Teach close reading skills, allegory, and the importance of wildlife conservation with Albert Bierstadt’s The Last of the Buffalo.

Related Resources

- Albert Bierstadt’s The Last of the Buffalo is in the National Gallery of Art’s collection. See their website for detailed information. Select the image to magnify.

- This interactive puzzle explores Bierstadt’s life and the art and events that inspired him to paint The Last of the Buffalo. Special attention is given to the near extinction of the buffalo and its impact on Native American cultures.

- This team-building game reviews key learnings from “Puzzled by The Last of the Buffalo?”

- This sorting activity explores the distinct styles of art of four influential American artists from the mid 1800s — Albert Bierstadt, Eastman Johnson, Emanuel Leutze, and Worthington Whittredge.

- This game-based art survey analyzes the art of Albert Bierstadt and eight other 19th century landscape painters.

- This inquiry study uses The Last of the Buffalo as a springboard to explore wildlife conservation and the value of national parks.

It is a matter of indifference to me but I cannot understand why you refuse my picture, for there is only one, The Last of the Buffalo…They were the jury appointed to select works of art by resident American artists for the Paris Exposition. In their circular they say this is the first opportunity to display in Europe the art of this country since 1878, and give utterance to the belief that American art has made great advance during the past ten years, which is undoubtedly true. All works produced by an American citizen since 1878 were to be eligible, and artists were urged to send their best work.

I was, of course, anxious to aid the art jury, and designated The Last of the Buffalo because it was one of my latest and was considered by my friends and competent critics as among my best efforts. Since then I have heard nothing more about the matter until I read the cable dispatch in today’s World. The picture is now in the Paris Salon, and I hear it has been given an exceedingly good place. Of course, if the American Art Committee doesn’t want my picture it must remain in the Salon. I am, of course, sorry that there has been any trouble, for it is an unpleasant episode; but as my picture has been accepted by the Salon my countrymen visiting the Exposition can see it there. I wish it distinctly understood that I have no feeling in the matter, only that it is unpleasant. Why my picture was rejected I, of course, do not know.

I have endeavored to show the buffalo in all his aspects and depict the cruel slaughter of a noble animal now almost extinct. The buffalo is an ugly brute to paint, but I consider my picture one of my very best.

—Albert Bierstadt in an interview with the World (March 1889) questioning why his painting The Last of the Buffalo was excluded from the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle

I wish these lines could find Mr. Bierstadt somewhere. He is a very great man here now, and enjoying a huge Indian celebrity that he does not thoroughly appreciate. His Salon picture, The Last of the Buffalo, has been seen thrice by Rocky Bear.…[As Rocky Bear] motions his brethren around him and in the Bierstadt inspiration tells them how they have taken the “hand of the white man and his whisky and sold their plains, where the buffalo was wont to run wild as in this splendid picture.” Rocky Bear is eloquent in the Indian language, and he is long; but the mute and silent red faces…sit mum and smoke the pipe of peace,…tomorrow they will come again, and when Rocky Bear goes home he says he is going to see Bierstadt and make all the children of the tribe look upon the great man who has given breath and life to the glorious past of the redskin and the buffalo, when the Indian was the master of all he could survey, and he then surveyed a large tract. Our artist is undoubtedly accustomed to success, and the poor Indian’s tribute of admiration is a modest one; yet it is pleasant to learn that these men of the plains leave their tents in the Cody camp each morning to come and breathe the air—as they put it—of their native soil; and their grunt of satisfaction after a silent half hour on contemplation should be a joy to the painter’s soul, for it is a recognition of the truth of the scene, and is eloquent to its sentiment and poetry.

—A New York Times article by L.K. (October 1, 1889) describing how Rocky Bear and other Sioux Chiefs touring with “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s Wild West Show in Paris, France visited the Paris Salon daily to view Albert Bierstadt’s painting The Last of the Buffalo.

Look at The Last of the Buffalo. Before reading the excerpts above, tell students the title of the piece and ask what is going on in this picture? Encourage students to identify the evidence that supports the reasoning behind their interpretations. Albert Bierstadt’s style is very realistic and detailed. Encourage students to note these details as they will inform the discussions to come. Students should likewise be encouraged to share wonderings and voice confusions. As the conversation slows, explain you are going to read two newspaper accounts on the painting’s initial reception—one, about the painting’s rejection from a prestigious Paris art exhibition and, the other, a more favorable response by Sioux Chiefs from Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show that was visiting Paris at the time. After reading the excerpts ask how does this new insight change your understanding of the painting?

Note: This painting offers an opportunity for fun with homonyms (words having the same spelling but different meanings) and homophones (words that sound alike but have different meanings). Explain that the word buffalo can have three distinct meanings.

- Noun adjunct: Buffalo is a city in upstate New York that can be used as a noun or a descriptor

- Noun: buffalo is an animal (American bison)

- Verb: to buffalo means to outwit, intimidate, and deceive

Challenge your students to explain these grammatically correct sentences (capitalization is key):

- Buffalo Buffalo buffalo! (This is a command to intimidate bison from Buffalo.)

- Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo. (Bison from Buffalo intimidate other bison.)

- Buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo. (Bison from Buffalo intimidate other bison from Buffalo.)

How far can you take this? Here is a sophisticated reading that uses eight buffalo in one grammatically correct statement.

- Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo

This sentence claims that bison that are bullied by bison are themselves bullying bison in Buffalo. See Wikipedia for a complete explanation.

Begin with art history

Albert Bierstadt was born in Germany January 7, 1830. While still a toddler he moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts with his parents and five siblings. In 1853 he returned to Germany to study art in the Düsseldorf school of painting, a group of influential art teachers who emphasized theatrical compositions, hard-edged Neoclassical drawing techniques, careful attention to detail, and romanticized landscapes. Sentimental, fanciful, and allegorical in content, these paintings tended to be painstakingly executed in a highly finished style.

After four years of study and the painting of Europe’s majestic mountains, Bierstadt returned to New Bedford to establish a studio and his reputation. In 1859 Bierstadt joined a government expedition to survey and remap the Overland Trail. Bierstadt described this grand adventure into America’s wilds in a letter to The Crayon (offered in its entirety in the highlighted section below). He returned to his studio in 1860 loaded with sketchbooks and photographs, Native American artifacts, and a passion for the American West. In the years to come he would make two more western expeditions including trips to Yosemite Valley where he found his greatest inspiration.

Bierstadt was as much a showman and entrepreneur as he was a painter. He emphasized spectacular effects over accurate details. The content and scale of his panoramic landscapes were crafted to induce wonder and awe. A shameless self-promoter, Bierstadt introduced his newest paintings in carnival-like events with theatrically lit rooms and paid admittance. The combination of painting and promotion made Bierstadt a celebrity in the United States and Europe and one of the most lucrative artists of the 1860s and 70s.

By the time he painted The Last of the Buffalo in 1888 his popularity had significantly declined and critics had become more vocal. His oversized canvasses were condemned as self-indulgent, his effects as excessive, and his compositions formulaic. Bierstadt’s academic style was seen as old fashioned as Impressionism rose to prominence in the art world. Consider that The Last of the Buffalo was painted at the same time Vincent van Gogh was painting The Starry Night. While The Last of the Buffalo was initially rejected, today it is celebrated at one of Bierstadt’s most significant paintings. Bierstadt witnessed the transformation of the American West, and while his work reflected Manifest Destiny ideals, this painting evokes contemporary issues of his and our times—wildlife conservation and preservation, species displacement, and the related destruction of indigenous cultures.

Of course the slaughter was greatest along the lines of the three great railways—the Kansas Pacific, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fé, and the Union Pacific, about in the order named. It reached its height in the season of 1873. During that year the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fé Railroad carried out of the buffalo country 251,443 robes, 1,017,600 pounds of meat, and 2,743,100 pounds of bones. The end of the southern herd was then near at hand. Could the southern buffalo range have been roofed over at that time it would have made one vast charnel-house. Putrifying carcasses, many of them with the hide still on, lay thickly scattered over thousands of square miles of the level prairie, poisoning the air and water and offending the sight.

— William T. Hornaday describing the carnage of the vast buffalo herds that took their numbers from tens of millions to only a few dozen in a couple of decades. See his influential The Extermination of the American Bison. During his expeditions into the West, Bierstadt witnessed, and even participated in, this slaughter.

Look like an art critic

This image from the National Gallery of Art lets you magnify the painting and see exquisite detail. Thank you National Gallery of Art!

Describe Bierstadt’s unique style of art

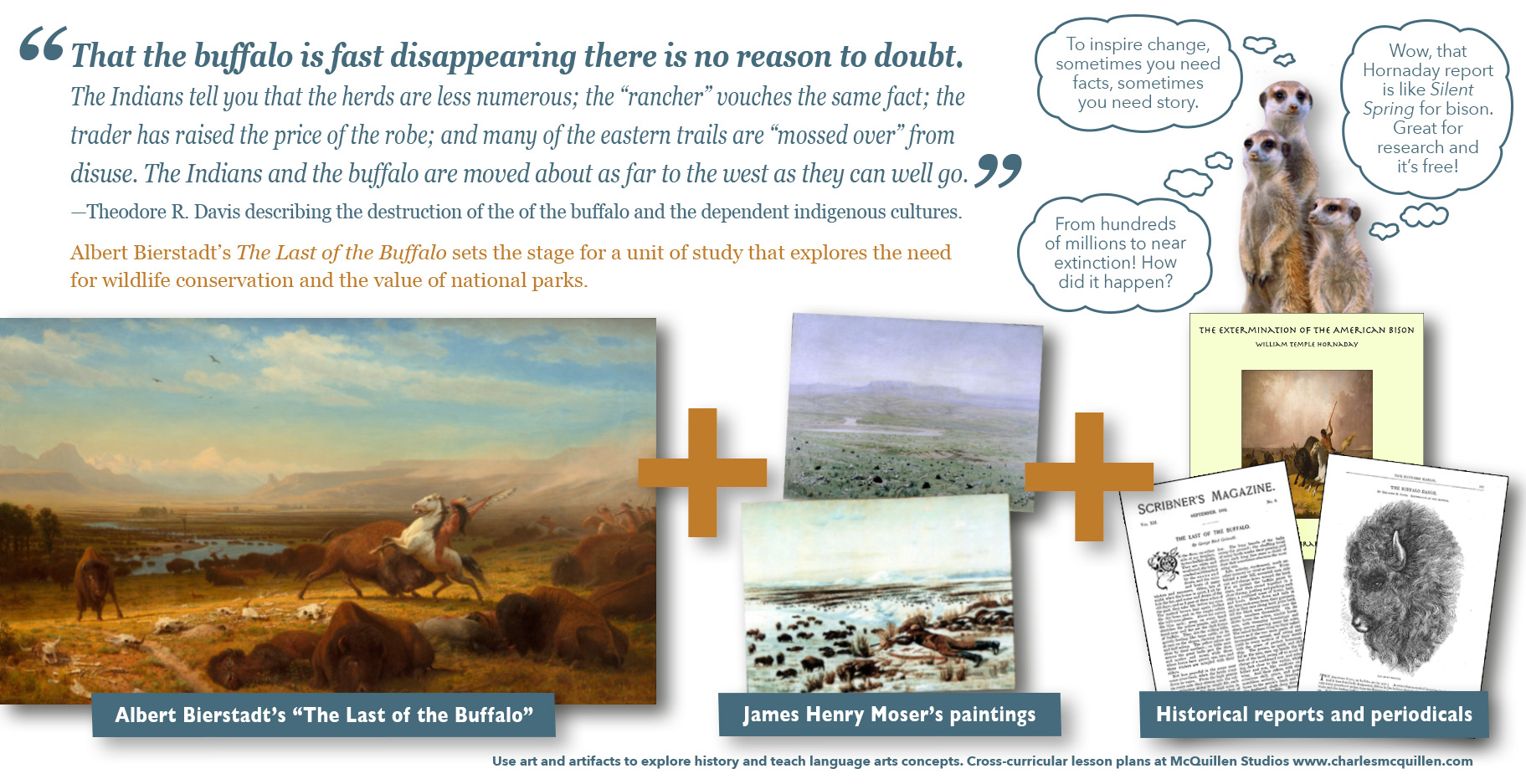

Point out and discuss: Albert Bierstadt developed his own characteristic style of art. This gallery shows five Bierstadt paining. The links below provide images that can be magnified.

- Indians Spear Fishing, 1862

- Valley of the Yosemite, 1864

- Merced River, Yosemite Valley, 1866

- Among the Sierra Nevada Mountains, 1868

- Giant Redwood Trees of California, 1874

Click on the gallery to enlarge images. Look across these paintings. What features and characteristics do these paintings have in common? Why might this style of art have been appealing in post-Civil War United States?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: Bierstadt depicted spectacular landscapes and accentuated their most dramatic features. The scenes are sweeping, majestic panoramas. Stone outcroppings, cascading waterfalls, towering mountains, roiling storms, and glowing light depict theatrical environments. The scenes are glorious and connect the land with the heavens. There is a strong sense of verticality. The mountains reach up to the sky. The light comes from deep in the sky and fills the scene like a visual trumpet of angels. Waterfalls come from an unknown source above and feed the land below. These are not pastoral manicured farmlands. This is awe-inspiring nature that dwarfs its human inhabitants. The only people shown are Native Americans who live close to the land. While gloriously raw and wild, this is not a dangerous wilderness, rather it is a land of promise. These are romantic paintings of Wild West before the West was “tamed.” The scenes are so over the top with drama and so theatrical they at times seem unreal. In depicting pristine and untarnished landscapes, these paintings might have special appeal to a public weary from the manmade carnage of war. In expressing the wonder of nature these painting would also have appeal for the masses in gritty industrial cities. Manifest Destiny was sweeping the country. By infusing these natural wonders with heavenly accents, these paintings brought an inspirational morality to that cause.)

Read a painting’s layers as an allegorical timeline

Point out and discuss: Describe the background, middle ground, and foreground. Can this be read as allegorical timeline? What story does it tell?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: The background shows majestic herds of buffalo in a spectacular pristine landscape. They graze peacefully. Their sheer numbers cause them to reign supreme over their domain. The blanket of buffalo in the background meanders with a river through the middle ground. The foreground, which is crammed with action, can be broken into two layers. The buffalo in the distant foreground flee Native American hunters on horseback. The buffalo’s dominance is challenged. Divergent lines and suggested motion instills a sense of chaos. The viewer can make out other animals from the environment. At the center a buffalo gores a white horse while the rider plunges a lance into the buffalo. Dead and dying buffalo lay in the immediate foreground. A Native American hunter and his horse lay dead among them. The bleached bones of long dead buffalo dot the foreground at once highlighting the present and future. A prairie dog, a standing buffalo, and dying buffalo look at the viewer. Are they implicating the viewer in the slaughter or imploring the viewer to take action. This visual timeline tells the story of the buffalo’s dominance as a species, its importance to Native cultures, and its impending destruction. The fallen Native American among the dying buffalo ties the extirpation of the buffalo with the destruction of the indigenous societies.)

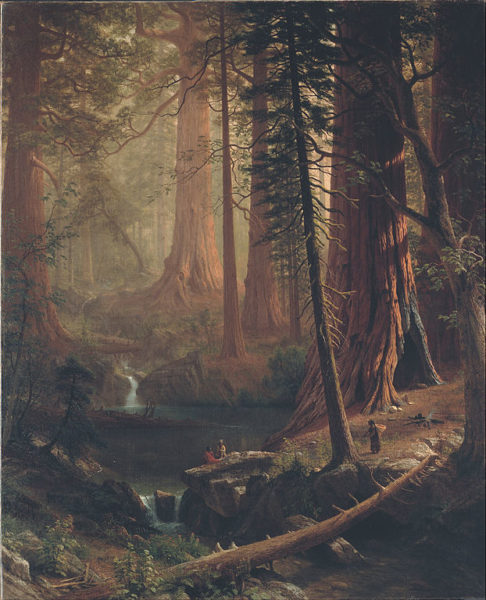

Compare The Last of the Buffalo with James Henry Moser’s The Deadly Still-Hunt and Where the Millions have Gone (1888).

Point out and discuss: The same year Albert Bierstadt created The Last of the Buffalo, James Henry Moser painted The Deadly Still-Hunt and Where the Millions have Gone. Two years later Moser was commissioned by the Smithsonian to recreate these paintings into two large murals for their Indian exhibit room. While both artists were troubled by the destruction of the once vast buffalo herds, their distinct artistic sensibility took them in decidedly different directions. Compare and contrast these different painting styles paying particular attention to how the buffalo, the hunter, and the landscape are rendered. What are the merits of each style?

The excerpt below from William T. Hornaday’s The Extermination of the American Bison can be used to introduce students to the historically significant method of still-hunting.

Of all the deadly methods of buffalo slaughter, the still-hunt was the deadliest.… For those greedy ones [hunters] the chase on horseback was ‘too slow’ and too unfruitful. That was a retail method of killing, whereas they wanted to kill by wholesale. From their point of view, the still-hunt or ‘sneak’ hunt was the method par excellence.…Having secured a position within from 100 to 250 yards of his game (often the distance was much greater), the hunter secures a comfortable rest for his huge rifle, all the time keeping his own person thoroughly hidden from view, estimates the distance, carefully adjusts his sights, and begins business.…The noise startles the buffaloes, they stare at the little cloud of white smoke and feel inclined to run, but seeing their leader hesitate they wait for her. She, when struck, gives a violent start forward, but soon stops, and the blood begins to run from her nostrils in two bright crimson streams. In a couple of minutes her body sways unsteadily, she staggers, tries hard to keep her feet, but soon gives a lurch sidewise and falls. Some of the other members of the herd come around her and stare and sniff in wide-eyed wonder, and one of the more wary starts to lead the herd away. But before she takes half a dozen steps “bang!” goes the hidden rifle again, and her leadership is ended forever. Her fall only increases the bewilderment of the survivors over a proceeding that to them is strange and unaccountable, because the danger is not visible. They cluster around the fallen ones, sniff at the warm blood, bawl aloud in wonderment, and do everything but run away. The policy of the hunter is to not fire too rapidly, but to attend closely to business, and every time a buffalo attempts to make off, shoot it down. One shot per minute was a moderate rate of firing, but under pressure of circumstances two per minute could be discharged with deliberate precision. With the most accurate hunting rifle ever made, a ‘dead rest,’ and a large mark practically motionless, it was no wonder that nearly every shot meant a dead buffalo.… Occasionally the poor fellow was troubled by having his rifle get too hot to use, but if a snow-bank was at hand he would thrust the weapon into it without ceremony to cool it off.

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: While Moser puts an emphasis on historical accuracy and a perfect physical reproduction, Bierstadt puts an emphasis on drama and evoking emotion. Unlike the still-hunt, which was a methodical killing of quietly grazing buffalo, Bierstadt fills his canvas with dramatic action—fleeing buffalo, charging horses, and death, up close and personal. While Moser accurately depicts how death came from a distance, Bierstadt brings the victims eye to eye with the viewer. Not only are the dying buffaloes imploring with a death stare, the eye sockets from the buffalo skulls strewn on the ground seem to lock on the viewer from the beyond. While Moser’s hunter is an unseen assassin shooting from on high, Bierstadt’s hunters are engaged in mortal hand-to-horn combat. While Moser’s landscape recedes gradually, Bierstadt creates a dramatic shift between foreground and background. The Last of the Buffalo is an epic image. It’s scale and content envelope the viewer. Moser, in contrast, creates smaller before and after scenes that involve thoughtful scrutiny and consideration. The coloration of the Bierstadt’s landscape further accentuates the drama. Note how Where the Millions have Gone’s blue green foreground fades to a peacefully analogous hazy blue horizon and sky. Bierstadt instead renders the same plains with yellows and oranges against a near complimentary blue sky. This dramatic effect is further enhanced by the rendering of light. The lighting in Where the Millions have Gone is even and flat whereas in The Last of the Buffalo spots of light guide the viewer across the canvas. Moser’s academic style strives for a perfect rendering of color and authentic details and is ideally suited for instructional purposes. Offering a sound scholarly perspective, it makes sense that Moser was commissioned by the Smithsonian to recreate these paintings into two large murals for their Indian exhibit room. As eye catching as it is emotionally engaging, Bierstadt’s painting would have broad popular appeal. While it doesn’t get caught up on depicting the literal cause of over hunting, this painting does highlight the interdependent relationship between the buffalo and the Native Americans and links the extirpation of the buffalo with the destruction of indigenous cultures. This paining is ideal for attracting attention and galvanizing discussion, and possibly action.)

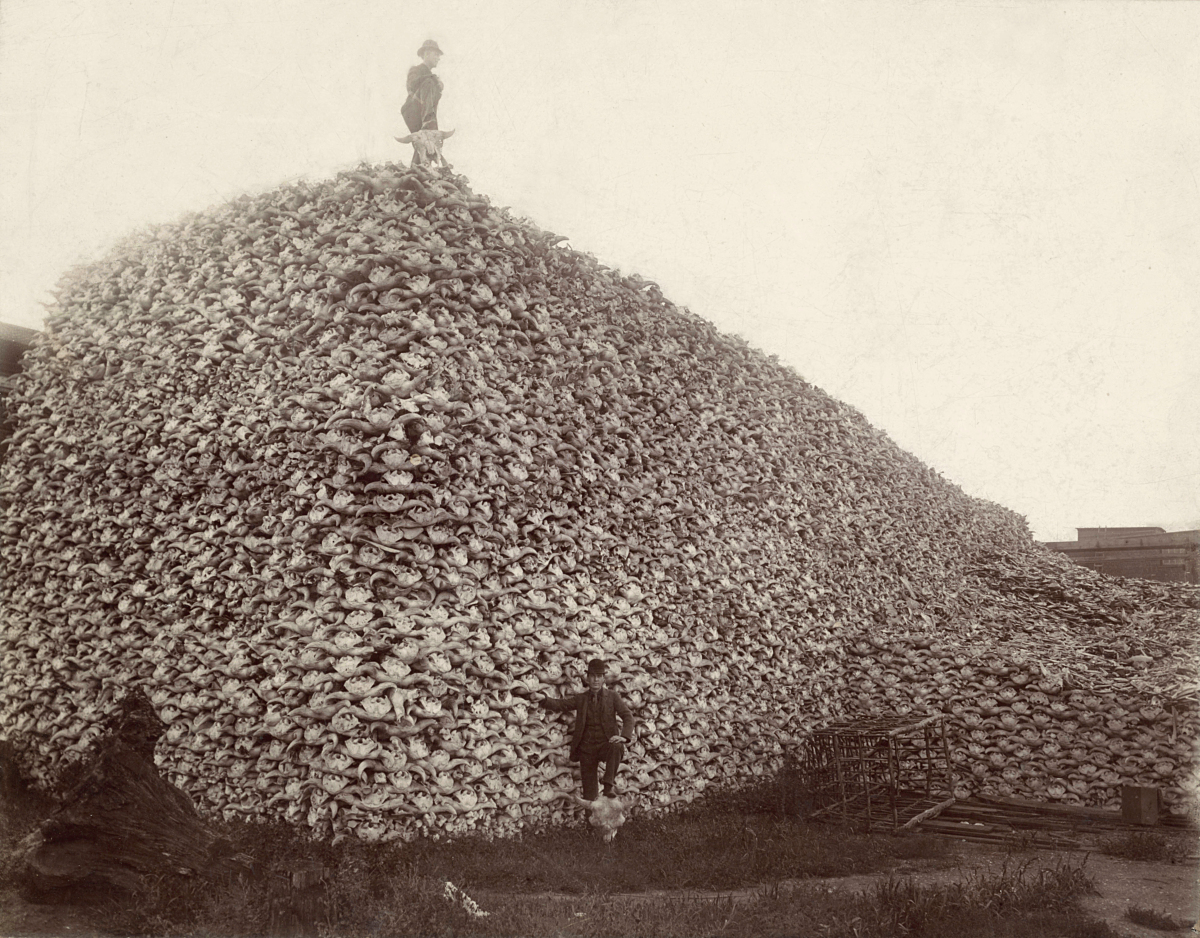

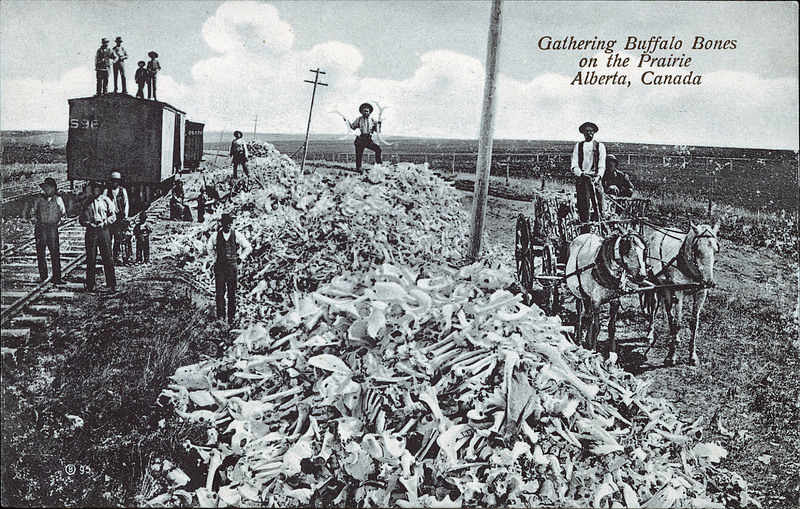

Extend the comparison with historic photographs.

The excerpt below from a letter by Arthur C. Bill (from the Kansas State Historical Society) can be used to introduce students to the massive bone harvest depicted in these photographs.

In the winter of 1874–’75 my cousin and I engaged in gathering buffalo bones from the prairies between Dodge City and Camp Supply, I. T. We purchased a yoke of oxen each, wagons, camp supplies, guns, ammunition, a pony and a saddle, etc. Government freighters hauling on way south were glad to haul for us on their return trip north. We piled the bones along the trail with our numbers on same. They hauled the bones to Dodge City and piled them along the A. T. & S. Fe tracks from where they were loaded into cattle cars and shipped to St. Louis to be used in refining sugar; their hoofs used to make glue; the horns to make buttons, combs, knife handles, etc. We received from $7 to $9 per ton for the plain bones, and $12 to $15 for the hoofs and horns.

Do these photographs reinforce and extend the ideas and feelings evoked in the paintings? Do you read historic photographs differently than paintings? What are the merits of historic photographs?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: Like the paintings, these photographs chronicle the rampant destruction of the buffalo herds. Offering a snapshot in time, they are less orchestrated and don’t tell a complete story. They are more matter of fact, less emotional. The photographs may seem to be a more objective record of the historic reality. The size of the bone piles help quantify the destruction.)

Think Like an Artist

The arts have long been used to call attention to and explore environmental issues. Art is uniquely suited to make the abstract and intangible felt. Environmental issues can be especially massive in scale and difficult to wrap your head around. Relationships can be especially abstract or subtle. Silent Suburb and The Bluebird are two environmental installations that explore issues around songbird habitat destruction. Both of these pages include additional links to other artists who use art to explore environmental issues. Review this art and the issues they highlight. Discuss your favorite works. How would you use art to highlight local environmental issues?

Life Lesson

Promote your ideas and be persistent in the face of natural resistance

In his book The Myths of Creativity: The Truth about How Innovative Companies and People Generate Great Ideas, David Burkus contends that Ralph Waldo Emerson’s popular maxim “build a better mousetrap and the world will beat a path to your door” is an unfortunate myth. He begins his argument by pointing out that the U.S. Patent Office has issued over 4,400 patents for better versions of the mousetrap; of those, only about 20 designs have ever been developed into commercially viable products. He goes on to present case studies to show that true innovation can be off-putting and creative people need to be persistent to overcome the natural resistance and hurdles they will surely face. Bierstadt’s success as an artist was due in no small part to his showmanship and his ongoing promotional efforts. As the opening quote in this reminds us, The Last of the Buffalo was initially rejected by art aficionados. Today, it is a prized painting in the National Gallery of Art and, in 1998, was honored as a commemorative U.S. Postage stamp. So, ignore the shame in shameless self-promotion and infuse persistence into your creative process.

Related Video and Multimedia Resources

- Albert Bierstadt’s “Last of the Buffalo” (2:07) offer a concise matter-of-fact overview of the painting.

- Lecture: “The Last of the Buffalo” with Peter Hassrick (55:44) explores how artists played an instrumental role in chronicling the transformation of the American frontier and saving the buffalo from extinction.

- American Landscape Painting: Albert Bierstadt and the American Land (1:09:55) is a lecture by Karen Quinn, a curator from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts that offers a scholarly overview of Bierstadt’s career as an artist and entrepreneur. The Last of the Buffalo is discussed from 44:46–49:16.

Integrating into Your Curriculum

Artists oftentimes use common visual strategies or signposts to alert viewers to significant details in their art. Here are some ideas for using these visual signposts to unpack a work of art. Remember, the close reading skills in art appreciation are similar to the close reading practices taught in reading.

Literature Links: What piece of literature would you partner with Albert Bierstadt’s The Last of the Buffalo? The Last of the Buffalo offers a number of avenues for literary exploration. In linking the demise of the buffalo with the destruction of Native American cultures, The Last of the Buffalo can be effectively paired with literature on Native American rights and Indian removal policies.

- Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (1970) is an Indian history of the American West that provides a detailed accounting of the post-1860 Indian removal campaigns including the destruction of the American buffalo.

Another literary avenue are heroic Western novels that romanticize the environment explore man against nature themes. Here are a few Western novels to consider.

- Zane Grey’s Riders of the Purple Sage (1912) is a trend-setting novel that established the western genre.

- John Williams’s Butcher’s Crossing (1960) is a “realistic” western that tells the tale of buffalo hunters, rapacious greed, and a misguided Emersonian quest to find oneself in the wilderness.

- Charles Portis’ True Grit (1968), while buffalo-free, is a revenge story that is included in many curricula and reflects common western themes such as frontier justice and honor codes.

- Jeff Guinn’s Buffalo Trail: A Novel of the American West (2016) is a contemporary western that follows a band of buffalo hunters who run afoul of vengeful Cheyenne, Comanche, and Kiowa warriors when they attempt to ply their trade in the forbidden Indian territory.

Another equally interesting avenue of literary exploration might be an analysis of nonfiction conservation literature. While Bierstadt may have been driven more by market demand, the preservation of the buffalo was a concern.

- Michael Punke’s The Last Stand (2007) is a detailed history of the destruction of American buffalo from vast herds of 30 million to a few dozen and the valiant struggle to save them from extinction.

- Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) documents the widespread harm caused by the indiscriminate use chemical pesticides, especially DDT. This environmental science book became an instant best seller and helped launch the grassroots environmental movement.

- Edward O. Wilson’s Anthill: A Novel (2010), while a work of fiction, is a science-based novel that explores the need to promote biodiversity and habitat preservation.

- Jennifer Price’s Flight Maps: Adventures with Nature in Modern America (2000) explores American’s philosophical and economic relationship with Nature. Her case study on the passenger pigeon, which closely parallels the destruction of the buffalo, reminds the reader that species preservation is not easy or a sure thing.

Writing Opportunity: Research Writing

The near extinction of the American buffalo, its preservation, and its eventual recognition as America’s first national mammal is a true American drama. This history is also an ideal platform for studying the implications of technology—especially the Shapes rifle, the train, and mass media—on massive species displacement, the destruction of indigenous cultures, and the transformation of the American West.

A Single Shared Text and Related Resources

If you prefer to use a single shared text for an inquiry study then consider William T. Hornaday’s The Extermination of the American Bison, with a sketch of its discovery and life history (United States National Museum for the Year Ending June 30, 1887). Available as a free ebook or a website, this is a comprehensive report by an influential leader in the effort to preserve the American bison. The chapter on conservation legislation is especially revealing. See excerpt below.

The first section of the bill provided that it shall be unlawful for any person, who is not an Indian, to kill, wound, or in any way destroy any female buffalo of any age, found at large within the boundaries of any of the Territories of the United States.…

- Mr. Eldridge thought there would be just as much propriety in killing the fish in our rivers as in destroying the buffalo in order to compel the Indians to become civilized.

- Mr. Conger said: “As a matter of fact, every man knows the range of the buffalo has grown more and more confined year after year; that they have been driven westward before advancing civilization.” But he opposed the bill!

- Mr. Lowe favored the bill, and thought that the buffalo ought to be protected for proper utility.

- Mr. Cobb thought they ought to be protected for the settlers, who depended partly on them for food.

- Mr. Parker, of Missouri, intimated that the policy of the Secretary of the Interior was a sound one, and that the buffaloes ought to be exterminated, to prevent difficulties in civilizing the Indians.

- Said Mr. Conger, “I do not think the measure will tend at all to protect the buffalo.”

- Mr. McCormick replied: “This bill will not prevent the killing of buffaloes for any useful purpose, but only their wanton destruction.”

— William T. Hornaday’s The Extermination of the American Bison, with a sketch of its discovery and life history, IV. Congressional Legislation for the Protection of the Bison

William T. Hornaday, Letter to Professor George Brown Goode, Director of the National Museum, expressing concerns about the conservation of bison (December 2, 1887). Here is a gallery of images related to his field trips to secure bison for the zoo and museum display. The Smithsonian Channel’s The Last Buffalo chronicles this near extinction and Hornaday’s story with their typical breathtaking video footage and compelling storytelling.

As Mr Parker’s intimation highlights, these conservation efforts ran up against the United States policy of starving Native Americans communities into submission through the destruction of their food sources, including the extermination of the buffalo.

It is certain that but little progress can be made in the work of civilization while the Indians are suffered to roam at large over immense reservations, hunting and fishing, and making war upon neighboring-tribes. It is only as they are led into habits of industry, and learn the advantages of labor, that anything can be done to elevate them.… I cannot regard the rapid disappearance of the game from its former haunts as a matter prejudicial to our management of the Indians. On the contrary, as they become convinced that they can no longer rely upon the supply of game for their support, will they turn to the more reliable source of subsistence furnished at the agencies, and endeavor to so live that that supply will be regularly dispensed. A few years of cessation from the chase will tend to unfit them for their former mode of life, and they will be the more readily led into new directions, toward industrial pursuits and peaceful habits. (Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior on the operations of the department for the year 1872)

Multiple Firsthand Accounts

These firsthand accounts in popular periodicals and scientific reports explore these themes from multiple perspectives.

- John Mills’ “A Brush with a Bison,” Harper’s Weekly, July 1851 (pp. 218–222) is a vivid, action-packed account of a buffalo hunt from a sportsman’s perspective.

- George D. Brewerton’s “In the Buffalo Country,” Harper’s Weekly, September 1862, (pp. 447–466) chronicles a trip across the Great Plains describing the indigenous cultures as well as the diverse plants, animals, and hardships.

- Theodore R. Davis’ “The Buffalo Range” in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol. XXXVIII, No. 224, 11, January 1869 (pages 147–163) is a comprehensive firsthand account that follows the buffalo from habitat and herd behavior to still hunting and market drivers.

- “Buffalo Hunting,” Harper’s Weekly, December 14, 1867, (pages 792 and 797) is a short news account of how buffalo are indiscriminately shot by passengers from a moving train.

- Buffalo land: an authentic account of the discoveries, adventures, and mishaps of a scientific and sporting party in the wild West; with graphic descriptions of the country; the red man, savage and civilized; hunting the buffalo, antelope … etc., etc., by William Edward Webb, drawings by Henry Worrall. Cincinnati: E. Hannaford, 1872 (504 pages).

- “Slaughtered for the Hide,” Harper’s Weekly, December 12, 1874 (p. 1022) is a brief news account on the wasteful practices of buffalo hunters.

- Franklin Satterthwaite’s “The Western Outlook for Sportsmen,” Harper’s Weekly, May 1889, pp. 873-880 explores big game sport hunting with a focus on the wasteful killing of buffalo.

- George Bird Grinnell’s “The Last of the Buffalo,” Scribner’s, September 1892, pp. 267–287 [illustrated] describes efforts to domesticate and breed bison, how Native cultures relied on them, and the technological advances that led to their near extermination.

- Hamlin Russell’s “The Story of the Buffalo,” Harper’s Weekly, April 1893, pp. 795–798 provides a concise overview of the buffalo in history up to its precarious existence.

- William T. Hornaday’s Wild life conservation in theory and practice: lectures delivered before the Forest School of Yale University, 1914, while sophisticated, offers a wealth of insight into turn-of-the-century wildlife conservation.

- Elahe Izadi’s “It’s official: America’s first national mammal is the bison.” The Washington Post, May 9, 2016 announces the new designation of the American buffalo as the national mammal.

Have small groups read different accounts and plot key events on a class timeline that maps this history. Use colored sticky notes to highlight common themes. As students share, capture their questions and points of interest. In addition to exposing varying, and deeply held, views of historic people and events, these documents provide insight into the use of argument writing, proxy arguments, and political maneuvering. If time and interest permits, have students research and respond to their questions.

The Question Formulation Technique (QFT) can help turn art observations and wonderings into inquiry-based research questions that build on student insights and interests. For ideas on how to structure inquiry circles see Stefanie Harvey and Smokey Daniels’ Comprehension and Collaboration: Inquiry Circles for Curiosity, Engagement, and Understanding.

How would you use this painting to build on one of your units of study? Please share if you have other ideas on how to teach The Last of the Buffalo by Albert Bierstadt as an English/language arts lesson plan.

Dear Crayon:

If you can form any idea of the scenery of the Rocky Mountain and of our life in this region, from what I have to write, I shall be very glad; there is indeed enough to write about a writing lover of nature and art could not wish for a better subject. I am delighted with the scenery. The mountains are very fine; as seen from the plains, they resemble very much the Bernese Alps, one of the finest ranges of mountains in Europe, if not the world. They are of granite formation, the same as the Swiss mountains and their jagged summits, covered with snow and mingling with the clouds, present a scene which every lover of landscape would gaze upon with unqualified delight. As you approach them, the lower hills present themselves more or less clothed with a great variety of trees, among which may be found the cotton-wood, lining the river banks, the aspen, and several species of the fir and the pine, some of them being very beautiful. And such charming grouping of rocks, so fine in color—more so than any I ever saw. Artists would be delighted with them —were it not for the tormenting swarms of mosquitoes. In the valleys, silvery streams abound, with mossy rocks and an abundance of that finny tribe that we all delight so much to catch, the trout. We see many spots in the scenery that remind us of our New Hampshire and Catskill hills, but when we look up and measure the mighty perpendicular cliffs that rise hundreds of feet aloft, all capped with snow, we then realize that we are among a different class of mountains; and especially when we see the antelope stop to look at us, and still more the Indian pursuer, who often stands dismayed to see a white man sketching alone in the midst of his hunting grounds. We often meet Indians, and they have always been kindly disposed to us and we to them; but it is a little risky, because being very superstitious and naturally distrustful, their friendship may turn to hate at any moment. We do not venture a great distance from the camp alone, although tempted to do so by distant objects, which, of course, appear more charming than those near by; also by the figures of the Indians so enticing, travelling about with their long poles trailing on the ground, and ttheir picturesque dress, that renders them such appropriate adjuncts to the scenery. For a figure-painter, there is an abundance of fine subjects. The manners and customs of the Indians are still as they were hundreds of years ago, and now is the time to paint them, for they are rapidly passing away; and soon will be known only in history. I think that the artist ought to tell his portion of their history as well as the writer; a combination of both will assuredly render it more complete.

We have taken many stereoscopic views, but not so many of the mountain scenery as I would wish, owing to various obstacles attached to the process, but still a goodly number. We have a great many Indian subjects. We were quite fortunate in getting them, the natives not being very willing to have the brass tube of the camera pointed at them. Of course they were astonished when we showed them pictures they did not sit for; and the best we have taken have been obtained without the knowledge of the parties, which is, in fact, the best way to take any portrait. When I am making studies in color, the Indians seem much pleased to look on and see me work; they have an idea that I am some strange medicine-man. They behave very well, never crowding upon me or standing in my way, for many of them do not like to be painted, and fancy that if they stand before me their likenesses will be secured.

I have told you little of the Wind River chain of mountains, as it is called. Some seventy miles west from them, across a rolling prairie covered with wild sage, the soap-plant (?) and different kinds of shrubs, we come to the Wasatch, a range resembling the White Mountains. At a distance you imagine you see cleared land and the assurances of civilization, but you soon find that nature has done all the clearing. The streams are lined with willows, and across them at short intervals they are intersected by the beaver dams; we have not yet, however, seen any of their constructors. The mountains here are much higher than those at home snow remaining on portions of them the whole season. The color of the mountains and of the plains, and, indeed, that of the entire country, reminds one of the color of Italy; in fact, we have here the Italy of America in a primitive condition.

We came up here with Col. F. W. Lander, who commands a wagon-road expedition through the mountains. At present, however, our party numbers only three persons: Mr. F_____, myself, and a man to take charge of our animals. We have a spring-wagon and six mules, and we go where fancy leads us. I spend most of my time making journeys in the saddle or on the bare back of an Indian pony. We have plenty of game to eat, such as antelope, mountain grouse, rabbit, sage-hens, wild-ducks, and the like. We have also tea, coffee, dried fruits, beans, a few other luxuries, and a good appetite—we ask for nothing better. This living out doors, night and day, I find of great benefit. I never felt better in my life. I do not know what some of your Eastern folks would say, who call night air injurious, if they could see us wake up in the morning with the dew on our faces!

We are about to turn our faces homeward again, the season being a short one here, and to avoid the full deluge on the plains, which renders the roads almost impassable.

—Albert Bierstadt in a letter to The Crayon (written July 10, 1859, published September 1859, vol 6, no 9) page 287.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.