout, Catmull explores the concept of teamwork in a way that would inform practices in a corporate boardroom or on a field of play.

Still not sure if Creativity, Inc. has application in your classroom or for your teaching practice? See if these excerpts resonate for you. It may help to change “manager” to “teacher” and “employees” to “students.”

Cultivating trust and embracing uncertainty

I believe the best managers acknowledge and make room for what they do not know—not just because humility is a virtue but because until one adopts that mindset, the most striking breakthroughs cannot occur. I believe that managers must loosen the controls, not tighten them. They must accept risk; they must trust the people they work with and strive to clear the path for them; and always, they must pay attention to and engage with anything that creates fear. Moreover, successful leaders embrace the reality that their models may be wrong or incomplete. Only when we admit what we don’t know can we ever hope to learn it.

Addressing fear and failure

The goal is to uncouple fear and failure — to create an environment in which making mistakes doesn’t strike terror into your employees’ hearts.

Fostering diverse thinking

The leaders of my department understood that to create a fertile laboratory, they had to assemble different kinds of thinkers and then encourage their autonomy. They had to offer feedback when needed but also had to be willing to stand back and give us room.

Creating a fertile environment that encourages creativity

The way I see it, my job as a manager is to create a fertile environment, keep it healthy, and watch for the things that undermine it. I believe, to my core, that everybody has the potential to be creative—whatever form that creativity takes—and that to encourage such development is a noble thing.

Balancing chaos and structure

I’m a firm believer in the chaotic nature of the creative process needing to be chaotic. If we put too much structure on it, we will kill it. So there’s a fine balance between providing some structure and safety—financial and emotional—but also letting it get messy and stay messy for a while. To do that, you need to assess each situation to see what’s called for. And then you need to become what’s called for.

Author Talks about Creativity, Inc. Overcoming the Unseen Forces that Stand in the Way of True Inspiration

- A discussion (1:19:41) at the Milken Institute forum

- A conversation (:59:30) with Stanford Professor Bob Sutton

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.