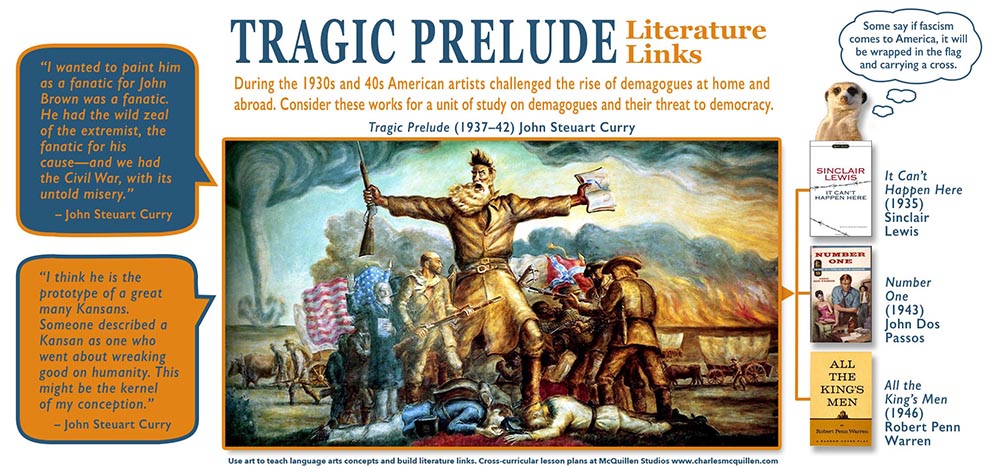

Teach close reading skills, symbolism, and shifting historical “truths” with John Steuart Curry’s Tragic Prelude

Tragic Prelude is part of John Steuart Curry’s mural project for the Kansas State Capitol. Visit their website for detailed information. Click on the painting for a larger, high quality image.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 overturned the Missouri Compromise (1820) that prohibited slavery in the Louisiana Purchase Territory north of 36°30’ parallel. Instead, Congress decided that the settlers should vote to determine whether slavery would be allowed in each state. Hoping to sway the vote, pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers flooded into the territory of Kansas, including the ardent abolitionist John Brown and his sons. In addition, “border ruffians” from neighboring Missouri bullied their way into the territory to vote illegally, helping elect a pro-slavery legislature. As violence escalated, guerrilla warfare ensued. On May 21, 1856, a pro-slavery militia sacked the “free soil” town of Lawrence, Kansas burning the hotel and destroying its anti-slavery presses. Already frustrated by political compromises and the pacifism of the organized abolitionist movement, these events spurred John Brown to fight violence with violence. On the night of May 24, Brown led a brutal attack on a pro-slavery settlement at Pottawatomie Creek, hacking five men to death with broad swords. Viewing himself as a soldier of a just God, Brown called for a righteous revolution against slavery. With each daring attack, Brown’s celebrity grew throughout the Northeast. The New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley coined the term “Bleeding Kansas” to describe the violent political confrontations that overwhelmed the territory, inflamed passions across the United States, and dragged the nation toward Civil War.

— John Brown and Bleeding Kansas (2:13) offers a concise video overview of these historic events.

The country had before this learned the value of Brown’s heroic character. He had shown boundless courage and skill in dealing with the enemies of liberty in Kansas. With men so few, and means so small, and odds against him so great, no captain ever surpassed him in achievements, some of which seem almost beyond belief.…With just thirty men on another important occasion during the same border war, he met and vanquished four hundred Missourians under the command of Gen. Read. These men had come into the territory under an oath never to return to their homes till they had stamped out the last vestige of free State spirit in Kansas; but a brush with old Brown took this high conceit out of them, and they were glad to get off upon any terms, without stopping to stipulate.…If John Brown did not end the war that ended slavery, he did at least begin the war that ended slavery. If we look over the dates, places and men, for which this honor is claimed, we shall find that not Carolina, but Virginia – not Fort Sumpter, but Harper’s Ferry and the arsenal – not Col. Anderson, but John Brown, began the war that ended American slavery and made this a free Republic. Until this blow was struck, the prospect for freedom was dim, shadowy and uncertain. The irrepressible conflict was one of words, votes and compromises. When John Brown stretched forth his arm the sky was cleared. The time for compromises was gone – the armed hosts of freedom stood face to face over the chasm of a broken Union – and the clash of arms was at hand. The South staked all upon getting possession of the Federal Government, and failing to do that, drew the sword of rebellion and thus made her own, and not Brown’s, the lost cause of the century.

—Frederick Douglass, John Brown: An Address at the Fourteenth Anniversary of Sorer College, Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, May 30, 1881. (While this excerpt has visual parallels with Curry’s Tragic Prelude there are no records that show Curry ever read this.)

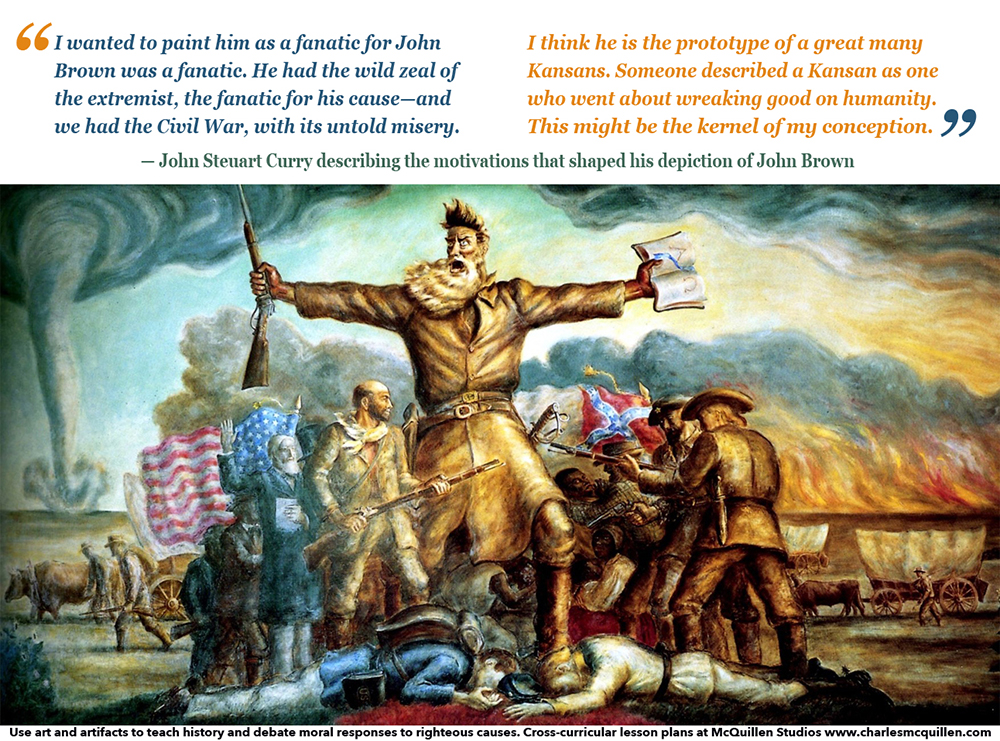

Centered on the north wall (31’x11’ 6”) is the gigantic figure of John Brown. In his outstretched left hand the word of God and in the right a “Beecher’s bible.” Beside him facing each other are the contending free soil and pro-slavery forces. At their feet, two figures symbolic of the million and a half dead of the North and South. In this group is expressed the fratricidal fury that first flamed on the plains of Kansas, the tragic prelude to the last bloody feud of the English-speaking people. Back of this group are the pioneers and their wagons on the endless trek to the West, and back of all the tornado and the raging prairie fire, fitting symbols of the destruction of the coming Civil War.

—John Steuart Curry, Description of Murals for Kansas State House, circa 1937–1942, John Steuart Curry and Curry family papers, 1900–1999. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, (Notes and Writings, Box 4, Folder 23).

Look at Tragic Prelude. Before reading the excerpts above, tell students the title of the piece and ask what is going on in this picture? This mural is full of symbols and emotions students may recognize. See how much students can decipher through a group discussion. Encourage students to identify the evidence that supports their reasoning. Students should likewise be encouraged to share wonderings and voice confusions. As the conversation slows, explain you are going to read excerpts about the events depicted. After reading the excerpts ask how does this new insight change your understanding of the painting?

Note: To anticipate an obvious question from the Curry excerpt, explain that “Beecher’s bibles” was the name given to the breech loading Sharps rifles that abolitionist and minister Henry Ward Beecher (brother of Uncle Tom’s Cabin author Harriet Beecher Stowe) supplied to the anti-slavery immigrants in Kansas. The rifles were called “bibles” because they were sometimes shipped in boxes disguised as books and Beecher felt they had more moral agency with corrupt slaveholders than actual bibles.

Begin with art history

John Steuart Curry was the eldest of five children in a deeply religious farm family from Dunavant, Kansas (November 14, 1897). This upbringing instilled in him a love of the land, a respect for perseverance and hard work, and a fluency in biblical stories. As he explained,

It’s the iron in those farmers such as my father and mother that I’d like to bring to paintings. If I can do that it’ll be better, to me, than painting something pretty.

While the farm animals and people of Kansas inspired his earliest work, he traveled the world to learn his craft. After five years of working as a magazine illustrator in New Jersey and a year of study painting techniques in Paris, Curry traveled with the Ringling Brothers Circus drawing and painting the performers, eventually settling in Westport, Connecticut. During the 1920s and 30s his paintings of Kansas life were met with critical and financial success.

My sole interest and conception of subject matter deals with American life, its spirit and its actualities.

While Curry painted the people and traditions from his boyhood, some Kansans misconstrued his observations as social satire. For these critics, his vivid depictions of tornadoes and religious fundamentalists perpetuated negative stereotypes of a state full of extreme weather and people. His rural nostalgia and romantic realism was celebrated as exotic by some and condemned as condescending by others.

The acclaim surrounding Thomas Hart Benton’s Missouri statehouse murals inspired Kansas cultural leaders to tap their native son to do the same for their statehouse. For his mural Curry chose an historical theme that chronicled pregnant moments in Kansas history against a backdrop of man’s struggle with nature. The third of eleven panels marked Kansas’ role in launching the Civil War with a dramatic portrait of the abolitionist John Brown. Curry described his portrait this way,

I portray John Brown as a bloodthirsty, god-fearing fanatic and those who like him, represented on both sides, brought on the Civil War. From what I can read of the memoirs of the people who knew him, he was continually preaching violent revolution.

This unsavory portrait of a murderous John Brown was not the glorious depiction of Kansas history that some desired and caused such controversy that Curry never completed the remaining panels. Curry returned to his appointment as artist-in-residence at the University of Wisconsin, Madison and for the remainder of his all-to-short life worked under the sponsorship of the Agriculture school showing local farmers how art could be used to chronicle and enhance their rural culture and economy.

Look like an art critic

Tragic Prelude is part of Curry’s mural project for the Kansas State Capitol. If you can’t visit personally check out their site that offers a tour of the murals and the building.

The use of line

Point out and discuss: Line is the use of outlines, implied lines, and patterns of marks to create an identifiable path in an artwork. They are oftentimes used to lead the viewer’s eyes around the composition, organize significant elements, and communicate information. What lines do you see in Tragic Prelude and how does Curry’s use of line serve his intentions?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: All lines lead to or radiate from John Brown. The horizon line draws the viewer’s eyes from the edge of the panel to the cluster of figures around John Brown in the center of the composition. The clouds from an encroaching tornado on the left and wildfire on the right echo the horizon line. The extended arms of the supersized John Brown likewise create strong horizontal lines. The two opposing groups, the free soilers and the pro-slavery forces face each other, their sight lines, the lines of their rifles and flags converge on Brown. The heads of the opposing forces align with Brown’s belt. Even the dead soldiers lying straight along the picture plane meet head to head at Brown’s feet. The supersized Brown also creates a strong vertical line that serves as an axis on which the composition rotates. His coat strains from the force within as he gestures wildly with a rifle in one hand and a bible in the other. His twisting neck, the rippling lines in his coat, and his wind blown beard make him a force of nature that rivals the storm and smoke clouds on the horizon. Note how the clouds part around him. John Brown’s size and fury dominate the scene, sucking in the energy and focus of the other compositional elements. Curry depicts John Brown as a human cyclone wreaking havoc and destruction on the human landscape. The settlers in the middle ground show resilience and fortitude as they struggle on enduring the natural disasters in the background and the man-made disaster in the foreground.

Compare depictions of John Brown

As he [John Brown] stepped out of the door a black woman, with her little child in arms, stood near his way. His thoughts at the moment none can know except as his acts interpret them. He stopped for a moment in his course, stooped over, and with tenderness of one whose love is as broad as the brotherhood of man, kissed it affectionately.

—Edward H. House, a special correspondent for the New York Tribune (December 5, 1859), describing Brown’s final steps to the gallows after he was convicted of treason for his attack on the arsenal at Harpers Ferry, VA.

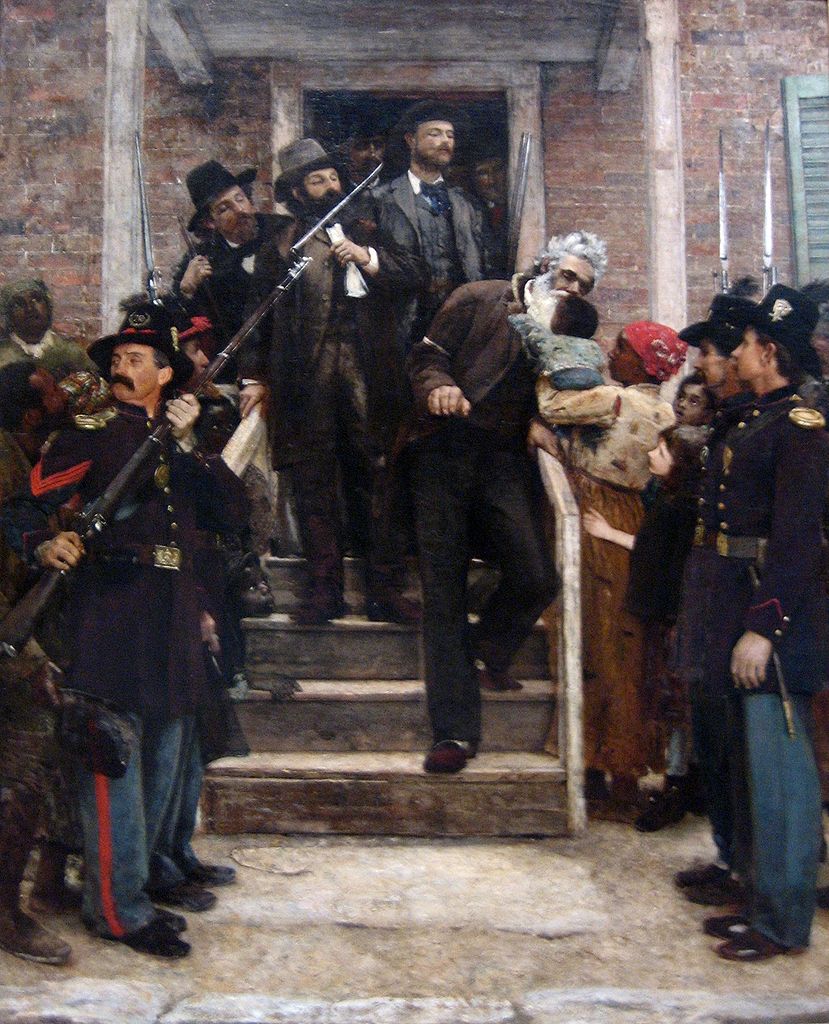

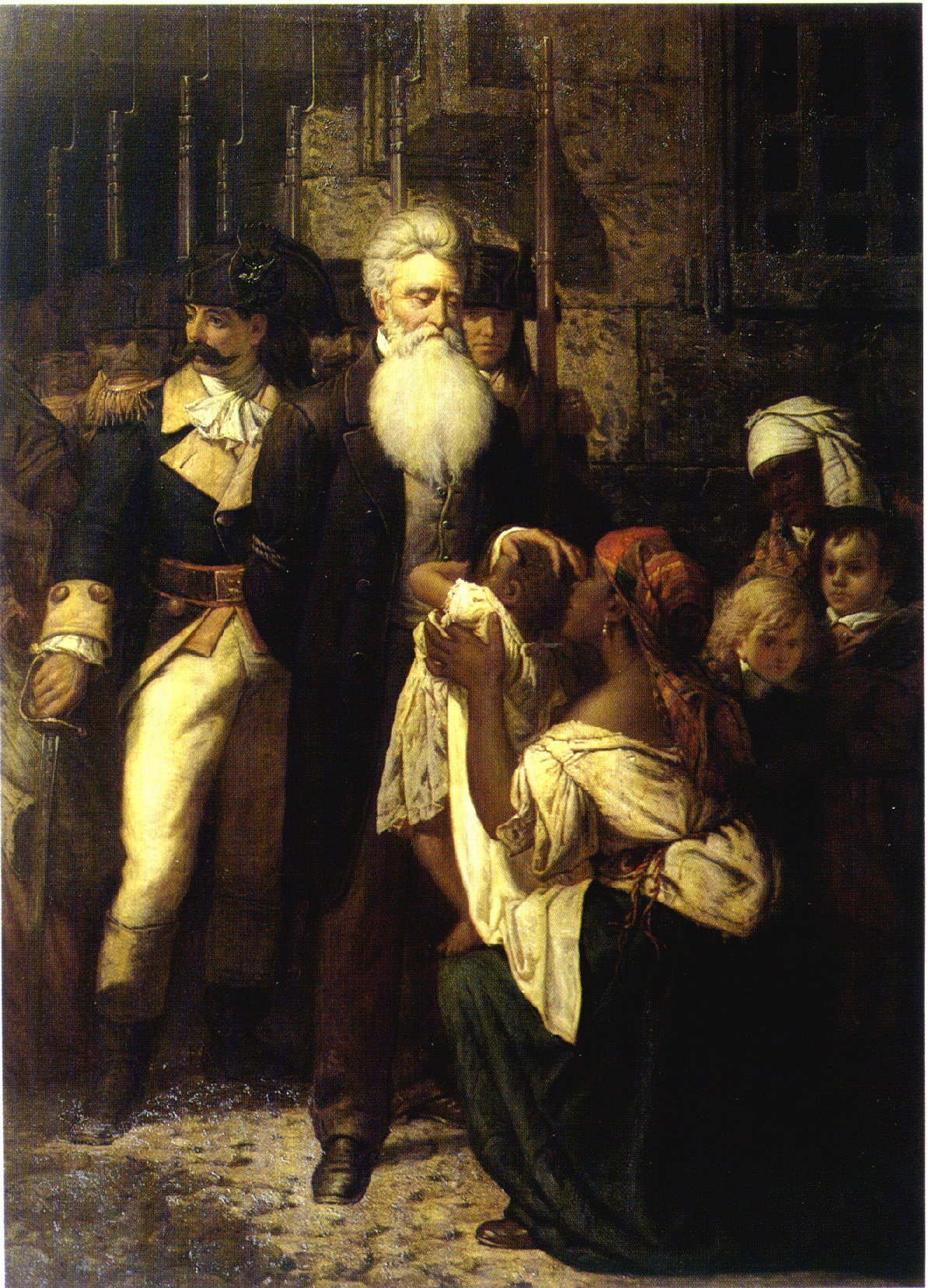

Point out and discuss: While dramatic, this scene was fabricated. Nevertheless, it inspired poets and artists for years to come and spawned a series of paintings and prints that drew on this imagery. Thomas Hovenden’s The Last Moments of John Brown (1884) may be the most celebrated of these and, ironically, is recognized as the most historically accurate. Curry’s alternative depiction of John Brown marks a dramatic break in this artistic tradition. How is Hovenden’s depiction of John Brown different than the one in Tragic Prelude? How does Curry’s depiction of John Brown serve his intentions?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: Hovenden’s John Brown looks like a kindly grandfather. He is stooped, slightly disheveled, wears slippers, and braces himself against the handrail as he dotes on the child. His white beard is Santa Claus-like. The earth tones are warm and soothing. The composition is organized around a stable pyramid. Brown identifies with the other vulnerable figures in the scene and stands in stark contrast to the soldiers who surround him with their uniforms and weapons, the glint off the bayonets make them especially menacing. Hovenden’s John Brown exudes love, tolerance, and compassion. He is peaceful. His white hair and beard envelope his head like a halo giving him a saintly disposition. This painting focuses on his cause, not his victims. Curry’s John Brown is dramatically different. He is considerably larger than the other figures, his arms extending over the scene. He gestures menacingly with a rifle in one hand and a sword on his hip. Confrontation is all around him as opposing forces face off. Dead soldiers lie at his feet. The focus is more on the conflict than the cause. While blacks are shown they are lost in the shadows in the background. His hands are bloodstained, hair is wild, his mouth open as if in a yell, his eyes bulge with emotion. He is a vision of turmoil, rage, and fury. He is so commanding and powerful that he seems to part the storm clouds. Curry wanted to highlight the fanatic side of John Brown that inspired righteous violence and escalated tensions. Curry didn’t show storms to celebrate them, rather he showed storms to celebrate the perseverance and fortitude Kansans exhibited in coping with them. His John Brown is a man-made storm that shaped the history and culture of Kansas.

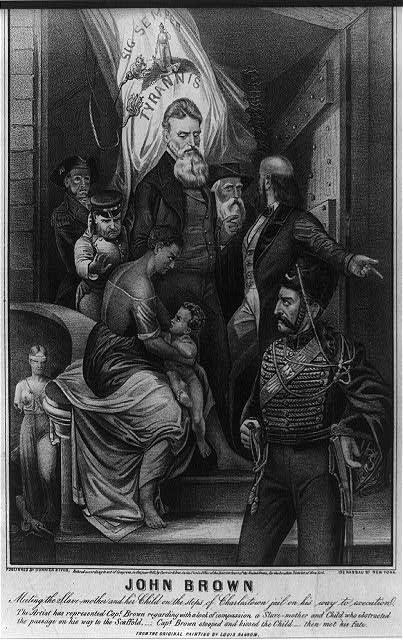

Extend this comparison with an analysis of art that fed the painting tradition Hovenden drew on. It underscores Curry’s dramatic break from tradition. Currier & Ives’ widely distributed print John Brown Meeting the Slave Mother and Her Child on the Steps of Charleston Jail on His Way to Execution (1863) was based on a painting by Louis Ransom. Thomas Satterwhite Noble’s John Brown’s Blessing (1867) is one in a series of four anti-slavery paintings by the former Confederate soldier. This news account also inspired John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem Brown of Ossawatomie. This poem basks in the divergent perspectives of the controversial abolitionist.

Compare war-themed paintings

Point out and discuss: The bulk of Curry’s paintings were created between the two world wars. So, it’s little wonder that some of his paintings had war themes. Consider The Return of Private Davis from the Argonne (1928–1940) and Parade to War (1938). Compare these war-themed paintings with Tragic Prelude. What do these paintings have in common? What worldview do you think Curry is expressing?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: The title The Return of Private Davis from the Argonne suggests a joyful, triumphant homecoming only to depict a heart wrenching burial scene. The tightly knit community huddles together with their heads bowed in mourning. The lush green landscape with clouds on the far horizon suggests the soldier died in a distant conflict. Parade to War likewise uses a sharp juxtaposition of discordant details to heighten an emotional response. At first glance you see the pageantry of a military parade. Flags and ticker tape flutter in the breeze. Excitable boys run along with sharply dressed soldiers marching in formation. A beautiful woman in white embraces a soldier. And then you notice the soldiers are skull faced. They are the walking dead and the young don’t seem to notice. In all three paintings you witness the senseless loss of life. The horrors of war are born by the soldiers and their extended families. Note the older women in the parade scene dressed in black with their heads bowed. All three paintings highlight flags as symbols of nationalism, implicating political leaders and blind patriotism. Tragic Prelude and The Return of Private Davis likewise implicate self-righteous fanatics. The priest at the burial stands in sharp contrast to the mourners as he pontificates, gesticulating to the heavens. All three painting explore man-made tragedy, suffering, and death. All three paintings warn against inflammatory rhetoric and foreign entanglements (remember the violence of Bleeding Kansas was instigated by outsiders). All three paintings were painted on the eve of WWII and express Curry’s isolationist America-first leanings.)

In a 1939 newspaper interview, Curry expressed his isolationist leanings and explained how his historical depiction of John Brown was created with an eye to the growing conflict in Europe. Because this statement answers the question above it might be better shared after students have an opportunity to analyze and respond to the war-themed paintings.

I wanted to paint him [John Brown] as a fanatic for John Brown was a fanatic. He had the wild zeal of the extremist, the fanatic for his cause—and we had the Civil War, with its untold misery. My grandfather, for instance, died of his wound received in the war. It is the fanatics, the people who insist on going to extremes who cause wars. The cast masses don’t want war—it never brings them any good. What a pity the differences that caused the Civil War were not settled peacefully and amicably. War and beauty do not go together. In the madness and hysteria of war artists are kept busy grinding out horrible atrocity pictures. I studied in Paris—but don’t think we ought to feel it our duty to go to war every time France and other European nations resume their 1,000 year-old quarrels.

While John Brown’s cause was righteous, were his efforts morally justifiable and strategically wise? Tragic Prelude explores that question just as the abolitionists did 80 years before and Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. would do 30 years later. It’s a worthwhile discussion for any citizenry, especially in a statehouse where the answers to this question have far-reaching implications.

Think Like an Artist

In a letter defending his depiction of John Brown, Curry wrote,

I think that I am historically correct when I portray John Brown as a bloodthirsty, god-fearing fanatic and those who like him, represented on both sides, brought on the Civil War.

Curry was wary of fanatics and demagogues who threatened to “wreak good on humanity” by inflaming violent opposition. Can you identify contemporary figures who fit this description? If you were going to co-opt the Tragic Prelude composition to depict this person, what symbols would you have them hold? What opposing forces or flags might be shown in the background? What victims might you show at their feet? What natural disasters might you include to evoke a regional context?

Life Lesson

Enjoy the ten-year journey to controlled craft.

In an address to the Art Association of Madison, Wisconsin, Curry explained the relationship between perseverance and creativity.

From my experience I advise that you sharpen your tools of craft, look behind the flashy and popular contemporary or stylish vogue to their sources, and paint pictures and then more pictures. It takes from five to ten years to develop a competent baseball player or prizefighter. A skilled acrobat goes into training at the age of three and reaches his best at about twenty-four—so in this art of painting you can allow yourself at least ten years of work before you can in your own mind feel the freedom and satisfaction of a controlled craft.

It takes a lot of practice to be good at complex tasks. In his book Outliers Malcolm Gladwell popularized the 10,000-hour rule. Mastery takes talent and preparation, lots and lots of preparation. 10,000 hours, or as Curry says “10 years,” may seem overwhelming. But this should not be seen as a grueling undertaking. Curry is much more nurturing when he says “allow yourself at least ten years of work.” That “allow” takes the pressure off. Yes, expect to do a lot of work and be diligent, but have realistic expectations, give yourself room to roam, and enjoy the journey.

Related Video

- American Experience’s Who Is John Brown? (1:56) provides an introduction to the abolitionist John Brown. This is an excerpt from their larger offering The Abolitionists.

- John Brown (9:55) offers a concise summary of the abolitionist’s antislavery efforts and the range of emotions he aroused.

- TED Ed’s How One Piece of Legislation Divided a Nation (6:02) uses smart infographics to connect the political dots and explain how the Kansas–Nebraska Act and John Brown, the poster boy of Bleeding Kansas, sparked the Civil War.

Integrating into Your Curriculum

Artists oftentimes use common visual strategies or signposts to alert viewers to significant details in their art. Here are some ideas for using these visual signposts to unpack a work of art. Remember, the close reading skills in art appreciation are similar to the close reading practices taught in reading.

Literature Links: What piece of literature would you partner with John Steuart Curry’s Tragic Prelude? Tragic Prelude offers a number of avenues for literary exploration. The wealth of primary source documents related to John Brown illuminates the man and his times.

- Senator Charles Sumner’s speech “The Crime Against Kansas” underscores the pivotal role Kansas played in the march to war and reflects the increasing polarization of America around the issue of slavery. The physical beating Sumner endured after the speech likewise spurred John Brown to violence and martyrdom.

- John Brown’s letter to his wife and children gives his accounting of typical frontier hardships and events in Bleeding Kansas. If you wish to target a few letters, note Oct. 14, 1855, Nov. 23, 1855, June 1856, and An Idea of Things in Kansas.

- Frederick Douglass’ John Brown: An Address at the Fourteenth Anniversary of Sorer College, offers a caring tribute from one abolitionist to another. At the same time, Douglass’ “My Opposition to War: An Address Delivered in London, England, on May 19, 1846” offers a counterpoint to Brown’s Christianity-inspired fanaticism that echoes in some ways Curry’s perspective.

- H. Clay Pate’s pamphlet John Brown describes Brown’s exploits in Kansas as criminal. This might be expected since Pate was a proslavery mercenary Brown tricked into unconditional surrender.

Another equally interesting avenue of literary exploration considers John Steuart Curry’s literary peers and their renewed interest in John Brown and their exploration of fanatics and demagogues.

- William Blackwell Branch’s play In Splendid Error (1954) explores the relationship between the abolitionists John Brown and Frederick Douglass and the different paths they followed in fighting slavery.

- Sinclair Lewis’ It Can’t Happen Here (1935), John Dos Passos’ Number One (1943), and Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men (1946) work at the edge of fiction and nonfiction chronicling the fragility of democracy and the rise of moralizing demagogues.

- E.B. Du Bois’ biography John Brown (1909) chronicles his life as a civil rights activist as a way to inspire others to continue the process of emancipation.

- While decades after Curry, The Autobiography of Malcolm X as Told to Alex Haley (1964) explores racism and the legitimacy of righteous violence as an agent of social transformation. Malcolm X and John Brown both shared a “by any means necessary” mentality toward securing racial equality.

Writing Opportunity: historical research and argument writing. Do you know Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art? It is a veritable intellectual national park and a real treasure. The John Steuart Curry and the Curry Family papers offer great opportunities to sift through primary source documents and engage in authentic historical research. Just as John Brown’s reputation and legacy was reappraised over time, so too did thinking around Curry’s Tragic Prelude. Reading these letters, writings, and newspaper clippings shows how politics and public opinion can cause our understanding of historical “truths” to shift over time. (Note: Reading cursive writing can be especially challenging for digital natives. Fortunately, most of these writings are typed.) Here is a gallery of articles Curry collected and his personal correspondence. Click on an image to look closer.

Writing Opportunity: historical research and argument writing. Do you know Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art? It is a veritable intellectual national park and a real treasure. The John Steuart Curry and the Curry Family papers offer great opportunities to sift through primary source documents and engage in authentic historical research. Just as John Brown’s reputation and legacy was reappraised over time, so too did thinking around Curry’s Tragic Prelude. Reading these letters, writings, and newspaper clippings shows how politics and public opinion can cause our understanding of historical “truths” to shift over time. (Note: Reading cursive writing can be especially challenging for digital natives. Fortunately, most of these writings are typed.) Here is a gallery of articles Curry collected and his personal correspondence. Click on an image to look closer.

- A series of letters from Kansas cultural and political leaders pitch the idea of the murals and describe the behind the scenes efforts and motivations for launching the mural project. (Correspondence, Box 2, Folder 39, note especially thumbnails #1 and 2.)

John Steuart Curry’s Description of Murals for Kansas State House, circa 1937–1942 chronicles what the artist intends to depict. (Notes and Writings, Box 4, Folder 23)

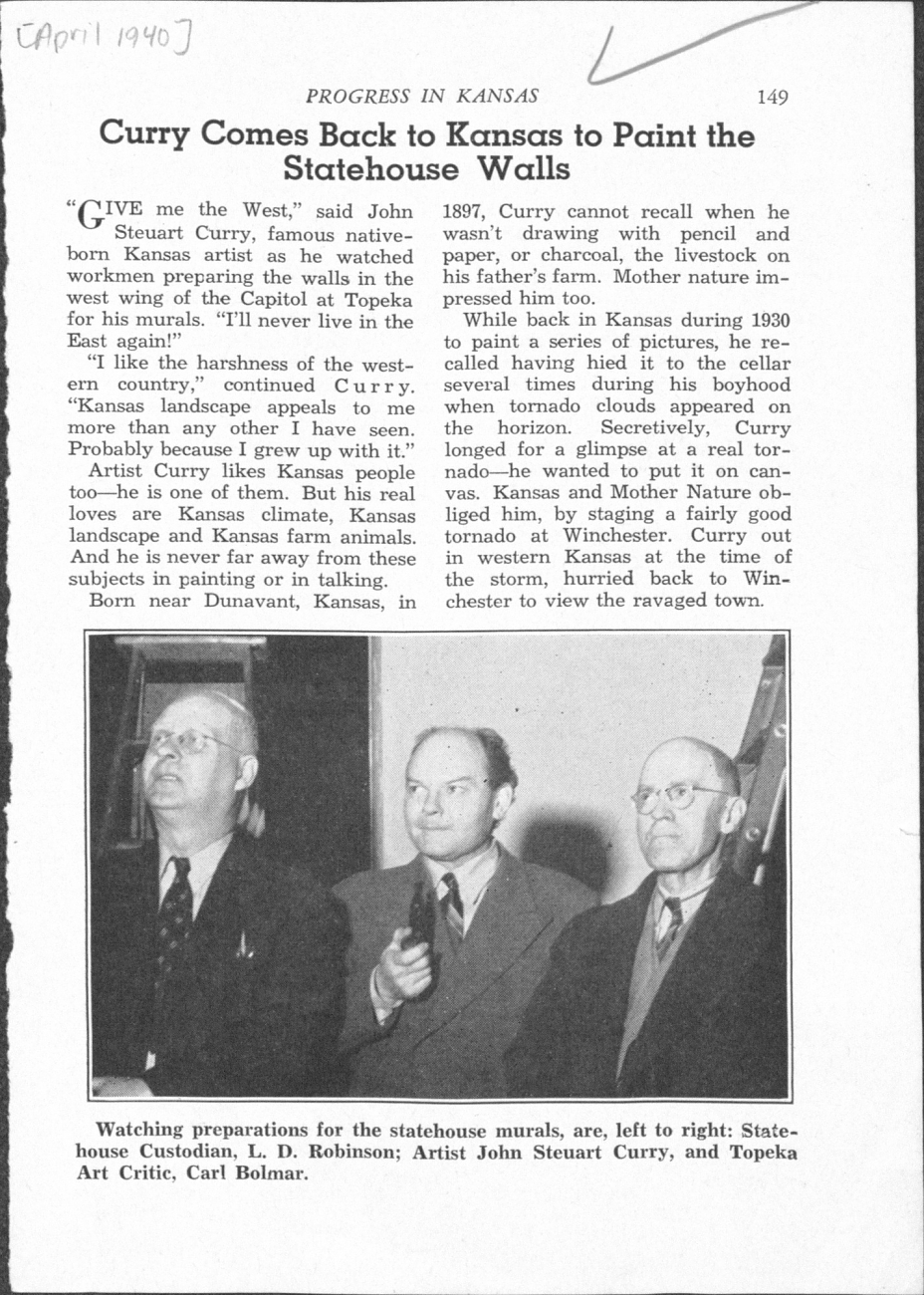

John Steuart Curry’s Description of Murals for Kansas State House, circa 1937–1942 chronicles what the artist intends to depict. (Notes and Writings, Box 4, Folder 23)- “Curry Comes Back to Kansas to Paint the Statehouse Walls,” Progress in Kansas, April 1940 expresses everyone’s high hopes at the beginning of the project. (Clippings 1940, Box 4, Folder 63)

- John Steuart Curry’s John Brown subject file includes the pictures and writings Curry collected as he prepared Tragic Prelude. Note that the Kansas John Brown was clean-shaven and that his characteristic, and expressive beard was only grown later to disguise his appearance. (Subject Files, Box 3, Folder 58)

- A series of letters give the first hints of problems in removing decorative marble slabs to make room for the murals. (Correspondence, Box 2, Folder 41, note especially thumbnails #10–11, 18–19, 30, and 45–49.)

- “Artist Curry Brushes Up on Subject of Pigtail Kinks,” _____ Sentinel, November, 11, 1940 describes how a farmer’s critique of Curry’s pigs sends him out to the farms to observe and sketch. (Clip

pings 1940, Box 4, Folder 63)

pings 1940, Box 4, Folder 63) - “John Brown’s Memory Marches On—As Kansas Battles Over Murals,” The Toledo Times June 23, 1941 chronicles the growing political discord around Tragic Prelude. (Clippings 1941, Box 4, Folder 64)

- A series of letters between Curry and supporters and opponents of the mural project offer insight into the rising tensions. (Correspondence, Box 2, Folder 44, note especially thumbnails #8, 12, 13, 20, 22–23, 21 & 24, and 25.)

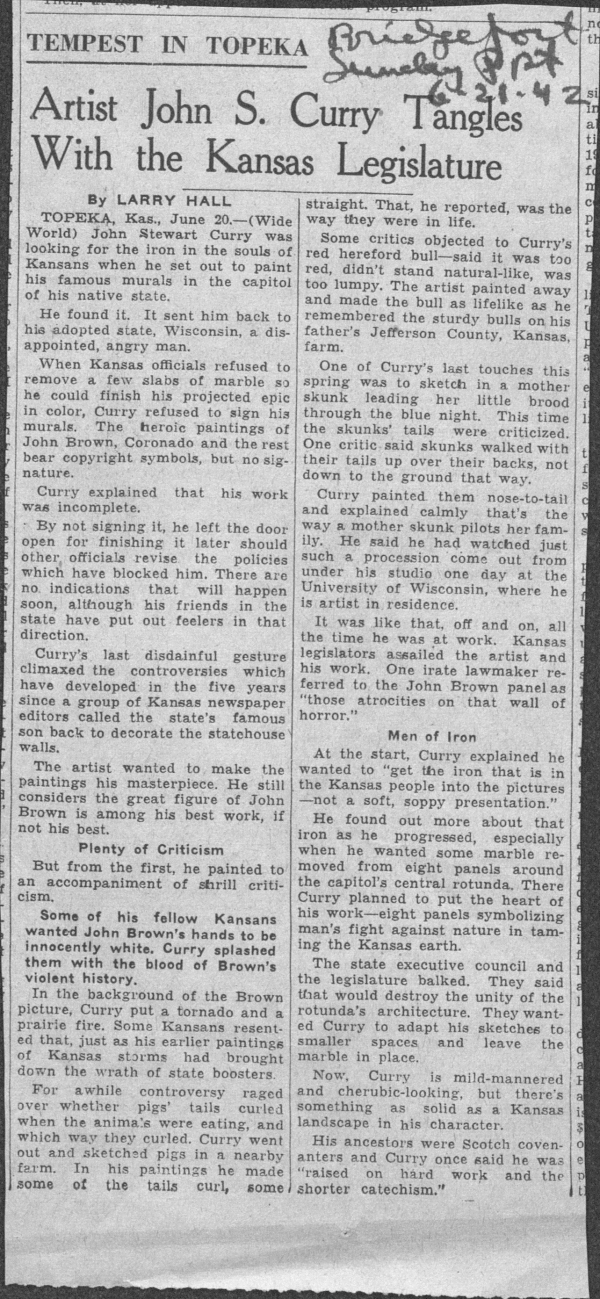

- “Artist John S. Curry Tangles with the Kansas Legislature” Bridgeport Sunday Post, June 21, 1942 details the mural controversy and why they were left unsigned. (Clippings 1942, Box 4, Folder 65)

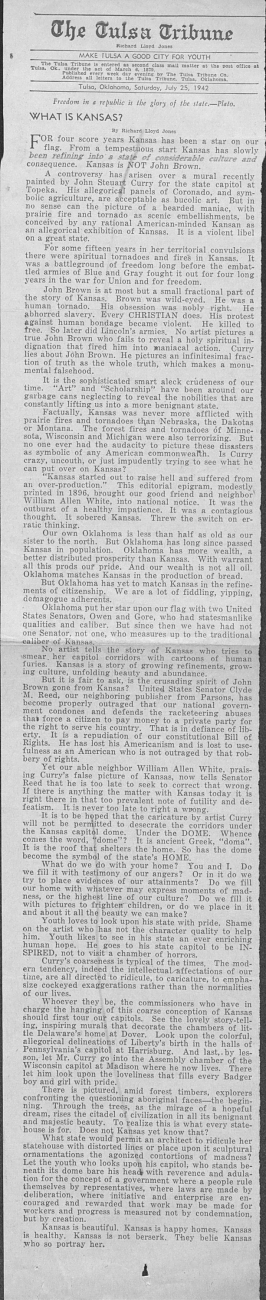

- Richard Lloyd Jones’ editorial “What Is Kansas?” The Tulsa Tribune, June 25, 1942, condemns the murals, especially the depiction of John Brown. (Clippings 1942, Box 4, Folder 65)

- Curry responds to Richard Lloyd Jones in a personal letter. (Correspondence, Box 2, Folder 45, note thumbnail #35)

- A series of letters between Curry and supporters and opponents of the murals detail the mounting acrimony, the frantic efforts to keep the project on track, and Curry’s failing health. (Correspondence, Box 2, Folder 46, note thumbnails #1, 5, and 18.)

- Thomas Hart Benton’s “Implications of Artist’s Reaction to Lack of Sympathy from His “’Ideal Audience.’” Kansas City Times, November 27, 1946 is an eloquent tribute from a dear friend and acclaimed artist who suffered similar criticism for his murals. (Clippings 1946, Box 4, Folder 68)

- “SAGE of the SAGA,” Topeka Capital Journal, October 16, 1977 describes how the artist Lumen Martin Winter was commissioned to complete the Curry murals. (Clippings 1976-78, Box 4, Folder 74)

- John Steuart Curry’s state house murals are declared one of the eight wonders of Kansas.

Have small groups read different letters and news accounts and plot key events on a class timeline that maps how support for the mural project evolved. (Also let students revel in the snarkiness as the drama builds. Curry’s zingers reflect his emotions and will remind students that history is about the struggles of real people.) As students share, capture their questions and points of interest. In addition to exposing varying, and deeply held, views of historic people and events, these documents provide insight into the use of argument writing, proxy arguments, and political maneuvering. If time and interest permits, have students research and respond to their questions.

Have small groups read different letters and news accounts and plot key events on a class timeline that maps how support for the mural project evolved. (Also let students revel in the snarkiness as the drama builds. Curry’s zingers reflect his emotions and will remind students that history is about the struggles of real people.) As students share, capture their questions and points of interest. In addition to exposing varying, and deeply held, views of historic people and events, these documents provide insight into the use of argument writing, proxy arguments, and political maneuvering. If time and interest permits, have students research and respond to their questions.

The Question Formulation Technique (QFT) can help turn art observations and wonderings into inquiry-based research questions that build on student insights and interests. For ideas on how to structure inquiry circles see Stefanie Harvey and Smokey Daniels’ Comprehension and Collaboration: Inquiry Circles for Curiosity, Engagement, and Understanding.

John Steuart Curry’s Tragic Prelude offers mentor art for teaching writers character development. View a lesson here.

How would you use this painting to build on one of your units of study? Please share if you have other ideas on how to teach Tragic Prelude by John Steuart Curry as an English/language arts lesson plan.

His roots

It’s the iron in those farmers such as my father and mother that I’d like to bring to paintings. If I can do that it’ll be better, to me, than painting something pretty.

— John Steuart Curry “Curry and Kansas—A Story of Heroic Life”, The Kansas City Star, August, 22, 1937, Society page 1, (Folder 61)

I like the harshness of the western country. Kansas landscape appeals to me more than any other I have seen. Probably because I grew up with it.”

— John Steuart Curry “Curry Comes Back to Kansas to Paint the Statehouse Walls”, Progress in Kansas, April 1940. (Folder 63)

I was raised on hard work and the shorter catechism. My father fattened cattle for the Kansas City markets, and the stock had to be cared for. We were up at four o’clock the year round feeding the steers, planting and plowing corn, cutting hay and wheat; and in the school months, doing half a day’s work before we rode to town on horseback to our lessons. But we didn’t mind. It was the only life we knew—and I had a good constitution.

— John Steuart Curry “John Steuart Curry”, Scribner’s, January, 1937, page 37

His views of John Brown

John Brown, the Traitor. John Brown, The Fanatic. John Brown, The Martyr. Thus has this man, one of the most dramatic characters of all time, been denounced and acclaimed. But regardless of the varying estimates of him, the great outstanding fact of his life and death is that it was he who crystallized sentiment that brought about the onslaught against the greatest curse that this nation has ever known, and its final eradication—human bondage.

— John Steuart Curry attributed quote by Max Moxley (I think it is originally by Albion Tourgee, though I can’t locate the source), Bulletin Sterling Kansas, June 3, 1976

You can read in the Kansas State Historical Society in John Brown’s own handwriting – I can’t state it exactly, but it goes somewhat like this – The curse of slavery cannot be erased from this land until it is erased in blood. I think that I am historically correct when I portray John Brown as a bloodthirsty, god-fearing fanatic and those who like him, represented on both sides, brought on the Civil War. From what I can read of the memoirs of the people who knew him, he was continually preaching violent revolution.

—John Steuart Curry in a letter to Reverend A. H. Christensen (January 12, 1940)

I judge from the press clippings that some of the legislators are very much disturbed about my presentation of John Brown. From my investigations of the man I cannot come to the conclusion that he was a very soft or sympathetic character. In fact, if he were alive today he would be considered direct from Moscow or Germany. I look forward to getting the work finished up because I feel that John Brown panel in particular is one of my greatest works so far.

—John Steuart Curry in a letter to Beth O’Neill

I was very pleased to receive your letter and that you appreciate my conception of John Brown. I think he is the prototype of a great many Kansans. Someone described a Kansan as one who went about wreaking good on humanity. This might be the kernel of my conception. I might also add that I feel our troubles are sufficient for the whole concern. However, this does not seem to be the opinion of a great many Americans, particularly at the present time.

—John Steuart Curry in a letter to Kate Pearson

I wanted to paint him [John Brown] as a fanatic for John Brown was a fanatic. He had the wild zeal of the extremist, the fanatic, for his cause—and we had the Civil War, with its untold misery. My grandfather, for instance died of his wound received in the war. It is the fanatics, the people who insist on going to extremes who cause wars. The cast masses don’t want war—it never brings them any good. What a pity the differences that caused the Civil War were not settled peacefully and amicably. War and beauty do not go together. In the madness and hysteria of war artists are kept busy grinding out horrible atrocity pictures. I studied in Paris—but don’t think we ought to feel it our duty to go to war every time France and other European nations resume their 1,000 year-old quarrels.

— John Steuart Curry describing how his depiction of John Brown expressed his isolationist leanings. “Great Renaissance of Art Seen if United States Escapes War,” The Cincinnati Times-Star, April 10, 1939

His views on art and artists

I wish the farmers of this country would come to some agreement on the style of pigs and cows and horses they’re going to use and then stick to it. When I was a boy they had drag-bellied Poland china pigs, and I learned to draw them that way. Now they still have Poland china pigs but they’ve streamlined them and added legs. And Hereford bulls! See that bull in that picture? That’s the way Hereford bulls looked when I grew up…but one of my farmer friends here took a look at it and said they’re not shaped like THAT any more. Seems to me they change models in live stock as often as they do in Ford cars.”

— John Steuart Curry’s half-joking response to the challenges painters faced highlights his rural roots and his dedication to rendering actualities. “Madison Day by Day,” Wisconsin, April 5, 1939

I don’t feel that I portray the class struggle, but I do try to depict the American farmers’ incessant struggle against the forces of nature. There is no particular political implications in my work either for or against Wall St. I simply attempt to make my American farmlands clear; it not being in my province to portray the class struggle.

— John Steuart Curry explaining that his political beliefs don’t shape his art, “Curry, U.W. ‘Artist In Residence,’ Here; Believes Plan Great Step Forward,”The Capitol, December 4, 1936

My sole interest and conception of subject matter deals with American life, its spirit and its actualities.

— John Steuart Curry in his address to the Art Association of Madison, American Painting, January 19, 1937

I have a great sympathy for the artist and his problems, and particularly for the young artist. In reality it is a single problem; it is the problem of self; the expression of self. When we are young we turn blindly from this light and to that light, seeking the means to express ourselves, borrowing for the time the mannerisms of this master and that master, assuming the cloak of this school or that school. My sincere advice to the young artist is that first he should acquire knowledge, and most important, a knowledge of drawing and structure, learn how the figure is constructed first and be able to paint a solid academic figure, and this need not be a stupid literal performance either. I have had students tiring of this advice burst forth, and as they invariably put it “wish to express themselves”—and invariably they assumed the mannerisms of some one of the masters of the so-called School of Paris, and to those who feel that this is a heavenly transfiguration, let me point out this fact—that these masters in their beginning had an excellent and a more or less thorough training in the academic actualities. This basis has given their adaptations and distortions the authority that their less schooled imitators lack. It is pleasant though to escape the old iron fetters for their golden chains.…From my experience I advise that you sharpen your tools of craft, look behind the flashy and popular contemporary or stylish vogue to their sources, and paint pictures and then more pictures. It takes from five to ten years to develop a competent baseball player or prize fighter. A skilled acrobat goes into training at the age of three and reaches his best at about twenty-four—so in this art of painting you can allow yourself at least ten years of work before you can in your own mind feel the freedom and satisfaction of a controlled craft.

— John Steuart Curry in his address to the Art Association of Madison, American Painting, January 19, 1937

I believe the accurate knowledge of construction and anatomy to be the basis on which to build form. This knowledge gives authority to the creative exaggeration. Sound form construction is based on knowledge of the form and never on what the eye sees.…As to color and composition, I feel a teacher cannot be dogmatic on these two things: he can only advise, as original color and composition are the personal and empiric tights of the artist. Originality of feeling will ride down theory. Students should be directed to study and copy the masters of composition and encouraged to seek out that which will enlarge their powers to translate the life of their own time.…It is the duty of the teacher to excite the student to apply his concrete knowledge to his personal reaction to life. To do this, I feel, demands the greatest discretion and the teacher who places his egotism before the innate feeling of the student does a wrong.

— John Steuart Curry’s essay on the creative process, John Steuart Curry and Curry family papers, 1900–1999. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Box 4, Folder 25

In the minds of many Americans, including critics, painters and esthetes, any American artist is fore-ordained and predestined to damnation. They may have a few patronizing words for the painter who exhibits some mannerism of the popular foreign mode, but that is all; so I say it is a better part to die with the wolves than to be dragged out and slain with the beautiful lambs.

— John Steuart Curry criticizing generic court house decorations that ignore the distinct types of people in a state, Words from Curry, The Wisconsin Country Magazine, February, 1937

Some of us look forward to a great and alive American art. We look forward to a great and alive art in the Middle West, but be reminded of this—the great art is within yourself—within your own heart is the secret of the power that will attract your fellow men. Bring this power forth and with it you bring life to the despised and long-neglected subject. With this power you give a brilliant radiance to the old and hackneyed idea. So I say to you, your greatness will not be found in Europe, nor in New York, nor in the Middle West, nor in Wisconsin, but within yourself, and realize now that for the sincere artist there is no band wagon that goes the whole way, no borrowed coat of perfect fit, and no Jesus on whose breast to lay your curly head.

— John Steuart Curry in his address to the Art Association of Madison, American Painting, January 19, 1937

I wish to point out to you the vastly more difficult problem which we as painters today face than that which faced the Coxes, Blashfields, and the Simmonses of a few years ago. They had no problem of idea. It was a set thing, it was the triumph of the virtues, learning, the law, justice was symbolized by the same well-developed young lady in robes and a nice young man thrown in now and then to nullify the impression that this scene was from the Isle of Lesbos. Because they avoided the realities of life their art form remained static; their only problem was an arrangement of their certain few props, and because they were a close monopoly they had no competition and their work never changed.

Our work today lacks their refined elegance, our line is cruder, the mass more insistent, the prop is unpainted. We have moved with that great part of America that has surged good-naturedly around and past the ballyhooers of the status quo and to the attractions at the other end of the fair ground. The artists of today have the opportunity to use the alive and vital issues as subject matter, and they are doing it. This eagerness to seize on all aspects of American life has given rise to a school classified as the painters of the American scene.

— John Steuart Curry in his address to the Art Association of Madison, American Painting, January 19, 1937

I am not going to try to ‘wreak’ any good on the state. To try to ‘wreak good’ is the quickest way to make people mad. Try to do them good and see where it gets you.

— John Steuart Curry explaining his role as artist in residence hints at his isolationist leanings. “Wisconsin’s Artist in Residence,”Milwaukee Journal, January 10, 1937

After the World War there began a splendid resurgence in art in America and we are in the midst of this movement now—but war will kill it before it can reach its flowering. War and beauty do not go together. In the madness and hysteria of war artists are kept busy grinding out horrible atrocity pictures.

— John Steuart Curry explaining his isolationist leanings. “Great Renaissance of Art Seen if United States Escapes War,”The Cincinnati Times-Star, April 10, 1939

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.