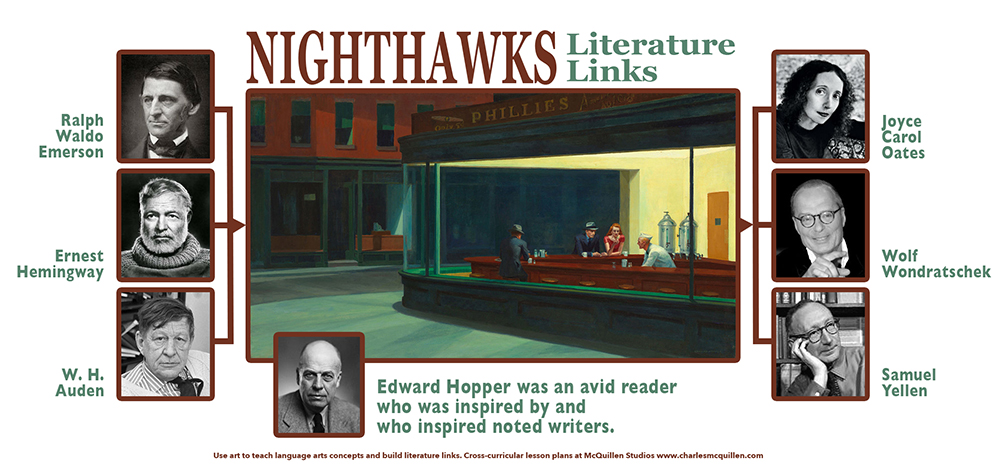

Teach close reading skills, the expressive potential of light, and pregnant spaces with Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks

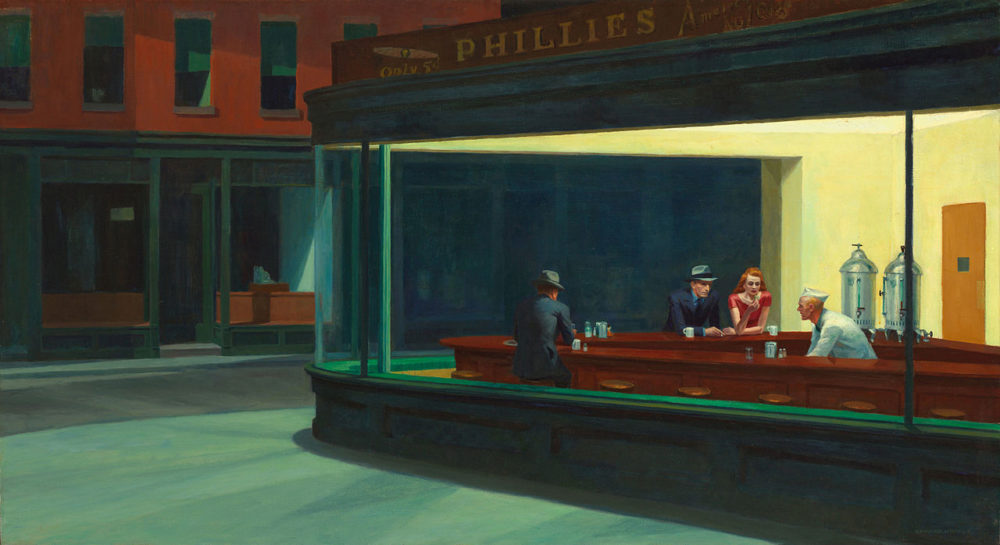

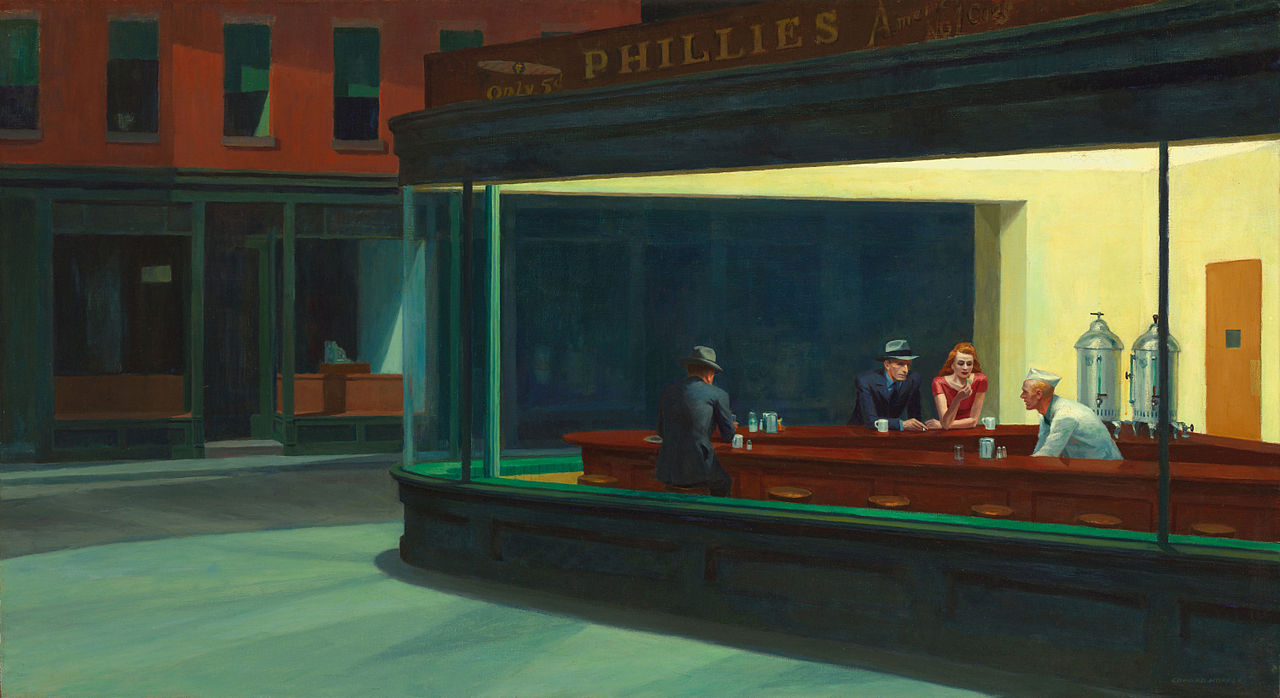

Edward Hoppers Nighthawks is in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago Building. See their website for detailed information. Click on the painting for a high quality image that can be magnified.

Ed refused to take any interest in our very likely prospect of being bombed—and we live right under glass skylights…. He refuses to make for any precautions and only jeers at me for packing a knapsack with towels and keys and soap and check book, shirt, stockings, garters—in case we race out doors in our nighties. For the blackout we have no shade over the skylight…but Ed can’t be bothered. He’s doing a new canvas and simply can’t be interrupted! The Rehn gallery invited E. to remove some of his pictures to a storehouse so that the whole collection won’t be in one place. Frank Rehn is very concerned and making many precautionary measures. I can’t say I’m a bit panicy but I’m the kind that believes in precautions, and in a matter that everyone is concerned in, I can’t see why anyone refuses to take an interest. Hitler has said that he intends to destroy New York and Washington… It takes over a month for E. to finish a canvas and this one is only just begun…E. doesn’t want me even in the studio. I haven’t gone thru even for things I want in the kitchen.

—Josephine Hopper in a letter to her sister-in-law Marion Hopper (December17, 1941, 10 days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor) describing the focus her husband, Edward Hopper, brings to his work as he begins to paint Nighthawks

Ed has just finished a very fine picture—a lunch counter at night with 3 figures. Night Hawks would be a fine name for it. E. posed for the 2 men in a mirror and I for the girl. He has about a month and half working on it—interested all the time, too busy to get excited over public outrages. So we stay out of fights.

—Josephine Hopper in a letter to Marion Hopper (January 22, 1942)

Nighthawks seems to be the way I think of a night street. I didn’t see it as particularly lonely. I simplified the scene a great deal and made the restaurant bigger. Unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.

—Edward Hopper responding to Katherine Kuh’s question about the loneliness in the picture. (The Artist’s Voice ©1962, page 134)

Look at Nighthawks. Before reading the excerpts above, tell students the title of the piece and ask what is going on in this picture? Edward Hopper provides lots of clues but requires the viewer to put them all together and finish the narrative. Encourage students to identify the evidence that supports the reasoning behind their interpretations. Note the emotional states students attribute to the characters as this may inform discussions to come. Students should likewise be encouraged to share wonderings and voice confusions. As the conversation slows, explain you are going to read excerpts about the painting’s backstory. After reading the excerpts ask how does this new insight change your understanding of the painting?

Begin with art history

During the summer of 1882 Edward Hopper was born into a well-educated family in Nyack, New York. While his parents supported his artistic pursuits, they encouraged him to pursue the commercial arts for a source of steady income. After studying art in New York and Paris, he split his time between his own painting and drawing and working as a magazine and movie poster illustrator. It wasn’t until he was 41 that he achieved financial security selling his own work. Early on these were watercolor portraits of seacoast scenes and, in time, the oil paintings he is best known for.

Socially and politically conservative, Hopper was defiantly individualistic. He lived a reclusive lifestyle and found comfort in quiet routines and solitude. He was an introvert who incorporated long hours of seclusion into his creative process. When he wasn’t traveling the back roads of rural Cape Cod and walking the street of New York City looking for subjects to paint, he buried himself in reading. One of his favorite writers was Ralph Waldo Emerson, an essayist who celebrated “the infinitude of the private man” and warned against the tyranny of the masses. Hopper suffered from bouts of melancholy when he struggled to find subjects to paint.

Hopper’s art reflected his introspective personality. He felt that great art was the outward expression of the artist’s inner life and worldview. In explaining his creative process, Hopper describes how he used life sketches to establish a visual understanding and then relied on his subconscious to refine the final composition of his paintings.

The picture was planned very carefully in my mind before starting it, but except for a few small black and white sketches made from the fact, I had no other concrete data, but relied on refreshing my memory by looking often at the subject.…The color, design, and form have all been subjected, consciously or otherwise to considerable simplification. So much of every art is an expression of the subconscious, that it seems to me most all of the important qualities are put there unconsciously, and little of importance by the conscious intellect.

Building on his personal worldview, Hopper created his own unique style of “soft” realism that methodically distilled essential elements into composite arrangements that looked specific, but evoked the universal. While many attributed symbolic or psychological significance to his work, Hopper strove to accurately depict an impression of nature as he experienced it in his mind’s eye. Unlike many of the Depression era artists, Hopper’s work didn’t moralize or delve into social issues. Instead, he focused the convergence of natural elements that inspired him personally, oftentimes exploring the expressive potential of light. Through his deft handling of natural and man-made light, and its requisite shadows, Hopper made silent spaces poignant and heightened the drama in uneasy encounters.

Look like an art critic

This image from the Art Institute of Chicago Building lets you magnify the painting and see exquisite detail. Thank you Art Institute of Chicago!

What’s in a name? —The importance of a title

Point out and discuss: Consider the etymological differences between the term nighthawks versus night owls.

Night owl is term derived from the nocturnal habits of the owl and is associated with people who habitually stay up late at night, or work night shifts. A night owl is a type of person. There are different types of owls, but no actual bird is called a night owl.

Nighthawks are a bird of prey that feeds on flying insects at dusk. They are sometimes referred to as goatsuckers from the mistaken belief that they suck milk from goats. In trafficking circles, the term nighthawk refers to thieves who loot archaeological sites at night and then sell the stolen antiquities on the black market.

How might the differences between these similar terms inform the interpretation of the painting?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: While owls and hawks are both birds of prey the owl is oftentimes connoted with wisdom, while hawks are recognized as attacking predators. The nighthawk associating makes the people more animalistic. The animal association makes you reflect on the beak-like nose of the man with the woman. The reference to hawks seems more sinister, which makes the enveloping darkness more menacing. If Night Owls was the title of a movie it sounds like a comedy about late shift workers. Nighthawks sounds like a dark whodunit mystery movie. The mysterious nature of the Nighthawk title lends itself to viewer speculation and interpretation. The sinister reading of the title makes you wonder what the people have to hide.)

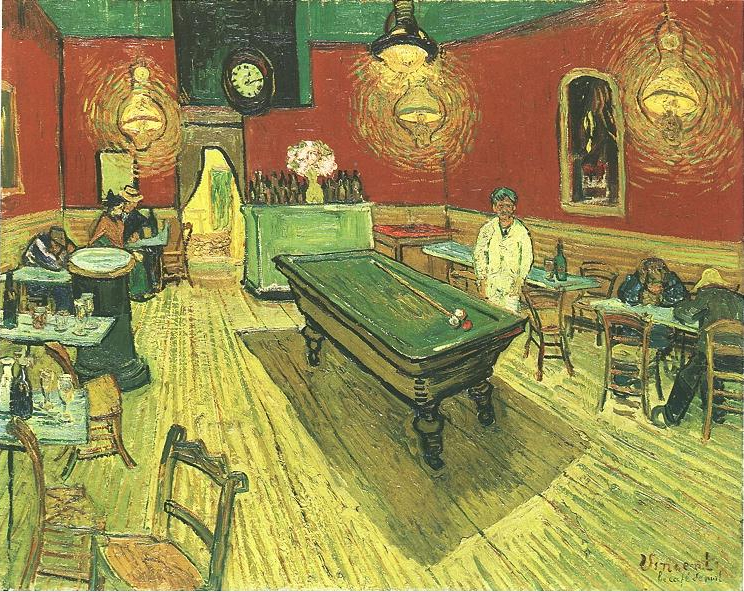

Compare Vincent van Gogh’s The Night Café with Hopper’s Nighthawks

In a series of letters to his brother Theo, Vincent van Gogh described his intentions in painting The Night Café (1888).

Today I am probably going to begin on the interior of the café where I have a room, by gas light, in the evening. It is what they call here a “café de nuit” (they are fairly frequent here), staying open all night. “Night prowlers” can take refuge there when they have no money to pay for a lodging, or are too drunk to be taken in.…

I have tried to express the terrible passions of humanity by means of red and green. The room is blood red and dark yellow with a green billiard table in the middle; there are four lemon-yellow lamps with a glow of orange and green. Everywhere there is a clash and contrast of the most alien reds and greens, in the figures of little sleeping hooligans, in the empty dreary room, in violet and blue. The blood-red and the yellow-green of the billiard table, for instance, contrast with the soft tender Louis XV green of the counter, on which there is a rose nosegay.…

In my picture of the Night Café I have tried to express the idea that the café is a place where one can ruin oneself, go mad or commit a crime. So I have tried to express, as it were, the powers of darkness in a low public house, by soft Louis XV green and malachite, contrasting with yellow-green and harsh blue-greens, and all this in an atmosphere like a devil’s furnace of pale sulphur.…It is color not locally true from the point of view of the stereoscopic realist, but color to suggest the emotion of an ardent temperament.…

Point out and discuss: Van Gogh’s Night Café was one of Hopper’s favorite paintings. Compare Night Café with Nighthawks. What traits do these paintings share? How are Hopper’s intentions similar to van Gogh’s?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: Both artists are focusing on the inhabitants of all-night haunts and the challenge of rendering a new form of man-made light—gas lights for van Gogh and incandescent lights for Hopper. Both artists also apply the same color theory to create dreary discordant environments that evoke the darker side of human nature. Both paintings use red and green complimentary colors to create an unstable oppressive environment. Both artists create green tinted shadows in the foreground. Darker green elements unite the composition—the pool table, ceiling, and tabletops in The Night Café and window frames and shades in Nighthawks. Blood red walls and a cherry counter serve as a backdrop that stretches across each canvas. Since cool colors (greens) visually recede and warm colors (reds) visually project forward, this strategic juxtaposition creates a disorienting jittery surface. The garish light in both paintings evoke “a devil’s furnace of pale sulphur.” The wayward night prowlers in both paintings are hunched and spent, lost in their thoughts and fatigue. Both van Gogh and Hopper explore the unsettling power of darkness and offer a study in loneliness and despair. Painted just days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, does Nighthawks reflect Hopper’s subconscious anxieties about the impending war?)

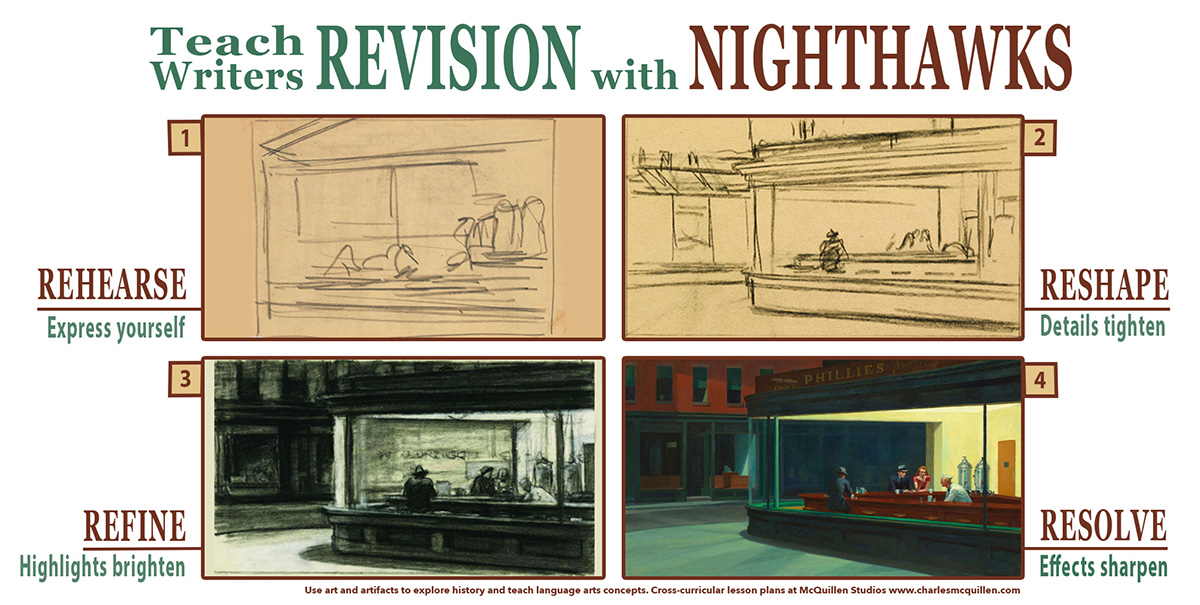

Compare preliminary sketches with the final painting

The idea had been in my mind a long time before I painted it. It was suggested by a glimpse of lighted interiors seen as I walked along the city streets at night, probably near the district where I live although it’s no particular street or house, but is really a synthesis of many impressions.

— Edward Hopper

Point out and discuss: This description of how Hopper painted Room in New York (1932) is indicative of his creative process. He used quick sketches to catch fleeting observations. Through a series of sketches he zeroed in on a composition that fittingly evoked the intangible feeling or mood he hoped to capture. Analyze the progression of the three preliminary sketches. Note especially how the light, space, and figures are composed. How does this visual progression serve Hopper’s intentions in his final painting?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers:

- Sketch 1 is rough but suggests the coffee urns and the people. The interior of the diner is balanced and consumes the composition. The horizontal lines of the counter and window are shown. The grouping of the figures is very intimate and compact.

- Sketch 2 draws back with a third of the composition now revealing the street around the diner. The space is bigger and figures are smaller and more distant. The composition is increasingly imbalanced. While the couple remains compact the single man grows more isolated. More details, such as the stools and window frames, are shown and the beginnings of shadows appear on the street.

- Sketch 3 shows distinct architectural features and light sources. The surrounding darkness heightens the imbalance of the composition. Chalk is used to show the light that spills out onto the street. The couple is shown as distinct figures. They turn toward and lean into each other. The man behind the counter looks down as if working with something.

- In the painting the figures are slighter and more distinct. Note the space that now separates the couple. The couple sits straight up and looks away from each other. The figure behind the counter looks up but past his customers. Minor implements and personal details are shown. The interior of the diner is more spacious. The painting now shows a sliver of ceiling and the back wall is bigger showing space around the door, adding more light to the scene. The light from the diner creates angular patterns on the street beyond.

The evolution of the composition emphasizes psychological isolation and introspection. The drawings focus on factual external relationships, while the painting emphasizes inner psychological feelings. Subtle shifts in gesture and placement show how Hopper improvised, honing in on his instinct and the feeling or mood he was striving for. As the space grows in scale, the figures become more remote and emotionally detached. The pregnant space between the couple introduces ambiguity and opens the door for alternative narratives. The composition’s growing imbalance creates a visual tension that instills a sense of unease. The dichotomy between the lighted interior of the diner and the dark street is echoed in the figures. The motionless diner inhabitants stand in contrast to the roiling introspection that is evidenced in their distant stares.)

Think Like an Artist

While some see welcome solitude and others see lonely alienation, Hopper’s art reflected a distinct perspective and style. Hopper’s far-ranging subjects are oftentimes unified by a deft treatment of light. In these paintings, sunlight and artificial light serve as practical compositional elements, psychological metaphors, and even as subjects.

Consider the expressive treatment of light in the gallery above. Click on an image to enlarge. Access the embedded text links to high resolution images. These images are drawn from across Hopper’s career. Automat,1927; Room in Brooklyn, 1932; New York Movie, 1939; Gas, 1940; Summer Evening, 1947; Morning Sun, 1952; Second Story Sunlight, 1960; Sun in an Empty Room, 1963. Sun in an Empty Room was one of Hopper’s last paintings. Fittingly, soft shimmering late-day sunlight illuminates an empty, or recently vacated room.

Use your cell phone’s camera to capture the expressive potential of light in your life. Carefully consider your photograph’s composition and what is shown within the confines of the frame. From a series of images, select your favorite. What is it about this image that distinguishes it from the others. Show your image to your classmates and note shared themes.

Life Lesson

Originality and creativity are compost?

Most of my paintings are composites—not taken from one scene.…I make preliminary drawings of different sections—then combine them. My watercolors are all done from nature—direct—out-of-doors and not made as sketches. I do very few these days; I prefer working in my studio. More of me comes out when I improvise. You see, the watercolors are quite factual. From the oils I eliminate more.…Maybe there is such a thing as inspiration. Maybe it’s the culmination of a thought process. But it’s hard for me to decide what I want to paint. I go for months without finding it sometimes. It comes slowly, takes form; then inventions come in.…I find I get more of myself by working in the studio.…I don’t think I ever tried to paint the American scene; I’m trying to paint myself.

—Edward Hopper, thoughts from an interview with Katherine Kuh (The Artist’s Voice ©1962)

One of Hopper’s most influential teachers, Robert Henri, encouraged him to wander the city looking for subjects and sketching the details he happened upon. Increasingly, this became Hopper’s practice as he formulated compositions. His creative process was a mix of drawing from nature and improvising in his studio from impressionistic images. This made his art both specific and universal. In any creative endeavor be receptive, absorb all you can, draw from a spectrum of sources, sketch what interests you, mix it all together, and find the universal in yourself.

Related Video and Multimedia Resources

- The Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Edward Hopper Scrapbook offers an innovative way to explore Hopper’s life, paintings, and related writings.

- National Public Radio’s Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks presents a series of radio interviews and reports related to this iconic painting.

- In Sunday Morning’s The American simplicity of Edward Hopper (8:34) Morley Safer discusses Hopper’s characteristic style and themes as he tours the Edward Hopper exhibit at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

- In Smarthistory’s Hopper, Nighthawks (4:47) Dr. Beth Harris & Dr. Steven Zucker provide a scholarly analysis of Nighthawk’s history, elements, principles of design.

- Edward Hopper’s Creative Process (2:04) overlays an interview with Hopper with related sketches and paintings to explore his creative motivations and process.

- Nerdwriter’s Hopper’s Nighthawks: Look Through the Window (7:38) uses Nighthawks as a case study to explore the themes in Edward Hopper’s work.

- In Edward Hopper – Painter of alienation (53:10) Colin Wingfeld views Hopper’s painting through Eric Fromm’s psychoanalytic lens. While Hopper likely would have felt that this lens is distortedly myopic, this in-depth analysis is sophisticated and revealing, highlighting subtle ways to visually depict psychological alienation. The analysis of Nighthawks begins at minute 46.

Integrating into Your Curriculum

Artists oftentimes use common visual strategies or signposts to alert viewers to significant details in their art. Here are some ideas for using these visual signposts to unpack a work of art. Remember, the close reading skills in art appreciation are similar to the close reading practices taught in reading.

Literature Links: What piece of literature would you partner with Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks? Nighthawks offers a number of avenues for literary exploration. Hopper was an especially avid reader. First consider a chain of inspiration and influence.

Literature Links: What piece of literature would you partner with Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks? Nighthawks offers a number of avenues for literary exploration. Hopper was an especially avid reader. First consider a chain of inspiration and influence.

- Ralph Waldo Emerson was one of Hopper’s favorite authors and his essay “Self Reliance” was singled out for its incomparable clarity and its advocacy for a unique form of American self-expression. This essay promotes a brand of defiant individualism that Hopper identified with and that informed his art and his politics. Read this with Hopper’s Notes on Painting (1933) and note the Emersonian influence. Notes on Painting is provided below in the quotes section and is discussed in a 1959 Smithsonian interview.

I admire him [Emerson] greatly. I read him quite a lot. I read him over and over again.

- Hopper biographer Gail Levin contends that Nighthawks may have in part been inspired by Ernest Hemingway’s short story The Killers (1927). A spare, dialogue-rich short story, The Killers tells the tale of two thugs who enter a diner in search of their next victim Ole Andreson, a regular customer and boxer who has run afoul of a ruthless criminal element. In response to the publication of the short story in Scribner’s Magazine, Hopper wrote a letter to the editor that reflected his own artistic sensibility.

I want to compliment you for printing Ernest Hemingway’s “The Killers” in the March Scribner’s. It is refreshing to come upon such an honest piece of work in an American magazine, after wading through the vast sea of sugar-coated mush that makes up the most of our fiction. Of all the concessions to popular prejudices, the side stepping of truth, and of the trick ending there is no taint in this story.

- Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946), (trailer here) starring Burt Lancaster, Ava Gardner, and William Conrad (Cannon) is a classic film noir based on Hemingway’s short story and may have found visual inspiration from Nighthawks. Compare the first six minutes of the movie with the short story and the painting.

- Ernest Hemingway’s short story A Clean Well-Lighted Place (1933) is an existential short story that has philosophical and physical ties to Hopper’s late-night diner.

Another equally interesting avenue of literary exploration considers Edward Hopper’s literary peers as they observe and critique American urban spaces, exploring themes of nonconformity, social constraints, and psychological alienation.

- H. Auden’s poem September 1, 1939 (1939) shares (possibly inspires) Nighthawks imagery and expresses the overwhelming despair from a decade of grinding economic depression and the imminent outbreak of World War II. The poem concludes with a glimmer of hope for the future.

- Dashiell Hammett’s hard boiled detective novels such as The Glass Key (1931) and The Maltese Falcon (1930) evoke the self-reliance and cynical detached sensibility of Hopper’s Nighthawks (not to mention settings and fashion) and the voyeuristic spying from the shadows of the viewer.

- John Dos Passos’ Manhattan Transfer (1925) profiles the lives of New Yorkers at the turn of the 20th century honing in on their unrequited love, disintegrating relationships, broken dreams, and creeping desperation.

- Scott Fitzgerald’s The Beautiful and the Damned (1922) chronicles the aimless and self-absorbed lives of a couple from New York’s café society.

Writing Opportunity: Creative fiction writing and dialogue. Hopper’s Nighthawks may have in part been inspired by Hemingway’s short story The Killers. In turn Nighthawks has inspired short stories and poetry.

- Joyce Carol Oates’ poem Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks, 1942 presents the tortured internal monologues of the couple in the painting as they reflect on their dysfunctional relationship.

- Wolf Wondratschek’s poem Nighthawks: After Edward Hopper’s Painting likewise explores the growing alienation that consumes the customers of the late-night diner.

- Samuel Yellen’s Nighthawks (1952) reflects on the emotional abyss between the inhabitants at the “corner of Empty and Bleak,” at the night’s most desolate hour.

- Michael Connolly’s iconic private detective Hieronymus Bosch meets the Nighthawk characters as he surveils a woman of interest in this 1000 word short story.

- D. Jackson wrote a science fiction short story where the Nighthawk couple are time-traveling aliens (?) that warn of the 9/11 attack. (Ignore the fact that the painting was created 30 years before the World Trade Center was built. Time travel can do that.)

As Jackson explains in his post “They say a picture is worth a thousand words. Well, here are my nearly thousand words inspired by Hopper’s masterpiece.” These are interesting parameters for a writing assignment. Using these writings as a model, have students write their own dialogue-rich work of fiction based on the characters in the painting. For additional ideas, infrastructure, and tools see a related lesson at Tim’s Free English Lesson Plans.

How would you use this painting to build on one of your units of study? Please share if you have other ideas on how to teach Nighthawks by Edward Hopper as an English/language arts lesson plan.

Click this link to see how Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks can be used to teach writers the revision process.

Description of Nighthawks

Night + brilliant interior of cheap restaurant. Bright items: cherry wood counter + tops of surrounding stools; light on metal tanks at rear right; brilliant streak of jade green tiles 3/4 across canvas–at base of glass of window curving at corner. Light walls, dull yellow ocre [sic] door into kitchen right. Very good looking blond boy in white (coat, cap) inside counter. Girl in red blouse, brown hair eating sandwich. Man night hawk (beak) in dark suit, steel grey hat, black band, blue shirt (clean) holding cigarette. Other figure dark sinister back–at left. Light side walk outside pale greenish. Darkish red brick houses opposite. Sign across top of restaurant, dark–Phillies 5c cigar. Picture of cigar. Outside of shop dark, green. Note: bit of bright ceiling inside shop against dark of outside street–at edge of stretch of top of window.

—Jo Hopper’s physical description of Nighthawks in a painting ledger of Edward Hopper’s work.

Hoppers views on art

My aim in painting has always been the most exact transcription possible of my most intimate impressions of nature. If this end is unattainable, so, it can be said, is perfection in any other ideal of painting or in any other of man’s activities. The trend in some of the contemporary movements in art, but by no means all, seems to deny this ideal and to me appears to lead to a purely decorative conception of painting. One must perhaps qualify this statement and say that seemingly opposite tendencies each contain some modicum of the other. I have tried to present my sensations in what is the most congenial and impressive form possible to me. The technical obstacles of painting perhaps dictate this form. It derives also from the limitations of personality, and such may be the simplifications that I have attempted. I find in working always the disturbing intrusion of elements not a part of my most interested vision, and the inevitable obliteration and replacement of this vision by the work itself as it proceeds. The struggle to prevent this decay is, I think, the common lot of all painters to whom the invention of arbitrary forms has lesser interest. I believe that the great painters with their intellect as master have attempted to force this unwilling medium of paint and canvas into a record of their emotions. I find any digression from this large aim leads me to boredom. The question of the value of nationality in art is perhaps unsolvable. In general it can be said that a nation’s art is greatest when it most reflects the character of its people. French art seems to prove this. The Romans were not an aesthetically sensitive people, nor did Greece’s intellectual domination over them destroy their racial character, but who is to say that they might not have produced a more original and vital art without this domination. One might draw a not too far-fetched parallel between France and our land. The domination of France in the plastic arts has been almost complete for the last thirty years or more in this country. If an apprenticeship to a master has been necessary, I think we have served it. Any further relation of such a character can only mean humiliation to us. After all, we are not French and never can be, and any attempt to be so is to deny our inheritance and to try to impose upon ourselves a character that can be nothing but a veneer upon the surface. In its most limited sense, modern, art would seem to concern itself only with the technical innovations of the period. In its larger, and to me irrevocable, sense, it is the art of all time of definite personalities that remain forever modern by the fundamental truth that is in them. It makes Moliere at his greatest as new as Ibsen or Giotto as modern as Cezanne. Just what technical discoveries can do to assist interpretative power is not clear. It is true that the Impressionists perhaps gave a more faithful representation of nature through their discoveries in out-of-door painting. But that they increased their statute as artists by so doing is controversial. It might here be noted that Thomas Eakins in the nineteenth century used the methods of the seventeenth, and is one of the few painters of the last generation to be accepted by contemporary thought in this country. If the technical innovations of the Impressionists led merely to a more accurate representation of nature, it was perhaps of not much value in enlarging their powers of expression. There may come, or perhaps has come, a time when no further progress in truthful representation is possible. There are those who say that such a point has been reached, an attempt to substitute a more and more simplified and decorative calligraphy. This direction is sterile and without hope to those who wish to give painting a richer and more human meaning and a wider scope. No one can correctly forecast the direction that painting will take in the next few years, but to me at least there seems to be a revulsion against the invention of arbitrary and stylized design. There will be, I think, an attempt to grasp again the surprise and accidents of nature and a more intimate and sympathetic study of its moods, together with a renewed wonder and humility on the part of such as are still capable of these basic reactions

—Notes on Painting (1933) was written for his first retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. See also the discussion about this essay in a 1959 Smithsonian interview

Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist, and this inner life will result in his personal vision of the world. No amount of skillful invention can replace the essential element of imagination. One of the weaknesses of much abstract painting is the attempt to substitute the inventions of the intellect for a pristine imaginative conception. The inner life of a human being is a vast and varied realm and does not concern itself alone with stimulating arrangements of color, form, and design. The term “life” as used in art is something not to be held in contempt, for it implies all of existence, and the province of art is to react to it and not to shun it. Painting will have to deal more fully and less obliquely with life and nature’s phenomena before it can again become great.

So much of every art is an expression of the subconscious, that it seems to me most all of the important qualities are put there unconsciously, and little of importance by the conscious intellect. But these are things for the psychologist to untangle.

Most of my paintings are composites—not taken from one scene.…I make preliminary drawings of different sections—then combine them. My watercolors are all done from nature—direct—out-of-doors and not made as sketches. I do very few these days; I prefer working in my studio. More of me comes out when I improvise. You see, the watercolors are quite factual. From the oils I eliminate more.…I find I get more of myself by working in the studio.…I don’t think I ever tried to paint the American scene; I’m trying to paint myself.

—in an interview with Katherine Kuh (The Artist’s Voice ©1962, page 135)

Well, maybe there is such a thing as inspiration. Maybe it’s the culmination of a thought process. But it’s hard for me to decide what I want to paint. I go for months without finding it sometimes. It comes slowly, takes form; then inventions come in. Unfortunately, I think so many paintings are purely invention—nothing comes from inside. You have to use invention, of course; nothing comes out without it. But there’s a difference between invention and what comes from inside a painter.…I paint only for myself. I would like my work to communicate, but if it doesn’t, that’s all right too. I never think of the public when I paint—never.

—in an interview with Katherine Kuh (The Artist’s Voice ©1962, page 141)

In Art school you paint the figure because the model is there to work from. Afterward you’re free to do what you want. Maybe I include figures sometimes because I feel it’s a duty to “do” humanity. Though I studies with Robert Henri I was never a member of the Ash-Can School. You see, it had a sociological trend which didn’t interest me.

—in an interview with Katherine Kuh (The Artist’s Voice ©1962, page 140)

The idea [for his painting Room in New York] had been in my mind a long time before I painted it. It was suggested by glimpses of lighted interiors seen as I walked along city streets at night, probably near the district where I live although it’s no particular street or house, but is really a synthesis of many impressions.

Originality is neither a matter of inventiveness nor method, it is the essence of personality.

I do not know why I chose one subject rather than another unless I believe them to be the best synthesis of my inner experience.

All I ever wanted to do is to paint sunlight on the side of a wall.

The only quality that endures in art is a personal vision of the world. Methods are transient: personality is enduring.

I wish I could paint more. I do dozens of sketches for oils. if I do one that interests me I go on to make a painting but that happens only two or three times a year.

[Jo, his wife, remarked on Hopper’s painting ‘Cape Cod morning’, 1950: ‘It is a woman looking out to see if the weather is good enough to hang out her wash’. Edward Hopper reacted:] ‘did I say that? You’re making it Norman Rockwell. From my point of view she’s just looking out the window, just looking out the window’.

His view on World War II

In a letter to his friend Guy Pène du Bois, Hopper presents a revealing view of the war.

We are evidently eye witnesses to one of those great shiftings of power that have occurred periodically in Europe, as long as there has been a Europe, and there is not much to be done about it, except to suffer the anxiety of those on the side lines, and to try not to be shifted ourselves.

It seems that I have no definite philosophy that would be a consolation in these times, but if I had one, it would be of no use to you, for you would not like it and no doubt would despise it. Jo seems to be no better off than I am for philosophy, for she burst into tears among all the groceries in a store here in Wellfleet when she heard of the fall of Paris, and was patted and consoled by the grocer’s wife, who I feel sure was much puzzled to know why anybody should actually weep over something happening so far away from Wellfleet.

Painting seems to be a good enough refuge from all this, if one can get one’s dispersed mind together long enough to concentrate upon it.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.