To bring my carvings to eye level, I experimented with pedestals that further accentuated the inherent characteristics of a stone.

When I was carving my field stones sculptures they sat on chest-level high carving stands. I got to know these sculptures on a face-to-face basis, so it struck me as a little strange to finish them and set them on the floor. While they now nestle around the house in corners and under furniture like pets curled up for a nap, I originally wanted others to meet them the way I knew them. The first time I showed them, I placed them on generic gallery pedestals—white, rectangular cubes. The cubes were bigger than the sculptures. And while they were designed to be anonymous, they still competed for space, if not attention. Couldn’t I have pedestals that figuratively and literally elevated the work?

Fortunately, Brancusi had already grappled with this issue. Brancusi had experimented with ways to use rough hewn timbers to not only support, but accentuate through contrast, his sleek, highly-polished sculptures. He used a small delicate cylinder as a perch that helped his Bird in Space defy gravity.

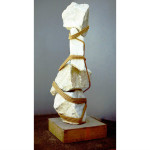

I began to explore pedestals that physically and conceptually reinforced and complimented my stone carvings. I found a discarded radiator whose ornamental detail accentuated the simple line of a leopard pattern stone. A black cube and plank offered asymmetrical support that underscored the missing “yang” to the stone’s “yin”. For another sculpture I carved a tree stump body that echoed the bulbous Sentry’s head. I also created an ice pedestal that overtime exposed the stone within, just as the glacier had done so many thousands of years before. Stacked and Bound used rope and raw chunks of marble to create its own free-standing sculptural form.

The value of a good pedestal

A wild ram would periodically come out of the woods that surrounded my boyhood home like a mythological creature. His coat was long and twisted, hanging off him like dreadlocks. A swarm of mosquitoes enveloped his head. He was a vision of agitation.

In his vexed state he fixated on the human-like Sentry outside our front door. He would circle it menacingly and then charge, launching his full form into the Sentry’s torso. Since the pedestal is a carved tree stump with its roots still firmly implanted, it didn’t budge, though the head wobbled back and forth seeming to taunt the ram.

In an attempt to scare the ram away, my mother would go into the yard clapping her hands together. The ram clearly misinterpreted this gesture for applause and continued to accost the sculpture until it tired. The sculpture never toppled.

There is an incredible amount to be learned about art and reimagining the expected through a close analysis of Brancusi’s pedestals. One way to do this is let the acclaimed artist and art critic Scott Burton be your guide.

Scott Burton’s essay My Brancusi offers an opportunity to combine close reading and close sculptural analysis. This essay from the show of the same name lets you view the art and “pedestals” of one of the 20th centuries greatest sculptors through Scott Burton’s highly trained eyes. As a class, delve into this essay, unpacking each point while viewing the works discussed.

Then consider Burton’s own work and how the sensibility from the essay manifests itself in his art, especially his “furniture” sculptures. This short video of one of his last pieces ties many these themes together. This site offers a broad overview of his work.