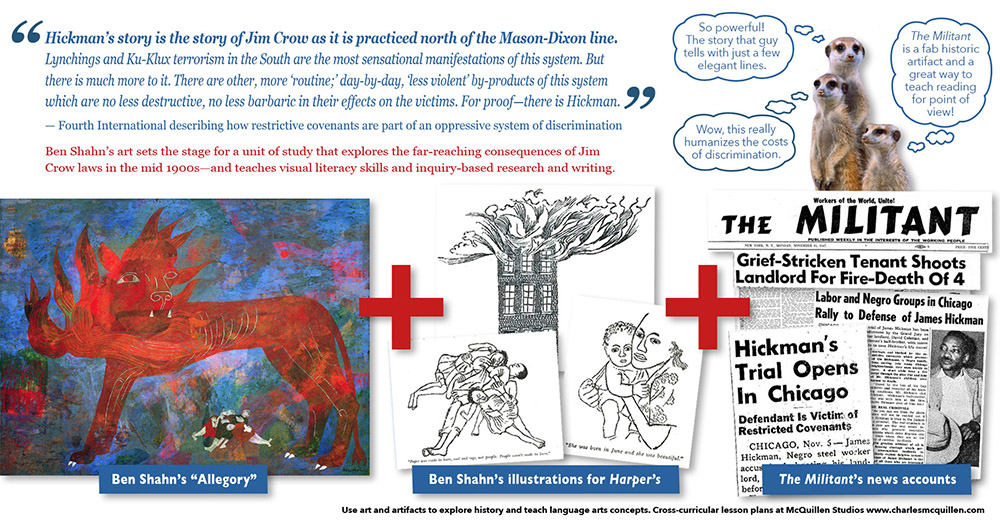

Teach close reading, symbolism, and housing discrimination with Ben Shahn’s Allegory

Ben Shahn’s Allegory is part of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth’s collection. Visit their website for detailed information and an image that can be magnified.

Ben Shahn’s Allegory is part of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth’s collection. Visit their website for detailed information and an image that can be magnified.

The immediate source of the painting of the red beast was a Chicago fire in which a colored man [James Hickman] had lost his four children.…I was asked to make drawings for the story and, after several discussions with the writer, felt that I had gained enough of the feel of the situation to proceed. I examined a great deal of factual visual material, and then I discarded it all. It seemed to me that the implications of this event transcended the immediate story; there was a universality about man’s dread from fire.…I now began to devise symbols of an almost abstract nature, to work in terms of such symbols. Then I rejected that approach too. For in the abstracting of an idea one may lose the very intimate humanity of it, and this deep and common tragedy was above all things human.…

The narrative of the fire had aroused in me a chain of personal memories. There were two great fires in my own childhood, one only colorful, the other disastrous and unforgettable.…The image that I sought to create was not one of a disaster; that somehow doesn’t interest me. I wanted instead to create the emotional tone that surrounds disaster; you might call it the inner disaster.…In the beast as I worked upon it I recognized a number of creatures; there was something of the stare of an abnormal cat that we once owned that had devoured its own young. And then there was the wolf.

To me, the wolf is perhaps the most paralyzingly dreadful of beasts, whether symbolic or real. Is my fear some instinctive strain out of my Russian background? I don’t know. Is it merely the product of some of my mother’s colorful tales about being pursued by wolves when she was with a wedding party, or again when she went alone from her village to another one nearby?…Whatever its source, my sense of panic concerning the wolf is real. I sought to implant, or, better, I recognized something of that sense within my allegorical beast.

— Ben Shahn, describing the motivations and inspirations that shaped his painting, Allegory. Excerpted from “The Biography of a Painting” in his book The Shape of Content, pages 26–32.

Look at Allegory. Before reading the excerpt above, tell students the title of the piece and ask what is going on in this picture? It may help to define two terms ahead of time.

- Allegory: While students may have seen allegorical artwork before, because the term is used as a title it might be beneficial to explain that an allegory is an artistic device that conveys hidden meaning through symbolic imagery.

- A chimera is a mythical or fabricated animal with parts taken from various animals. These figures are common throughout art history. In ancient Greece they were monstrous fire-breathing creatures.

This painting explores universal themes and feelings. See how much students can decipher through a group discussion. Encourage students to identify the evidence that supports their reasoning. Students should likewise be encouraged to share wonderings and voice confusions. As the conversation slows, explain you are going to read the artist’s descriptions of what he was thinking as he made this painting. After reading the excerpts ask how does this new insight change your understanding of the painting?

Begin with art history

Ben Shahn was born in Lithuania in 1898. In 1902 his father, a woodcarver and cabinetmaker, was exiled to a labor camp in Siberia for revolutionary activities. In 1906, Ben, his mother, and two siblings immigrated to Brooklyn, New York to rejoin his father who had fled Siberia. At the age of 13, after finishing elementary school, Shahn was apprenticed to a lithographer. He continued his schooling at night.

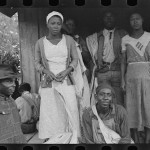

Early on, Shahn used his art to raise awareness of the social concerns and political issues of his time, such as the injustices of the Sacco and Vanzetti murder trial. From 1935 to 1938 Shahn worked as a photographer for the Farm Security Administration documenting the impact of the Great Depression on America’s farms and small towns. During World War II Shahn created posters and related art as a graphic designer for the Office of War Information and, later, for the Congress of Industrial Organizations. By the 1940s Shahn shifted from social realism to personal realism as he increasingly drew on common experiences, religious symbolism, and universal emotions to explore a shared humanity that transcended history and culture.

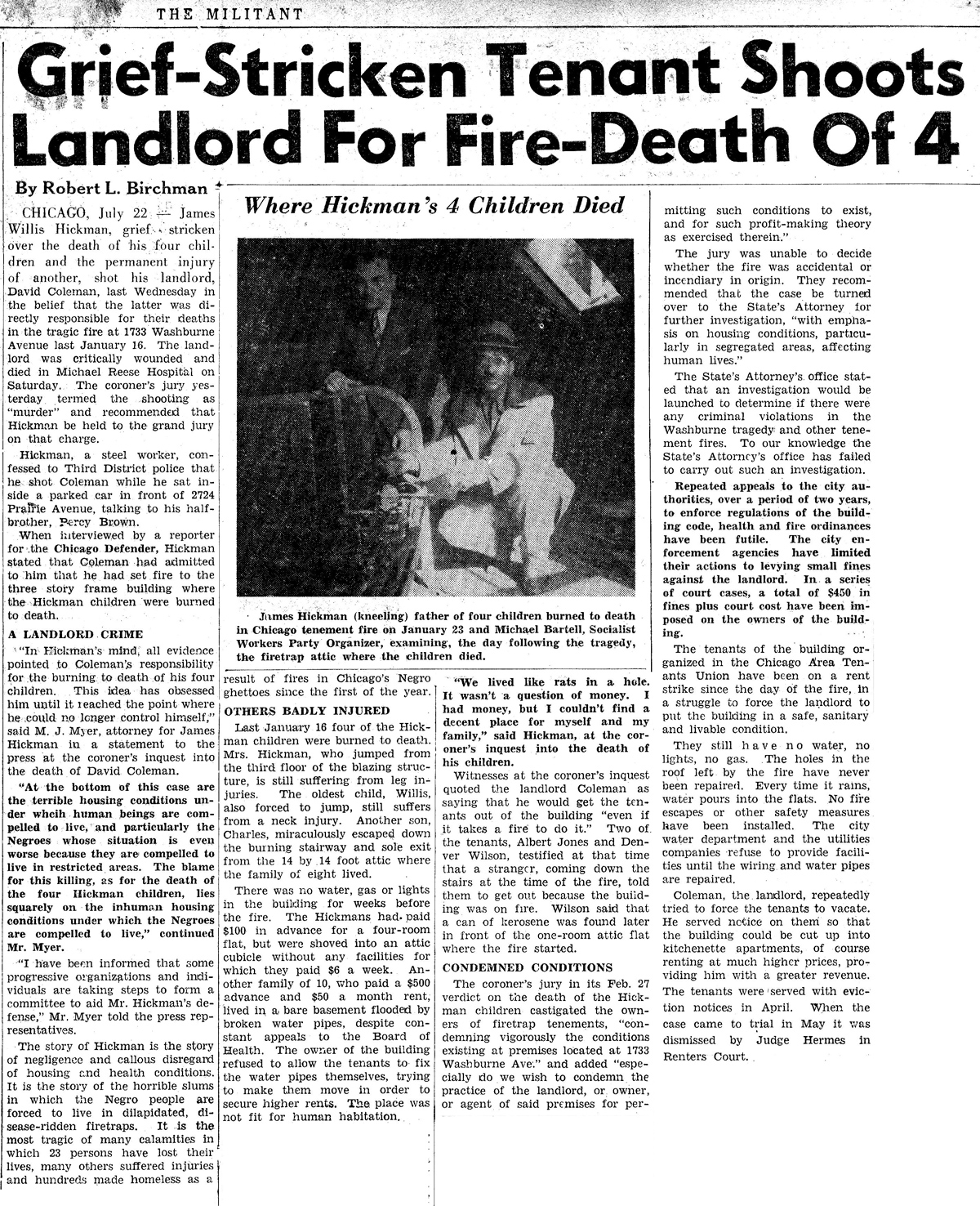

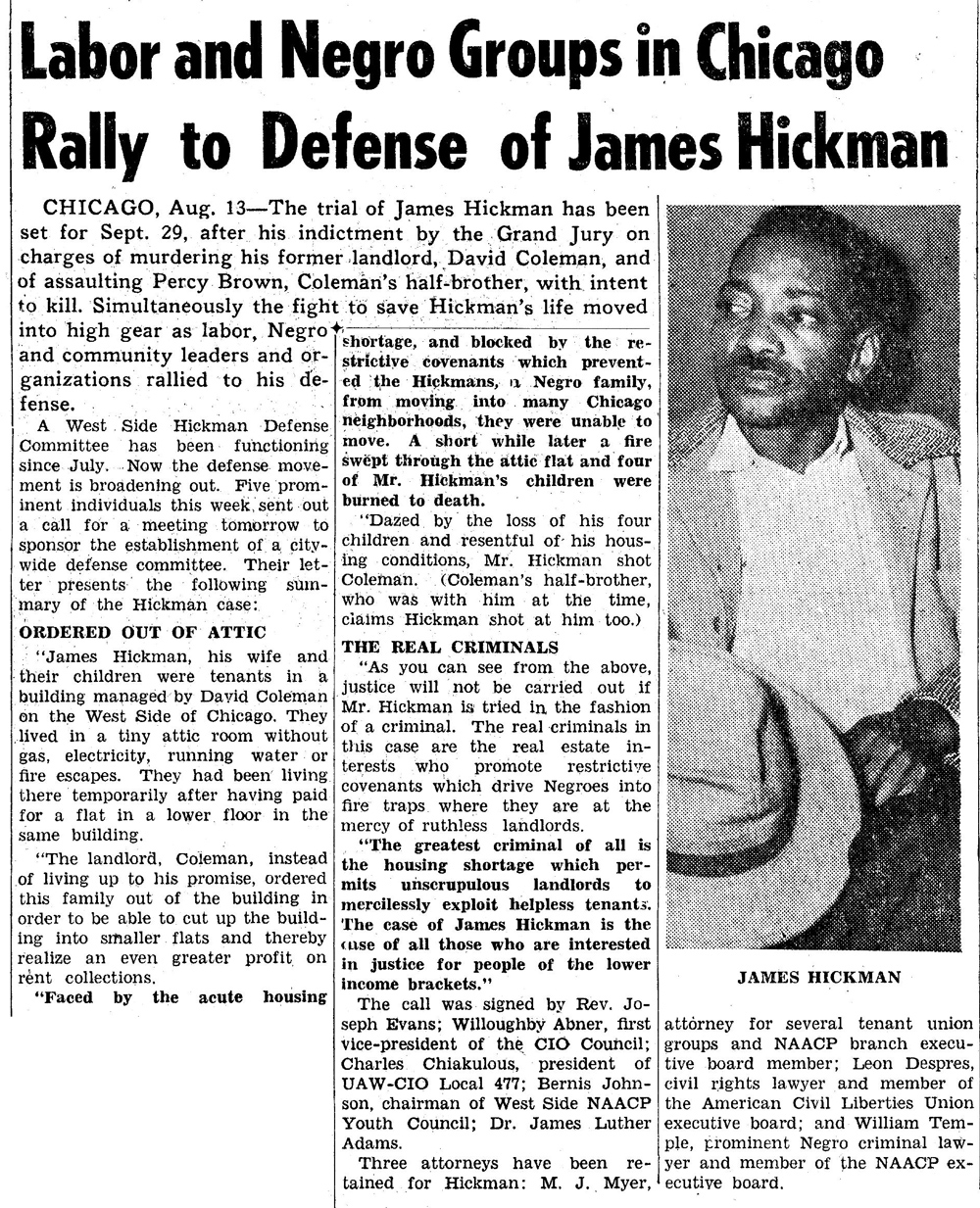

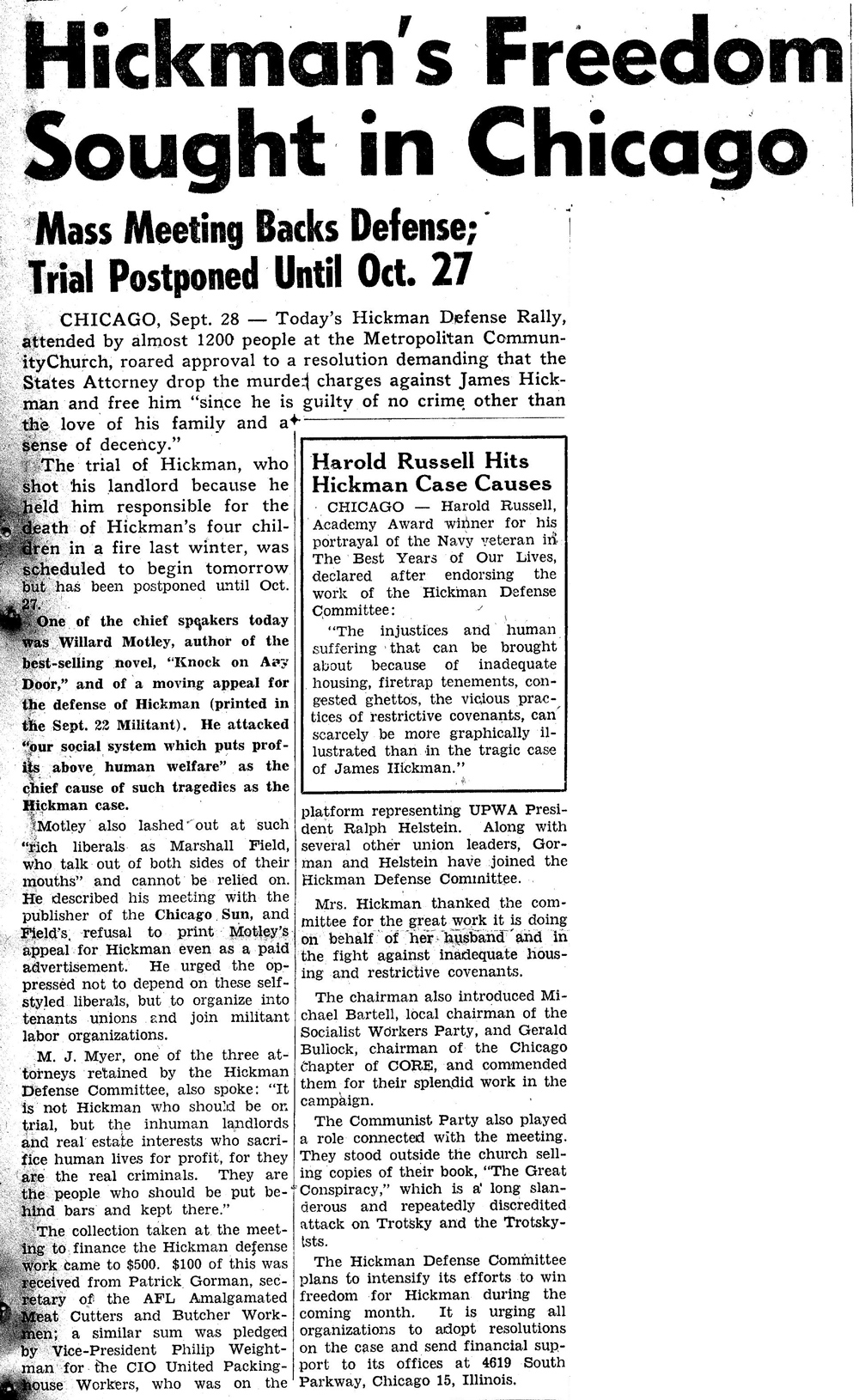

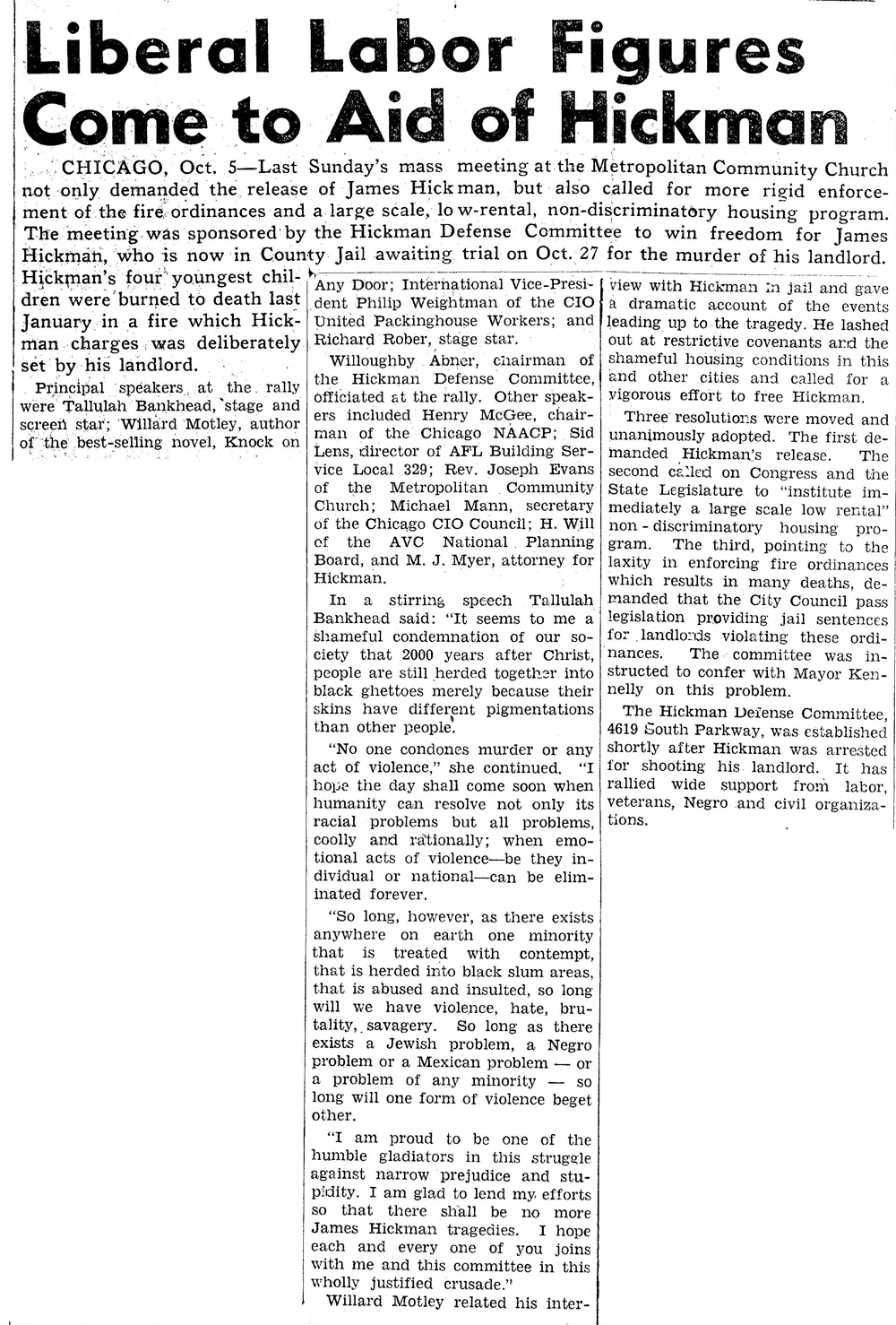

Shahn’s painting Allegory (1948) grew out of a series of illustrations he made to accompany John Barlow Martin’s magazine article on how poverty and discriminatory housing policies lead to a tragic fire that killed four siblings, Leslie (14), Elvena (9), Sylvester (7), and Velvena (4) Hickman. The children’s father, James Hickman, became increasingly distraught when the landlord, who had previously threatened to burn the building to drive the tenants out, appeared to get away with the crime. Seven months after the fire, overcome with grief and with a gun in hand, Hickman confronted, and eventually killed, the unrepentant landlord, David Coleman. Hickman then went home and waited quietly for the authorities to arrest him. Sympathetic to this mill worker’s plight, the Socialist Workers Party took up Hickman’s cause, funding his legal defense and organizing a highly publicized media campaign that declared him a victim of restricted covenants and related racial bias. A hung jury and growing public pressure resulted in James Hickman’s acquittal. (For a more comprehensive overview of this case see the writing connection at the end of this post.)

Working on these illustrations triggered recovered memories of two fires from Shahn’s own childhood, fires that may have had their own links to poverty and racism. Instead of focusing on an individual event, Allegory conflates these reflections with the horrors of the Holocaust into a symbolic image that expressed the emotional tone that surrounds disaster. Like Picasso’s Guernica, Shahn’s Allegory drew on local events, personal experiences, and shared symbols to express a universal plea for humanity and the innocent victims of intolerance and injustice.

Look like an art critic

Ben Shahn’s Allegory is part of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth’s collection. Visit their website to learn more.

Compare with Art History: Romulus and Remus

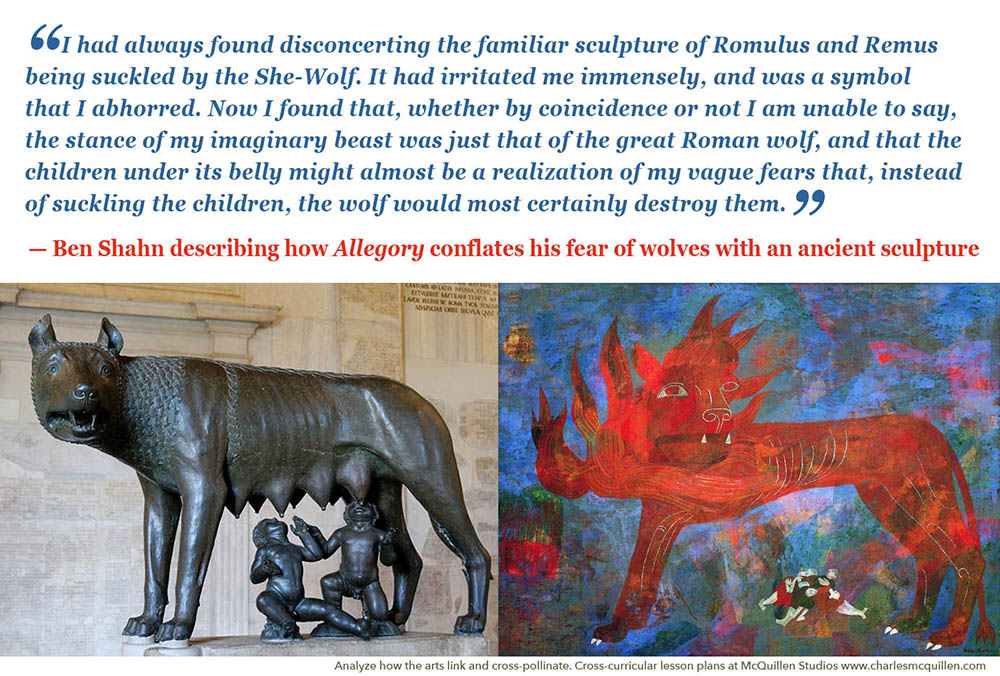

Point out and discuss: In describing the inspirations that shaped his chimera, Shahn described how his aversion to wolves influenced his view of an ancient sculpture of Romulus and Remus, twin boys abandoned to the wilds and saved by a she-wolf. They went on to found Rome. Shahn explained,

Then, to go on with the wolf image: I had always found disconcerting the familiar sculpture of Romulus and Remus being suckled by the She-Wolf. It had irritated me immensely, and was a symbol that I abhorred. Now I found that, whether by coincidence or not I am unable to say, the stance of my imaginary beast was just that of the great Roman wolf, and that the children under its belly might almost be a realization of my vague fears that, instead of suckling the children, the wolf would most certainly destroy them. But the children, in their play-clothes of 1908, are not Roman, nor are they the children of the Hickman fire; they resemble much more closely my own brothers and sisters.

Compare the Romulus and Remus sculpture with Allegory. How are these artworks similar and how does Shahn transform a heroic nurturing image and make it a menacing demonic image?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: The general composition for both of these artworks is similar. A large four-legged creature faces left and towers over the scene. Small children are vulnerably framed under its belly and between its legs. The differences between these images makes one menacing and the other nurturing. The Roman image is a life-like creature that looks as much like a domesticated dog as it does a wild wolf. The chimera’s appearance is supernatural and unnerving, as it hovers in a smoky nondescript environment. The painting’s splotchy background of blues, purples, and reds ominously evoke a hellish environment full of smoke and fire. Unlike the wolf, the chimera towers over the entire landscape like a foreboding, all-powerful force. Because the Roman figure is more recognizable and dog-like it seems less threatening. The Roman wolf seems to patiently pant, waiting as the boys suckle. The fangs and talons on the chimera are more pronounced and its raised paw makes it more threatening. The chimera doesn’t have burgeoning teats like the wolf, instead its ribs are accentuated which makes it seem hungrier and more savage. The chimera has a mane that erupts in flames which also makes it seem more dangerous. The Roman children are more active, taking in nourishment, while the children in Allegory are awkwardly heaped in a pile like discards and appear pale and lifeless. The chimera consumes its environment while the wolf provided sustenance.)

For your further consideration: Ben Shahn has written eloquently about Allegory and I would never dismiss what he has said, but when he talks about his art making process the subconscious seems to be at play. For example, in the statement above he says, “Now I found that, whether by coincidence or not I am unable to say,…” Tapping into the subconscious opens the door to interpretations that even the artist may not understand. I haven’t seen this anywhere else, so take this with a grain of salt, but there are events from his childhood that may further inform this painting. After Ben’s father was exiled to Siberia, Ben’s mother relocated to Vilkomer to be closer to family. It was here that Ben developed a deep attachment to his paternal grandfather Wolf-Leyb which translates to “Wolf-Lion.” In his biography Ben Shahn, An Artist’s Life, Howard Greenfeld describes this grandfather as “a huge man, known throughout the village for his enormous strength and for his kindness and warmth. He became, for his young grandson, not only a surrogate father but also a genuine hero.” Later, Greenfeld goes on to describe a vivid childhood memory where Ben walks with his grandfather through Vilkomer as a fire engulfs the village. Is Shahn conflating this tragic event, this tumultuous time of his life, and the security this larger than life grandfather provided? Shahn does say that the children in the painting are dressed more like his siblings than the Hickman children. In this light you can see the chimera as sheltering the children in this hellish environment. While Shahn’s description of the chimera is ominous, some critics have viewed it as protective, like the Roman wolf. If your students are having a similar debate, recounting these early childhood events may add to the discussion.

Compare media

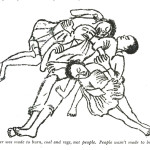

Point out and discuss: Click on the gallery to enlarge images. When Ben Shahn first created a series of illustrations about the Hickman fire he drew on factual accounts and physical evidence. For his painting Allegory, he abandoned these event-specific drawings as he tried to capture more universal emotions. Instead of creating an image of a disaster, he said he wanted to “create the emotional tone that surrounds disaster.” Compare the drawings from the original magazine article with Allegory. How are these artworks similar and what does Shahn do to make Allegory more universal and emotional?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: The pile of bodies under the chimera have strong parallels with the four Hickman children. The flames devouring the building are similar to the flames in the chimera’s mane. The illustrations are especially detailed. They show the children with greater individuality than is seen in the painting. You can distinguish their features and even get a sense of their personalities. The children in the painting appear more like a jumble of arms and legs. (Some contend this evokes Holocaust victims.) The detailed clothing and other artifacts locate the drawings in time and place. The painting’s hazy nondescript background makes the composition timeless. The hybrid nature of the chimera transcends culture and history imbuing a general sense of fear and anxiety, which is further accentuated by its flaming red features against a dark foreboding background.)

Identify a unifying sensibility

Photographs: Citizens of Columbus, Ohio, One of the few remaining inhabitants of Zinc, Arkansas, Omar, West Virginia, Square dance, Skyline Farms, Arkansas, Arkansas Cotton Pickers.

Posters: We French Workers warn you…, Lidice poster, Register to Vote, We Want Peace, Lest We Forget.

Point out and discuss: Ben Shahn was an accomplished illustrator, painter, photographer, and graphic designer. You have looked at his drawings and a painting. These galleries show his photographs and posters. Click on the gallery to enlarge images. Look across all of these art forms. How would you describe the common artistic sensibility that unifies all of these works?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: The work has a strong narrative undercurrent. They tell a story about the people they depict. Drawing on a figurative tradition, they emphasize human beings, oftentimes making the background spare and nondescript so the people seem to pop off the surface. Shahn has a special affinity for laborers at work and at play. His work also emphasizes social justice issues, drawing attention to the vulnerable, oppressed, and those on the margins of society. He uses a confident authoritative line, precise details, and spare, direct compositions to depict poverty, protest, and social reform. His art is not academic or studio based, rather he is driven by democratic ideals that celebrate family and community. He makes art about everyday events and people for a general audience. Ranging from social documentary to political propaganda, Shahn’s art breaks down the barriers between high art and mass media.)

The Library of Congress offers thousands of Shahn’s Depression-era photographs. Have students sift through them and pick photographs to discuss why they resonate with them.

Think Like an Artist

Ben Shahn’s chimera grew out of his personal fears of wolves and his memories of a disturbing family pet that devoured its young. Create your own chimera. It can be either a threatening or a comforting creature. Just create it based on your feelings and experiences. Focus on the most memorable features of your source animals and blend them together into a single hybrid creature and then consider what medium would best render this supernatural being.

Life Lesson

Cast your experiential and intellectual net broadly and integrate your catch. Ben Shahn was as prolific with words as he was with artistic media. His Norton Lectures (see The Shape of Content) is an excellent read, offering insight into the creative mind. He writes eloquently about the value of nonconformity, empathy, and the pursuit of truth. The final of the six lectures titled “The Education of an Artist” offers life lessons for all creatives. Shahn explains that there is no set course of study for cultivating creativity, rather in life and education your focus needs to be on honing your perceptivity. (Today, this is called mindfulness.)

Attend a university if you possibly can. There is no content of knowledge that is not pertinent to the work you will want to do. But before you attend a university work at something for awhile. Do anything. Get a job in a potato field; or work as a grease monkey in an auto repair shop. But if you do work in a field do not fail to observe the look and feel of earth and of all things that you handle—yes, even potatoes! Or, in the auto shop, the smell of oil and grease and burning rubber.… (page 113)

After explaining how to mine life’s experiences by immersing yourself in talk, listening, and observing, Shahn explains the need to actively integrate this new knowledge and understandings.

Being integrated, in the dictionary sense, means being unified. I think of it as being a little more dynamic—educationally, for instance, being organically interacting. In either sense, integration implies involvement of the whole person, not just selected parts of him; integration, for instance, of kinds of knowledge (history comes to life in the art of any period); integration of knowledge with thinking—and that means holding opinions; and then integration within the whole personality—and that implies holding some unified philosophical view, and attitude toward life. And then there must be the uniting of the personality, this view, with the creative capacities of the person so that his acts and his works and his thinking and his knowledge will be in unity. Such a state of being, curiously enough, invokes the word integrity in its basic sense: being unified, being integrated. (pages 116–117)

Integration in our compartmentalized world cannot be taken for granted. It is too easy to relegate certain kinds of thinking and seeing to specified activities. Creative people need to open themselves to new knowledge and experiences and rigorously integrate this into a unified worldview.

Related Videos and an Interview

- Art as Activism: The Compelling Paintings of Ben Shahn (9:59) This documentary chronicles Ben Shahn’s life, work, and motivations.

- This Is Ben Shahn (Clip) (2:12) This clip from a larger commercial video offers archival footage of Ben Shahn discussing his art and guiding philosophy.

- An oral history interview with Ben Shahn, The Smithsonian Archives of American Art, 1964

Integrating into Your Curriculum

Artists oftentimes use common visual strategies or signposts to alert viewers to significant details in their art. Here are some ideas for using these visual signposts to unpack a work of art. Remember, the close reading skills in art appreciation are similar to the close reading practices taught in reading. This video offers an overview of the art-based inquiry study.

Literature Links: What piece of literature would you partner with Ben Shahn’s Allegory? Allegory offers a unique opportunity to analyze a range of related nonfiction texts and explore an artist’s response to a real-world event that is ripe with social justice issues that are contemporary and universal.

Literature Links: What piece of literature would you partner with Ben Shahn’s Allegory? Allegory offers a unique opportunity to analyze a range of related nonfiction texts and explore an artist’s response to a real-world event that is ripe with social justice issues that are contemporary and universal.

- John Bartlow Martin’s “The Hickman Story” in Harper’s Magazine (August, 1948) is the original magazine article that introduced Shahn to the tragic fire that inspired Allegory. Martin uses Hickman’s story and words to expose working poverty, institutional racism, and housing discrimination in post World War II Chicago.

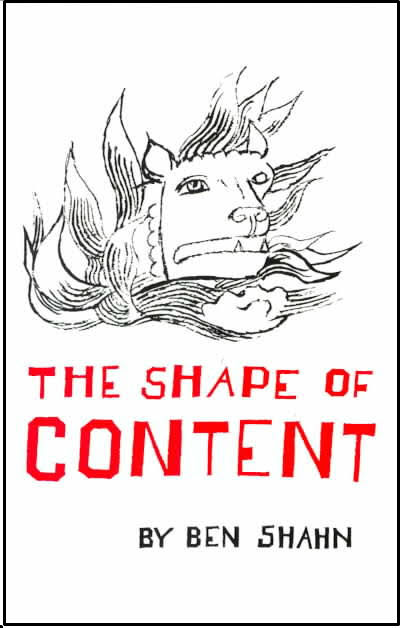

Ben Shahn’s “The Biography of a Painting” (pages 25–53) in The Shape of Content (1957) describes in the artist’s own words the influences that informed Allegory and how he used local events and personal experiences to explore universal feelings.

Ben Shahn’s “The Biography of a Painting” (pages 25–53) in The Shape of Content (1957) describes in the artist’s own words the influences that informed Allegory and how he used local events and personal experiences to explore universal feelings.- Joe Allen’s “The Fight to Save James Hickman in Post-WWII Chicago: A Previously Unknown Individual” in the Dissident Voice: A radical newsletter in the struggle for peace and social justice (July 3, 2009) introduces the general ideas and facts behind his history of the Hickman fire and murder trial. This video uses Shahn’s drawings and photographs to introduce the book.

- This topic lends itself to related muckraker literature. Consider these titles:

– Jacob Riis’ How the Other Half Lives examines New York’s slums

– Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle chronicles Chicago’s meat packing industry

– Ida B. Wells wrote numerous articles on Jim Crow laws

Writing Opportunity: Inquiry-based research and writing View an overview video. For history/social studies teachers who are teaching about Jim Crow laws, institutional racism, and the rise of ghettos in post World War II America, the Hickman family tragedy as chronicled in the socialist newspaper, The Militant offers a unique opportunity to learn from historical artifacts and put a face to larger social issues. As the related journal the Fourth International explains,

Every so often a previously unknown individual suddenly attracts wide attention. There is usually a social reason for this. The story connected with the particular case epitomizes the plight of voiceless millions, focusing attention on the needs of one group and the crimes of another, bringing into the light of day the festering rottenness of class society..… Hickman’s story is the story of Jim Crow as it is practiced north of the Mason-Dixon line. Lynchings and Ku-Klux terrorism in the South are the most sensational manifestations of this system, and they receive the most publicity and attention. But there is much more to it. There are other, more “routine;’ day-by-day, “less violent” by-products of this system which are no less destructive, no less barbaric in their effects on the victims. For proof – there is Hickman.

“The Case of James Hickman” from Fourth International, September–October 1947, Vol. 8 No. 8, pp.229–230.

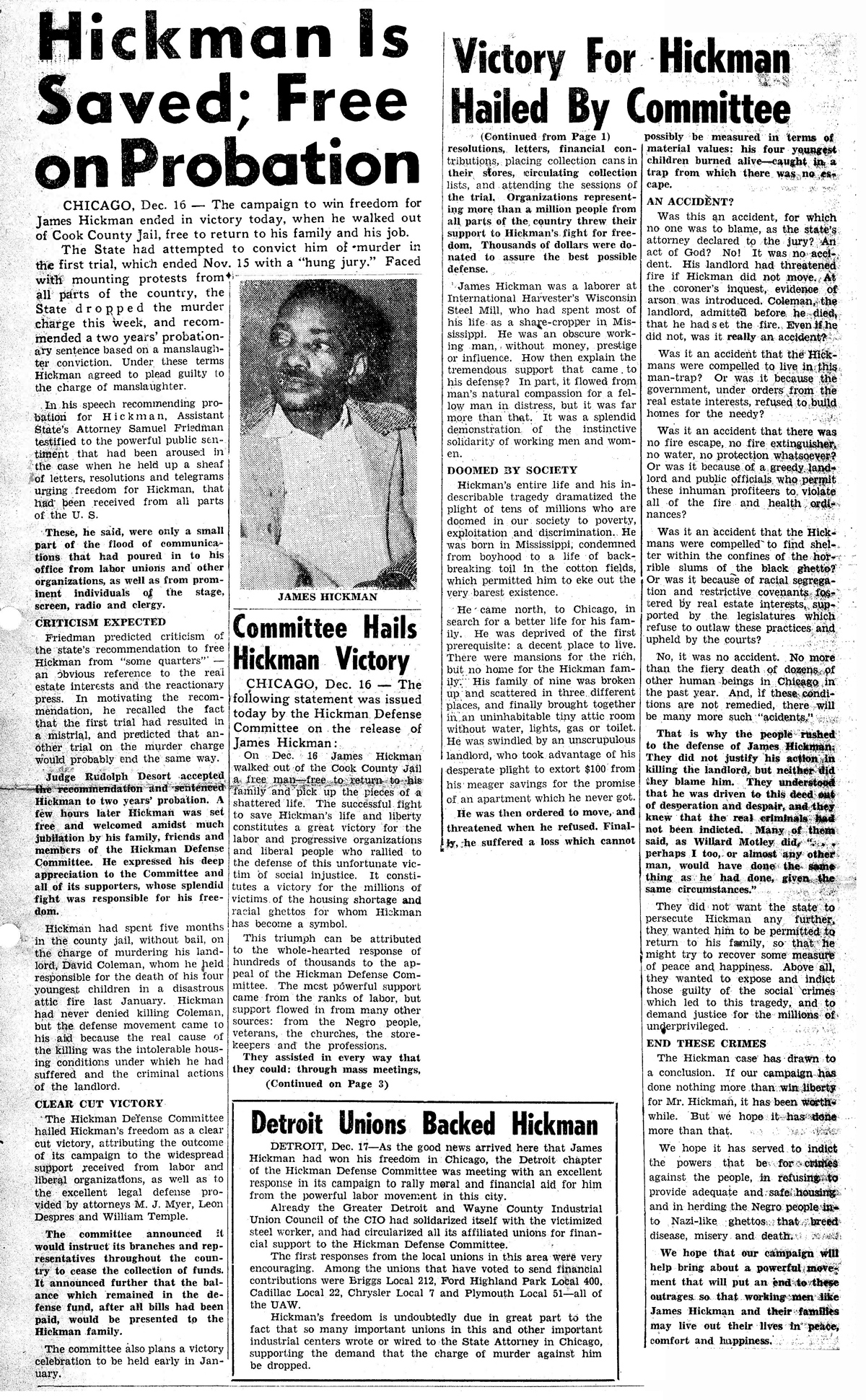

The Hickman tragedy personifies the plight many black families suffered in cities throughout the United States. Reading these news accounts puts a face and a story to oppressive discrimination endured by many. Here is a gallery of especially telling articles. Click on the image to expand. Drag the jpg into a Word document to create your own handout.

- “Grief-stricken tenant shoots landlord for fire-death of 4” (The Militant, August 4, 1947, page 5)

- “Hickman case victims tell tragic story to ‘Militant,’” (The Militant, August 11, 1947, page 6)

- “Labor and Negro groups in Chicago rally to defense of James Hickman” (The Militant, August 18, 1947, page 6)

- “Defense committee asks state to free Hickman” (The Militant, September 15, 1947, page 6)

- “Hickman’s freedom sought in Chicago – mass meeting backs defense; trial postponed until Oct. 27” (The Militant, October 6, 1947, page 1)

- “Liberal labor figures come to aid of Hickman” (The Militant, October 13, 1947, page 6)

- “Hickman’s trial opens in Chicago – defendant is victim of restricted covenants” (The Militant, November 10, 1947, page 1)

- “Trial of James Hickman nears climax in Chicago” (The Militant, November 17, 1947, page 1)

- “Hickman jury disagrees new trial set for Jan. 5” (The Militant, November 24, 1947, page 1)

- “Hickman’s vindication at trial spurs broader defense drive” (The Militant, December 1, 1947, page 6)

- “Hickman defense chairman outlines committee’s plans” (The Militant, December 15, 1947, page 6)

- “Hickman is saved; free on probation” (The Militant, December 22, 1947, page 1)

- “Committee Hails Hickman Victory” (The Militant, December 22, 1947, page 1 and 5) — This article summarizes the story and its universal themes.

Have small groups read different articles and plot key events on a class timeline that maps how the story evolved. As students share, capture their questions and points of interest. These articles touch on Jim Crow laws, restricted covenants, and the rise of ghettos. As historical artifacts, these articles also provide insight into socialism in the United States and the values and concerns of the Socialist Workers Party. They offer an opportunity to teach students how to read for point of view. Through The Militant’s news coverage related (and contemporary) world events spill in and around this story. I was especially intrigued how a form of social media was used to raise awareness and exert pressure on the legal system. Have students research and respond to their questions.

Have small groups read different articles and plot key events on a class timeline that maps how the story evolved. As students share, capture their questions and points of interest. These articles touch on Jim Crow laws, restricted covenants, and the rise of ghettos. As historical artifacts, these articles also provide insight into socialism in the United States and the values and concerns of the Socialist Workers Party. They offer an opportunity to teach students how to read for point of view. Through The Militant’s news coverage related (and contemporary) world events spill in and around this story. I was especially intrigued how a form of social media was used to raise awareness and exert pressure on the legal system. Have students research and respond to their questions.

The Question Formulation Technique (QFT) can help turn art observations and wonderings into inquiry-based research questions that build on student insights and interests. For ideas on how to structure inquiry circle see Stefanie Harvey and Smokey Daniels Comprehension and Collaboration: Inquiry Circles for Curiosity, Engagement, and Understanding.

How would you use this painting to build on one of your units of study? Please share if you have other ideas on how to teach Allegory by Ben Shahn as an English/language arts lesson plan.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.