Teach close reading skills, expressive brushwork, and prizefighting with George Bellows’ Stag at Sharkey’s. Share the Look and Learn interactive module with your students.

George Bellow’s Stag at Sharkey’s is in Cleveland Museum of Art’s collection. Visit their website for detailed information. Click on the painting for a high quality image that can be magnified.

In 1896 the Horton Law legalized boxing in New York State. The law however did not regulate bouts, making them ripe for corruption by gamblers and organized crime. In 1900, the Lewis Law repealed the flawed act, essentially outlawing prizefighting, except for fistic exhibitions in private boxing clubs for the entertainment of dues-paying members. This loophole spawned illicit “fight clubs.” Bars would stage impromptu bouts in their private backrooms where attendees paid membership dues instead of admission fees. Fighters would “join” the club for the night to pummel other “members.” This farce was perpetuated when boxers entering the ring were announced as “both members of this club.” One of the more renowned clubs was run by “Sailor” Tom Sharkey, a former heavyweight contender with his own colorful fight history. Tom Sharkey’s Athletic Club was a saloon across the street from George Bellows’ art studio and became a haunt for George and his friends.

…Before I married and became semi-respectable, I lived on Broadway opposite the Sharkey Athletic Club where it was possible under the law to become a ‘member’ and see the fights for a price.

…I don’t know anything about boxing. I am just painting two men trying to kill each other.

…Who cares what a prize-fighter looks like? It’s his muscles that count.

…I am not interested in the morality of prize fighting. But let me say that the atmosphere around the fighters is a lot more immoral than the fighters themselves.

—George Bellows explaining the inspiration for his three early boxing canvases and responding to critics who complained about certain details.

A prize-fight is simply brutal and degrading. The people who attend it, and make a hero of the prize-fighter, are —excepting boys who go for fun and don’t know any better,—to a very great extent, men who hover on the border-line of criminality; and those who are not are speedily brutalized, and are never rendered more manly. They form as ignoble a body as do the kindred frequenters of rat-pit and cock-pit.

—Theodore Roosevelt contrasts prizefighting with the benefits of amateur athletics in his essay “Professionalism” in Sports The North America Review, Vol 151, January 8, 1890, pages 187–191.

The canvases [“Club Night” (1907), “Stag at Sharkey’s” (1909), and “Both Members of This Club” (1909)] were painted at a time when boxing was illegal in New York State—a time, it’s said, when more boxing matches took place weekly than ever before or since. In these private clubs, under police “protection,” men of disparate ages, weights, and experience were matched; there were no enforced regulations; no ringside doctors, of course; and referees rarely stopped fights. If a boxer died, his body was summarily dumped in an alley or in the river, without identification. This is New York City, the hellish perversion of the American dream, its slum life powerfully depicted in other, even more crowded canvases of Bellows’…

—Joyce Carol Oates, “Stag at Sharkey’s” in George Bellows: American Artist

Look at Stag at Sharkey’s. Before reading the excerpts above, tell students the title of the painting and ask what is going on in this painting? Because boxing’s popularity has waned in recent decades students may identify this as mixed martial art or other combat sport. There is no need to correct them as this association may inform future discussions. Encourage students to identify the evidence that supports the reasoning behind their interpretations. Students should likewise be encouraged to share wonderings and voice confusions. As the conversation slows, explain you are going to read quotes from the artist about his intentions in making the painting and excerpts about prizefighting in early 1900s United States. After reading the excerpts ask how does this new insight change your understanding of the painting?

NOTE: Stag has multiple meanings and that may confuse students. Here are a few examples.

- The Cleveland Museum of Art, which owns the original painting states, “Whenever an outsider competed at the club, he was given temporary membership and known as a ‘stag.’” So a stag is the fighter?

- Describing a lithograph of the same name, Marty Krause, a curator from the Indianapolis Museum of Art states, “A stag was a private entertainment prizefight for the members of the club.” So a stag is the exclusive event?

- Sister Wendy assumes a more metaphorical interpretation for stag when she states. “…the boxers themselves are reminiscent of stags in nature, still graceful while locked in combat.”

A closer look at the origins of the word provides added insight and a vocabulary-building opportunity. The term likely comes from the Nordic steggi meaning “a male animal.” Stag can mean a male deer, or in Scotland it means “a young unbroken horse.” The term has Germanic roots that originally meant “male animal in its prime.” Going stag also means going to a social event alone, unaccompanied by a woman. In mid 1800’s American English the term came to mean “pertaining to or composed of males only” such as a stag party, a pre-wedding party for a groom and his male friends to mark the end of his unattached life. In the 1960’s the disreputable nature of this term was further reinforced when porn films were called stag movies. So, while the term can have multiple readings, all these definitions center around male virility. The broad interpretation of the term stag in this title suits this painting that explores male identity—both sordid (the spectators) and heroic (the fighters).

Begin with art history

George Bellows was born in 1882 in Columbus, Ohio. Bellows’ artistic talents were recognized at a young age when his elementary-school teachers asked him to create holiday drawings on the blackboard. Jealous classmates teased him relentlessly for being an “artist.” Bellows attributed his muscular development to the fisticuffs he endured when these taunts became physical. Socially and physically awkward, Bellows struggled to make the neighborhood baseball team. He eventually won acceptance as the team’s manager when he promised to promote the team in the local papers. While filling in for absent players, Bellows’ skills developed and he became an accomplished shortstop. He went on to become a basketball and baseball star at Ohio State University.

While his father encouraged George to continue his studies and become an architect like himself; and while the Cincinnati Reds encouraged George to play baseball for them; George pursued his first love, art. He left college before the end of his junior year to study art in New York City. It was at the New York School of Art that George studied under Robert Henri, an influential artist who encouraged his students and colleagues to challenge academic standards and to aggressively explore a range of painting techniques and real world subjects. This focus on contemporary life, including gritty street scenes, resulted in this loosely knit group of artists being called the Ashcan School, and what some derisively referred to as the “Apostles of Ugliness.”

When not in class, George roamed the streets of New York sketching everyday life in the burgeoning city. He won acclaim for realistic paintings of grimy street scenes, construction sites, and immigrant neighborhoods. His early portraits celebrated working class children and his illustrations for the socialist journal The Masses satirized the hypocrisy of social and religious leaders. His paintings of prizefighters from this time period may be his best-known works. While drawing on the techniques of past masters like Goya and Rembrandt, Bellows’ depictions of this popular pastime evoke the energy, savagery, and heroic struggle of urban life in turn-of-the-century United States.

Throughout his career Bellows regularly challenged himself through exploration and reinvention. Because he found inspiration in the everyday, Bellows’ work changed as his world changed. As his own family grew, paintings of street urchins gave way to portraits of his wife and daughters. As he traveled the country, gritty urban scenes became dramatic seascapes and bucolic landscapes. He expanded his art making beyond painting and became a renowned lithographer as well. The fluid and unselfconscious Bellows also became increasingly theoretical and programmatic in his approach to color (H. G. Maratta’s Color Theory and Denman Ross’ Painter’s Palette) and design (J. Hambidge’s Dynamic Symmetry). Unlike many of his generation, Bellows never went to Europe to find his artistic sensibility. This, coupled with his deep roots in Ohio, training in New York, and extensive travels around the United States, makes Bellows a distinctly American artist.

Look like an art critic

This image of Stag at Sharkey’s from the Cleveland Museum of Art lets you magnify the painting and see exquisite detail. Thank you Cleveland Museum of Art!

Comparing styles of paintings

Point out and discuss: (Click on a gallery image to enlarge or click on the links below for exquisitely detailed images.) While Stag at Sharkey’s and Bellows’ two other boxing paintings were critically acclaimed, they were not the first boxing painting by a famous American artist. The realist painter Thomas Eakins likewise painted boxers to equal fanfare. Comparing Eakins’ Between Rounds (1898), Taking the Count (1899), and Salutat (1898) to Bellows’ Fight Night (1907), Stag at Sharkey’s (1908), and Both Members of this Club (1909) highlights their personal styles and the dramatic shifts occurring in American art at the turn of the century. What do these paintings have in common? How are they different?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers for how the paintings are similar: Both paintings use realism to depict a rich narrative. Both painting explore characteristics of vigorous masculinity through a direct recording of a boxing match.

Possible answers for how the paintings are different: While Eakins focuses on the ceremonies around a match, Bellows focuses on the fight’s fury and physical interaction. He fixates on the strain and the drama, while Eakins adopts a more cerebral, psychological focus. Bellows compresses the fight scene with an intense black background that is further energized by a tightly packed crowd. Eakins depicts a brightly lit expansive environment that is full of genteel spectators. He offers portraits of specific well-heeled individuals, while Bellows’ spectators are a roiling mass, a generalized working class crowd. Bellows touch is gestural and energetic, while Eakins touch is as disciplined as his characters are posed. While both artists use realism, Eakins’ style is more scientific while Bellows’ is more expressive. He doesn’t take a distant aloof view point, rather he is interacting with the crowd as he looks up at the fighters.)

How composition and brushwork accentuate drama

Point out and discuss: How does Bellows’ composition and brushwork accentuate the energy and drama of the fight?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: A stable triangular composition frames the fighters and organizes the scene’s dynamic energy. Note how the left fighters leg and back create one side of the triangle, the back of the fighter on the right and the referee’s arm create the other side of the triangle, and the canvas and spectators serve as the base. Smaller triangles, such as the fighter’s legs, organize and accentuate the fighters’ features. The black background silhouettes the fighters, further highlighting them and pushing them closer to the viewer. Deep shadows heighten the sense of drama. Bellows applies the paint in thick slashing gestural brush strokes that create a visual energy. This accentuates the muscular twisting and torquing of the their bodies. Rapid blurry brushstrokes throughout the canvas evoke energy and motion. He applies the paint wet, causing it to blend and streak like the blood and sweat that drips off the fighters. )

Compare media

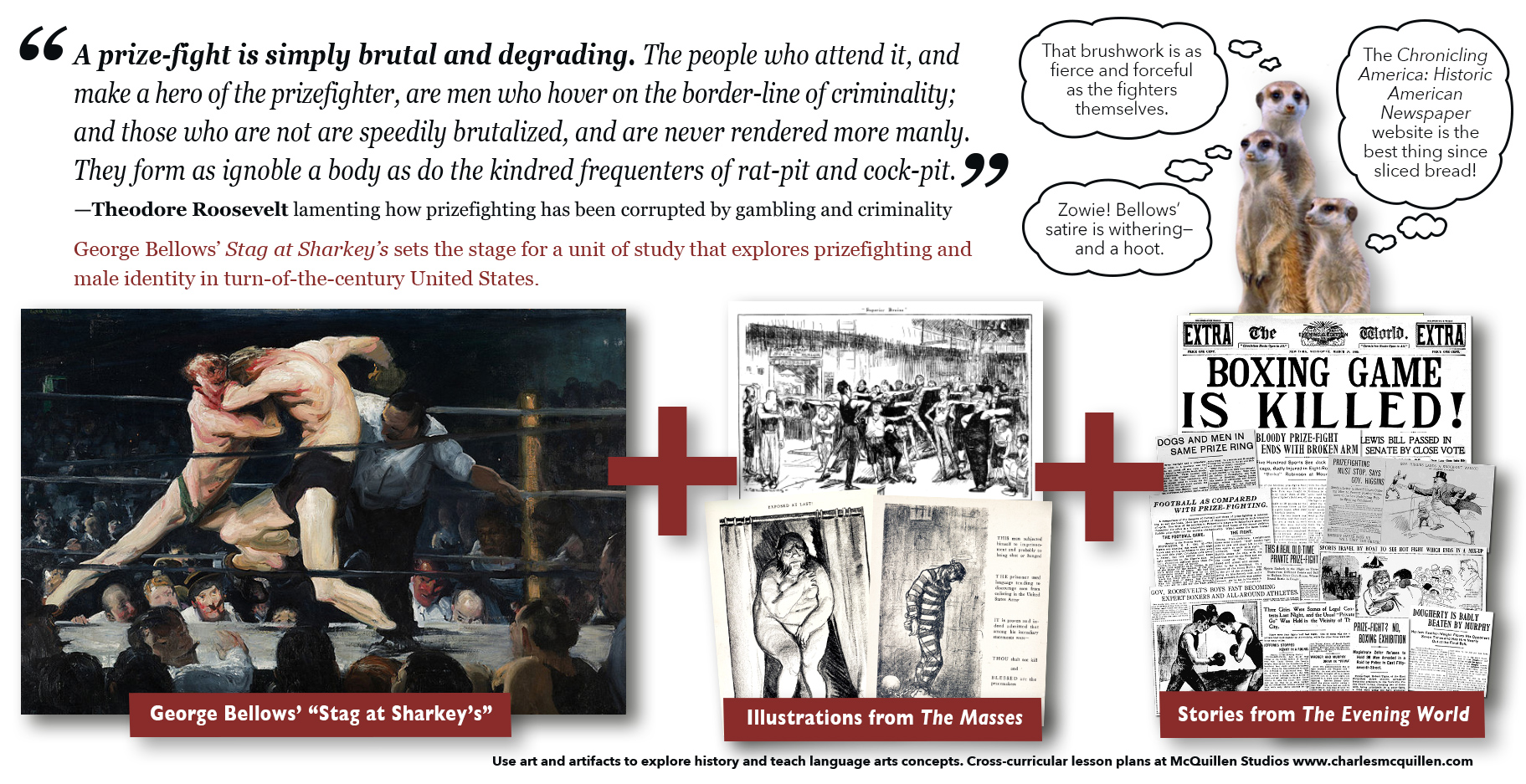

Point out and discuss: George Bellows was a frequent contributor to The Masses, a graphically innovative monthly magazine that advanced socialist causes. Its manifesto read in part:

…a revolutionary and not a reform magazine; a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable; frank; arrogant; impertinent; searching for true causes; a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found;…

Unlike his other magazine artworks that were commissioned to illustrate someone else’s text, these images stood on their own and included his own wording. Known for his sense of humor, Bellows satirical drawings were both funny and biting. He especially directed his satirical ire at the hyper privileged ruling elite and religious hypocrites.

Click on an image to enlarge. Consider who Bellows is satirizing and how he is making fun of them? How are these illustrations different than Bellows’ boxing paintings and what do they have in common?

- “The Business Men’s Class” (The Masses, IV, 7, p10, 1913) Bellows’ early days living at the YMCA introduced him to an assortment of characters and social situations that piqued his sarcastic whimsy.

- “Jury Duty” (The Masses, VI, 7, p10, 1915) While he was elected to the National Academy, Bellows bristled at the elite jury system that only advanced likeminded artists. See his essay An Ideal Exhibition below. During this time, women were fighting for the vote and the right to serve on legal juries so this could have a broader reading.

- “The Nude Is Repulsive to this Man” (The Masses, VI, 9, p13, 1915) In 1873, the anti-obscenity activist Anthony Comstock, with the support of the YMCA, established the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. He also help pass the Comstock Act, the first federal anti-obscenity law that made it illegal to send obscene materials through the mail. As an honorary U.S. postal inspector, Comstock’s legal authority bolstered his standing as a moral arbiter. While originally focused on commercial pornography, Comstock’s purview extended to anything that opened the door to lewd or lascivious behavior, including contraceptives, belly dancing, romance novels, and anatomy textbooks. In 1906 he even raided the Art Students League of New York and confiscated promotional materials that included images from life drawing classes. These rigid interpretations made Comstock ripe for Bellows’ satire. Bellows’ sensitivity may have been heightened by his wife and sister-in-law, who both advocated for women’s rights. For more, see Comstock’s Morals versus Art.

- “Blessed are the Peacemakers” (The Masses, IX, 9, p4, 1917) Like many in the United States, Bellows was conflicted about entering WWI. Soon after making this antiwar illustration, Bellows adopted a more interventionist stance in his essay The Big Idea. See below in quotes. I like how a stone in the wall becomes a halo over the head of the imprisoned conscientious objector who looks like Jesus.

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers for how the illustrations are different than the paintings: The illustrations are satirical, their intentions are clear and straightforward. They are understood on an intellectual level, while the paintings engender an emotional response. The paintings are more expressive and open to interpretation. The captions on the illustrations are critical in meaning making. The titles of the paintings are secondary to the art and are more descriptive than didactic. (The title Stag at Sharkey’s and Fight Night were initially transposed between the two paintings.) While the title Both Members of this Club is meaningful, it inspires interpretation, not biting sarcasm. In the paintings the artist’s touch is meaningful and expressive as Bellows seems to paint with his fists in jabbing strokes. In the mass-produced illustrations the artists touch is uniform and functional.

Possible answers for what the illustrations and paintings share: Both art forms reflect Bellows sympathies for the working class and his view of masculinity, though he does it from different perspectives. The illustrations mock the effete and elite, while the paintings bask in a working class atmosphere. The men in the illustrations are shown as dandies. They stand akilter with frivolous mannerisms, their hands on their hips. The businessmen appear clumsy, awkward, and out of shape while they adopt ballerina-like poses. In contrast, the muscular fighters are depicted as powerful and fierce. The paintings celebrate brawn, fortitude, perseverance, and toughness, while the illustrations mock men who aspire to, but are devoid of these characteristics.)

Here are some additional illustrations from The Masses that highlight Bellows’ mocking wit and sympathies for the working class.

- Why Don’t They Go to the Country for a Vacation (The Masses, IV, 11, p4, 1913)

- Splinter Beach (The Masses, IV, 10, p10, 1913)

- Benediction in Georgia (The Masses, IX, 7, p22, 1917)

- YMCA Sport (The Masses, VIII, 4, p4, 1916)

Think Like an Artist

Identify a Bellowsesque sports picture. With the advances in sports photography over the past 100 years it is easy to overlook the visual significance of Stag at Sharkey’s. When you look at this painting through the eyes of an artist who seeks to depict an equally dynamic sports scene, you start to realize some of the painting’s unique qualities.

- The height of physical exertion for both competitors. In sports such as tennis, the opponent momentarily relaxes as they await their opponent’s play. In addition, opponents are usually a distance apart. It is no small challenge to capture that pregnant moment when both athletes show the intensity of full exertion and the victor is in doubt.

- Spectator reactions. Bellows carefully incorporated spectators into his boxing paintings and illustrations. He appreciated how spectator reactions, with their unbridled emotions, heighten the human drama in a sport’s picture. For many sports, spectators are too distant to be included. In sports like hockey however, the athlete and spectator seem to celebrate together. The fans’ delayed reaction to a winning goal or athletic accomplishment further complicates capturing a golden moment.

- Competitors’ muscle action. Bellows liked the way boxing showed off the fighter’s muscles. Sports such as boxing, wrestling, gymnastics, and swimming showcase the human form. While Bellows appreciated the ferocious competition of football and sketched football players, he felt the uniforms and padding obscured their muscle movement.

- A composition that organizes the dynamic parts into a unified whole. This is not just the purview of a painter with the luxury of time to plan. Photographers who know their sport and anticipate typical angles of attack can make a fleeting moment more powerful with a coherent composition.

Sift through sports photographs and see how many have these four characteristics. Share your favorite sports photographs and consider which of these characteristics is most common and which is most valuable. Better yet, try capturing these characteristics in your own sports photograph.

Life Lesson

Be expansively exploratory and narrowly focused.

The first thing a student should learn, is that all education that amounts to anything is self-education. Teachers, college, books—these are only the opportunity for education. They are not in themselves education.…You do not know what you are able to do until you try. In learning a topic, whether it be painting, or housekeeping, or building, or any other art, consider every method that can be followed. Try it in every possible way. Be deliberate. Be spontaneous. Be thoughtful and painstaking. Be abandoned and impulsive, intellectual and inspired, calm and temperamental. Learn your own possibilities. Have confidence in your self-reliance!

—George Bellows describing his opposition to conformity in “The Relation of Art to Everyday Things: An Interview with George Bellows on How Art Affects the General Wayfarer,” Arts & Decoration, Vol. 15 No. 3, July, 1921, pages 158–159, 202. (also below in the quote section)

When you consider the broad range of subjects, styles, and influences Bellows’ work encompassed, it is clear that when it came to art he practiced what he preached. There wasn’t anything he wouldn’t try when it came to his art. The inverse was also true. There wasn’t anything he would do if it interfered with his art “self-education.” Bellows left Ohio State University just weeks before final exams his junior year under the belief that the faculty had no more to teach him about art. Even though the Cincinnati Reds recruited him, offering him much needed revenue, he turned his back on that opportunity as well. Instead, he went to New York City, rented a room at the local YMCA, scrimped by on a meager allowance, all so he could attend New York School of Art and learn how to paint. In his book Creativity: The Psychology of Discovery and Invention, Mihaly Csikzentmihalyi contends that, “Among the traits that define a creative person are two somewhat opposing tendencies: a great deal of curiosity and openness on the one hand, and an almost obsessive perseverance on the other. Both of these have to be present for a person to have fresh ideas and then to make them prevail.” (page 326) When it came to art making, Bellows was expansively exploratory and narrowly focused. In a world full of ready distractions, that is easier said than done. Creative self-education may be fulfilling, but it ain’t easy.

Related Videos

- George Bellows Part I (20:42) by the National Gallery of Art is a must-see documentary that uses historical photographs and film footage with Bellows’ art to show the world that shaped his work.

- The Boxing Illustrations of George Bellows (4:12) by the Cleveland Museum of Art offers a detailed analysis of Stag at Sharkey’s and other boxing illustrations by Bellows.

- The Art of Boxing: George Bellows at the National Gallery, Washington (4:05) examines Bellows’ four boxing canvasses ―Club Night (1907), Stag at Sharkey’s (1909), Both Members of This Club (1909), and Dempsey and Firpo (1924)—through the eyes of Sharmbá Mitchell, a former boxing champion, and Charles Brock, associate curator of American and British paintings.

Integrating into Your Curriculum

Artists oftentimes use common visual strategies or signposts to alert viewers to significant details in their art. Here are some ideas for using these visual signposts to unpack a work of art. Remember, the close reading skills in art appreciation are similar to the close reading practices taught in reading. This video models how this painting can be used to cultivate cross-curricular learning.

Literature Links: What piece of literature would you partner with George Bellow’s Stag at Sharkey’s?

Industrialization and Immigration: America’s industrial centers were transformed by and transformed their burgeoning immigrant populations. Like many writers from his time, George Bellows found artistic inspiration in the brutality and courageousness of this transformation.

- O. Henry’s (William Sydney Porter) The Duel (1902?) is a short story about how New York City transforms a businessman and an artist after they arrive from the Midwest.

- John Dos Passos’ Manhattan Transfer (1925) profiles the lives of New Yorkers at the turn of the 20th century honing in on their unrequited love, disintegrating relationships, broken dreams, and creeping desperation.

- Upton Sinclair’s novel The Jungle (1906) exposes the oppressive conditions Chicago’s meatpacking industry imposed on its workers in the early 1900s.

- Thomas Bell’s Out of This Furnace (1941) examines the inhuman working conditions and the rise of trade unions in Pittsburgh’s steel mills over three generations from the 1880s to the 1930s.

Prizefighting: Like Bellows’ painting, these writings focus on prizefighting, as opposed to the more regulated boxing.

- Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Rodney Stone is a coming of age story against the backdrop of bare-knuckle prizefighting. (The story takes place in Great Britain, not the United States, but the guy wrote Sherlock Holmes so he gets included.)

- Jack London’s A Piece of Steak was originally published in 1909 in the Saturday Evening Post, the same year Bellows painted Stag at Sharkey’s and Both Members of This Club. This short story about an aging prizefighter, Tom King, pits experience against youth, Pronto Sandel. While focused almost exclusively on the fight itself, great writing and an inner monologue explore themes of poverty and inevitable decline. In this sentence Tom studies the veins that pump blood into his battered hands and contemplates his diminishing endurance.

No longer could he do a fast twenty rounds, hammer and tongs, fight, fight, fight, from gong to gong, with fierce rally on top of fierce rally, beaten to the ropes and in turn beating his opponent to the ropes, and rallying fiercest and fastest of all in that last, twentieth round, with the house on its feet and yelling, himself rushing, striking, ducking, raining showers of blows upon showers of blows and receiving showers of blows in return, and all the time the heart faithfully pumping the surging blood through the adequate veins.

- Jack London’s The Mexican (1911) is another short story that revolves around a prizefight. This time a Mexican enters the ring to fight to raise money for the Revolution at home and stand against racism in the United States.

- Jack London’s The Game is a novel about a prizefighter who dies in the ring the night before he gets married.

- Theodore Roosevelt’s “The Recent Prize Fight” (The Outlook, July 16, 1910, page 550) is an essay that disparages the criminality and racism that corrupt this once proud manly sport.

- Hamilton Fyfe’s “What the Prize-Fight Taught Me” (The Outlook, August 13, 1910, page 827) is an essay on the corruption of prizefighting that offers food for thought for contemporary sports fans.

- Jack London’s The Abysmal Brute (1911), a novelette plot outline bought from Sinclair Lewis, explores fight fixing.

- C. Moise’s “The Last Ounce: The Story of a Prize-fight” (The American Magazine, April, 1913, Vol 75, pages 70–79) with four illustrations by George Bellows, recounts the comeback fight of Jimmy Nolan as he struggles to regain his title, reputation, and self-esteem in a grueling 13-round bout that required his final ounce of energy.

- Jonathan Brooks’ “Chins of the Fathers” (Collier’s, 1924, vol 73, pgs 14–15 and 32–33) is a sentimental short story about a young boxer who fights more than just his opponents when he enters the ring. A prominent Bellows’ illustration makes this worthy of inclusion here.

- Ernest Hemingway’s Prizefight Women published in the Toronto Star Weekly, May 15, 1920, describes a night of fighting witnessed by a new audience—women. While written when Hemingway was just 21, this article offers a glimpse at the economical writing style and machismo that would characterize his later works.

As the gong rang the craggy-faced slugger shot out of his corner. The dub made an awkward attempt to put up his hands. The slugger swung his right fist in a deadly semicircle to the dub’s jaw, and the fight was over. The fat, untrained dub crashed on his face on the resined canvas. When his seconds pulled him over to his corner, the canvas had sand-papered most of the skin off one side of his face.

Writing Opportunity: Inquiry-based research and writing

O. Henry (William Sydney Porter) introduces New York City and the protagonists in his short story The Duel with the following lines

But every man Jack when he first sets foot on the stones of Manhattan has got to fight. He has got to fight at once until either he or his adversary wins. There is no resting between rounds, for there are no rounds. It is slugging from the first. It is a fight to a finish.…

They came out of the West together, where they had been friends. They came to dig their fortunes out of the big city. Father Knickerbocker met them at the ferry, giving one a right-hander on the nose and the other an upper-cut with his left, just to let them know that the fight was on. William was for business; Jack was for Art. Both were young and ambitious; so they countered and clinched.

O. Henry and George Bellows both appreciated prizefighting as a sport and as a metaphor. A society’s favored pastimes offer insight into its interests and values. At the turn of the 20th century the sport of boxing was finding its way. In New York City it was transitioning from a blood sport to the sweet science of bruising. Researching this transition provides insight into the world that shaped Bellows’ art and times, and it likewise offers an opportunity to reflect on what our pastimes say about us as a society.

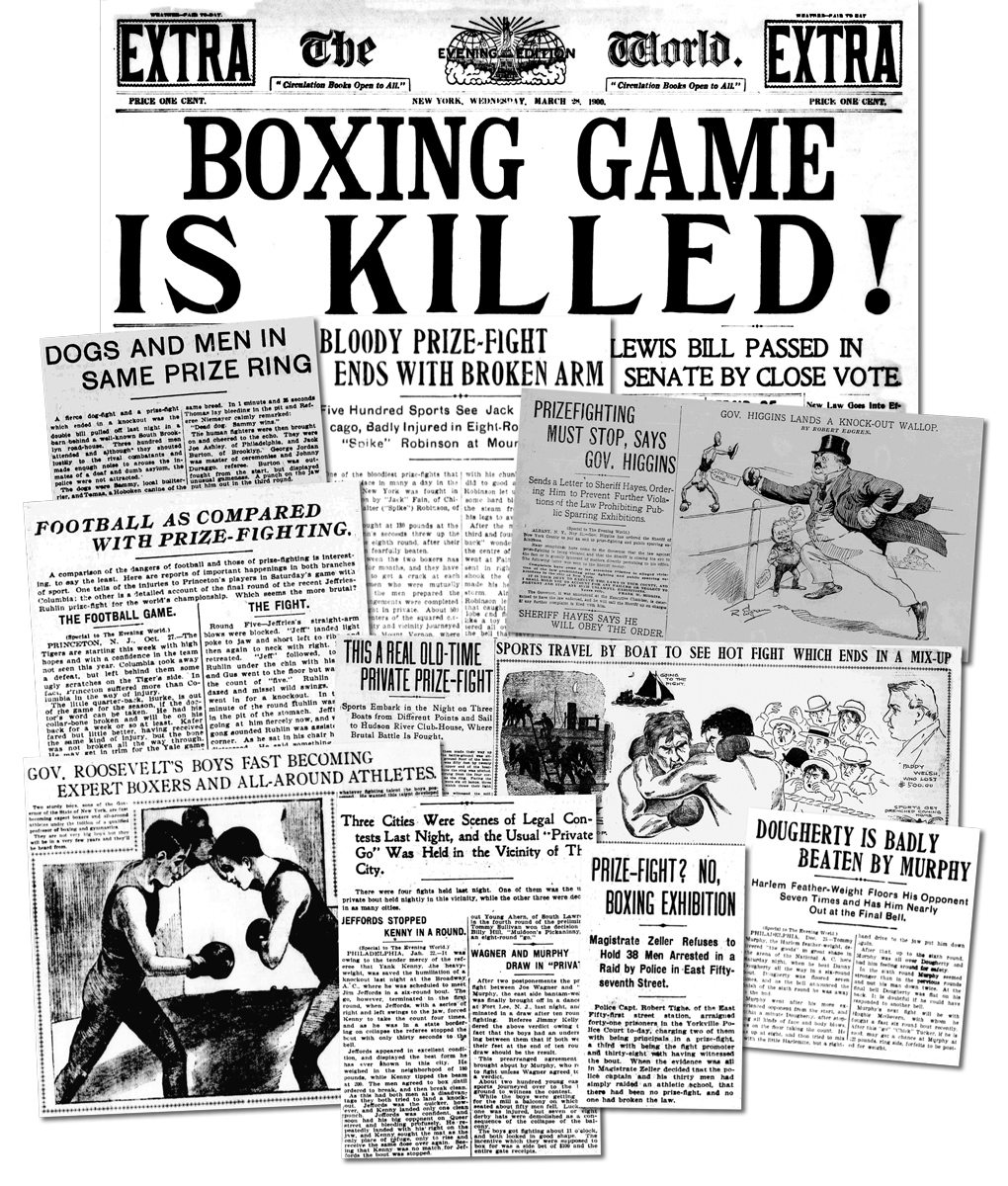

What firsthand resource could students use to research their interests? Joseph Pulitzer’s daily The Evening World catered to New York’s growing immigrant population and pioneered his special brand of sensational “yellow journalism.” This daily introduced a sports section just as boxing was being outlawed in New York and clandestine prizefighting stags became the rage, the same fights that inspired Bellows’ Stag at Starkey’s. The daily’s gripping accounts, comical illustrations, and over-the-top advertisements make for fun and insightful reading and research.

How will students access these old sports sections? Wait for it. Wait for it. Voila, the Library of Congress to the rescue. Their fantastic Chronicling America Historic American Newspaper site is an awesome educational resource and makes me proud that my tax dollars were spent so well. It is staggering how accessible and comprehensive this research base is. If students want to sift through the newspapers, then I recommend the advanced search function and narrow your search parameters to ”prize-fight” or “boxing” between the years 1900–1920. Even with that you will be overwhelmed with the offerings so further limit the search to the newspaper “The Evening World (New York, N.Y.)”

How will students access these old sports sections? Wait for it. Wait for it. Voila, the Library of Congress to the rescue. Their fantastic Chronicling America Historic American Newspaper site is an awesome educational resource and makes me proud that my tax dollars were spent so well. It is staggering how accessible and comprehensive this research base is. If students want to sift through the newspapers, then I recommend the advanced search function and narrow your search parameters to ”prize-fight” or “boxing” between the years 1900–1920. Even with that you will be overwhelmed with the offerings so further limit the search to the newspaper “The Evening World (New York, N.Y.)”

The news stories below are organized around some common themes. Have students read stories that interest them and share what they have learned. As historical artifacts, these articles also offer students opportunities to read for point of view and explore values. Have students note especially how these articles and the neighboring advertisements define masculinity.

The Question Formulation Technique (QFT) can help turn art observations and wonderings into inquiry-based research questions that build on student insights and interests. For ideas on how to structure inquiry circle see Stefanie Harvey and Smokey Daniels Comprehension and Collaboration: Inquiry Circles for Curiosity, Engagement, and Understanding. Matt Horgan’s Blood Sport in Pittsburgh: An Analysis of Prize Fighting and Cock Fighting in an American Industrial City models how to use newspaper accounts about prizefighting to write a research paper that explore societal trends in turn-of-the-century United States.

One way to rally this research into a creative class project is to simulate a sports page around the events in Stag at Sharkey’s. This could include a descriptive story about the fight; dialogue-rich interviews with the fighters, referee, Tom Sharkey, or members of the crowd; editorials condemning or promoting prize-fighting; spoof advertisement that address male ailments; and illustrations or cartoons. Here is a gallery of telling articles. Click on an image for a closer look.

General

- “Eddie Hanlon Wins Fierce Fight from Broad in the Fourteenth Round,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 30 Jan. 1904, page 4. This sports page is chock full of fight news and is an ideal shared text for exploring the landscape of turn-of-the-century boxing. It reflects the widespread prestige of the sport. In one story a police raid breaks up a “private club fight” in New York. In another story racism plays a role in an unjust decision in Chicago. Masculinity is defined by the advertisements and news accounts.

Brutality and Savagery

The law banning boxing drove prizefighting underground, exacerbating the very corruption and brutality they hoped to squelch.

- “Football as Compared with Prize-Fighting,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 27 Oct. 1902, page 8. Comparing the injuries from a Princeton-Columbia football game with those from the Jeffries-Ruhlin fight links the sports—and our times. Note the small neighboring story on a fatal concussion suffered during a football game. Does football have the same atavistic allure as prizefighting did and will it fade from the headlines as boxing has?

- “Dogs and Men in the Same Prize Ring,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 18 Sept. 1903, page 10. Sweet science of bruising or blood sport? This article offers evidence to the latter. Note the neighboring story on a questionable decision and the medical advertisement promising to “cure men.” A lot of themes here wrapped up in one sports page.

- “Bloody Prize-Fight Ends with Broken Arm,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 26 Dec. 1904, page 5. This detailed description of a brutal eight round fight lets you join 400+ sporstmen who “went to see a bloodthirsty battle, and every mother’s son of them went home perfectly satisfied.”

- “Roosevelt Will Probe Fatal Bout,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 08 Nov. 1905, page 7. A grudge fight between midshipmen results in death and lands on President Roosevelt’s desk for investigation.

Gambling and Criminality

- “This a Real Old-Time Private Prize-Fight,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 22 June 1904. Under the cover of darkness three boats ferried fight fans and gamblers to a boat house for a match that ended in biting.

- “Prize Fighters Freed by Court,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 16 Jan. 1905, page 8. While a police raid is unable to distinguish a prizefight from a boxing exhibition, they do net several hidden revolvers.

- “Prize-Fight by Daylight in the Heart of the Financial District,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 06 April 1907, page 1. A clandestine gathering of 50 stockbrokers and businessmen gathered to watch and wager on a mid-day bout between Willie Mango and Emergency Kelly.

Political and Legal Hurdles

In 1900, the Lewis Law essentially outlawed prizefighting, except for fistic exhibitions in private boxing clubs. This loophole spawned illicit “fight clubs” where attendees paid membership dues instead of admission fees. The police and courts struggled to distinguish illegal prizefights from private boxing exhibitions. Partisan political infighting likewise informed the debate.

- “An Early Death for the Boxing Game,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 17 April 1900, page 8. The impending enactment of the Lewis Bill inspires boxing clubs and causes contenders to scurry to get their bouts in under the wire.

- “Boxing Game Is Killed,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 28 March 1900, pages 1 and 7. This headline grabbing news account describes the provisions of the Lewis Boxing Bill that banned professional boxing.

- “Three Cities Were Scenes of Legal Contests Last Night, and the Usual ‘Private Go’ was held in the Vicinity of this City,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 22 Jan. 1904. The absurdity around the fight club loophole induced as much hilarity in the press as it did consternation in the courts.

- “Senator Frawley Referee at this Prize Fight,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 22 April 1904. The New York State Senator who would eventually lead the effort to legalize boxing referees a club bout—and then denied it when approached by a reporter. The through-the-window exchange with the reporter is amusing considering the role he would eventually play in the sport.

- “Prizefighting Must Stop, Says Gov. Higgins,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 31 May 1906. Page 1. Efforts to prosecute an illegal prizefight unearth a private meeting of a wildly exuberant boxing club, or at least that is what the participants argue.

- “Boxing Game Knocked Out by Ruling of the Court,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 11 June 1906, page 1 and 2. Prizefight participants argue they box at night for exercise and pay regular club dues, not admissions fees.

- “Frawley Law May Mean Return of Old Days When Fortunes were Spent on Ring Battles,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 29 July 1911, page 6. Debate swirls on whether the boxing game will still be as lucrative with the Frawley bill’s new regulations.

- “Boxing Now Legalized in New York State,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 26 July 1911, page 8. While the boxing debate will continue in the statehouse, boxing is once again legalized and 10-round bouts are permitted in halls or open-air arenas like race tracks.

- “Commission Expects to Put Boxing on the Highest Plane,” The Evening world. (New York, N.Y.), 30 March 1912, page 6. Boxing supervisors plan further changes in rules that should give boxing the same standing as baseball.

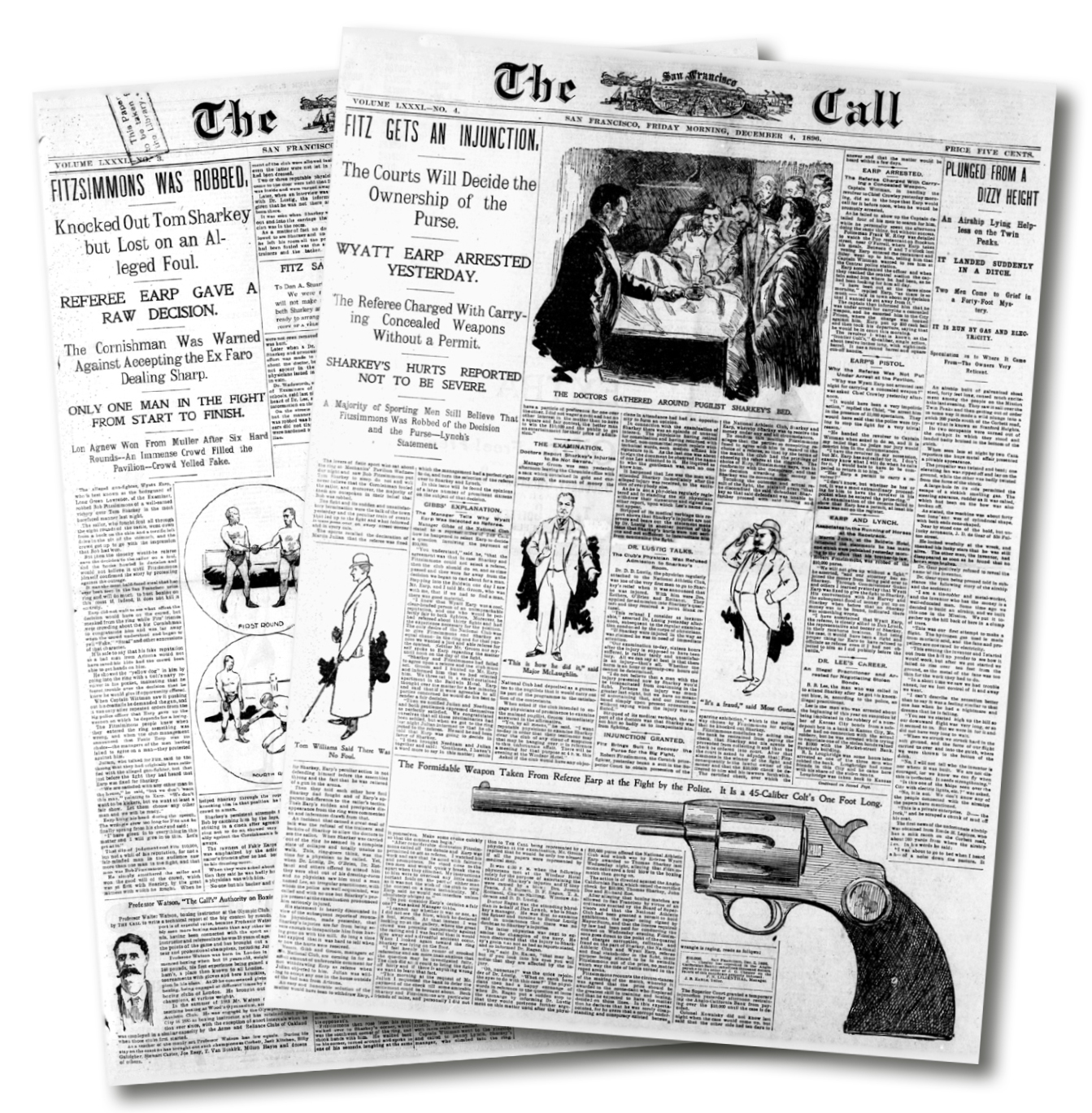

“Sailor” Tom Sharkey

In addition to being the proprietor of the bar/fight club that Bellows frequented for some of his most famous boxing painting, Tom Sharkey was also a heavy weight contender. His career as a fighter and promoter is especially colorful and touches on the common themes explored here—brutality, criminality, finding a way out of poverty through fighting.

In addition to being the proprietor of the bar/fight club that Bellows frequented for some of his most famous boxing painting, Tom Sharkey was also a heavy weight contender. His career as a fighter and promoter is especially colorful and touches on the common themes explored here—brutality, criminality, finding a way out of poverty through fighting.

- “Fitzsimmons Was Robbed, Knocked Out Tom Sharkey but Lost on an Alleged Foul,” The San Francisco Call. (San Francisco [Calif.]), 03 Dec. 1896, Page 1. In his bout against Fitzsimmons, Sharkey gets knocked out but wins on a raw decision by referee Wyatt Earp. Yes, that Wyatt Earp, the gambler, buffalo hunter, gun fighter, and lawman who took part in the gunfight at the O.K. Corral. Was the fix in?

- “Fitz Gets An Injunction,” The San Francisco Call. (San Francisco [Calif.]), 04 Dec. 1896, page 1. As the dust settles from the Sharkey-Fitzsimmons bout, the list of misdeeds and skullduggery mount.

- “Jeffries the Victor,” The Sun. (New York [N.Y.]), 04 Nov. 1899, page 1. In a hard fought 25-round bout, Sharkey and Jeffries created a boxing classic. Sharkey suffered a broken nose, two broken ribs, and a horribly swollen ear.

- The Bioscope Festival of Lost Films shows a recreated excerpt of the 25-round, 2 hour fight between “Sailor” Tom Sharkey and Jim Jeffries, the last great fight of the 1800’s and the first match filmed.

- “Fitzsimmons and Sharkey Matched,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 05 March 1900, page 8. A news story recounts the planning of a 25-round winner-take-all boxing match. Neighboring articles describe Teddy Roosevelt’s sons’ boxing prowess.

- “Advance Report of To-night’s Fight, Round by Round, By Thomas Sharkey,” The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 30 Aug. 1900, page 2. Based on his experience fighting both men, “Sailor” Tom predicts the outcome of a big fight the night before the Lewis Law takes effect.

Male Identity / Masculine Ideals

These sports pages are rich with opportunities to explore turn-of-the-century views of masculinity. As students read, have them note references to the hyper-masculine ideals espoused on the sports pages and that Teddy Roosevelt carefully cultivated for his own public image—strength, stamina, toughness, fortitude, self-sufficiency, aggressive, confident, rugged, brash, charismatic, virile, courageous, honorable, independent, and heroic. While these fighters typically existed in exclusively male environments, there are articles about their wives and girlfriends that further highlight gender roles and ideals.

How would you use this painting to build on one of your units of study? Please share if you have other ideas on how to teach Stag at Sharkey’s by George Bellows as an English/language arts lesson plan.

Click this link for a lesson that pairs Jack London’s A Piece of Steak with George Bellows’ Stag at Sharkey’s to teach writers expressive word choice and sentence structure.

On boxing

- Before I married and became semi-respectable, I lived on Broadway opposite the Sharkey Athletic Club where it was possible under the law to become a ‘member’ and see the fights for a price.

- I don’t know anything about boxing. I am just painting two men trying to kill each other.

- Who cares what a prize fighter looks like? It’s his muscles that count.

- I do not care about the expression of the prize fighters mug. A prize fighter’s muscles are his e pluribus unum. The expression on his face is about as important as the polish on a locomotive’s headlight…Prize fighters and swimmers are the only types whose muscular action can be painted in the nude legitimately.

- I am not interested in the morality of prize fighting. But let me say that the atmosphere around the fighters is a lot more immoral than the fighters themselves.

- A fight, particularly under night light, is of all sports the most classically picturesque. It is the only instance in everyday life where the nude figure is displayed.

- Prizefighters and swimmers are the only types whose muscular action can be painted in the nude legitimately.

- All sport is cruel. For one side’s victory presupposes the other side’s defeat. But in baseball or football, where the game covers a large area and the play is diffused, it is difficult to focus a point in the game that tells the story. In a prize fight interest centers on the two men. There is effective drama in its big moment of victory and defeat. And I have the average man’s interest in all sports.

On art and art making

- Art must tell a story.

- Every artist is looking for news. He is a great reporter of life, keeping his eyes open for some hitherto untold piece of reality to put on his canvas. His picture chooses him. He doesn’t choose what he shall paint anymore than a writer chooses the news that shall happen or the idea that shall possess him.

- It is a matter of feeling. The test of my success with a picture, to me, is whether I have been able to make other people feel from the picture what I felt from the reality.

- The ideal artist is he who knows everything, feels everything, experiences everything, and retains his experience in a spirit of wonder and feeds upon it with creative lust.

- The artist is the person who makes life more interesting or beautiful, more understandable or mysterious, or probably, in the best sense, more wonderful.

- The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance.

- Art strives for structure, and aspires for magnificence.

- I can’t see anything in the worship of beauty which some people seek to develop. Beauty is easy to paint; just as easy as something grotesque. What really counts is interest.

- Lacking choice art dies.

- According to my view, drawing and painting is a language. You can be great or small, glad or sad, in its use according to what you have to say.

- To be a student is to have an eternal aptitude of mind for the assimilation of understanding, impressions, and knowledge.

- Every student must become at once editor and judge of who and what is for him worthwhile.

- Many painters specialize these days. It’s all wrong. If a man can paint at all he can paint anything that he knows or feels.

- I expect to change my methods entirely when I learn what I can in a new direction.

- I admire the man who tries to do a big thing with the implements at his hand. Even if he fails to please, he has done something worthwhile.

- Learning to draw or paint is comparatively an easy matter. But to say anything—you must have ideas. You can paint perfectly and still be as uninteresting as a college professor giving a dry lecture.

- A great school is where a great teacher is.

- A work of art may be described as an arrangement or ordering of forces with the motive of stimulating the emotions and the receptivity of the mind to aesthetic impression and creation.

The Big Idea: George Bellows talks about Patriotism for Beauty

“I am a patriot for beauty” is George Bellows’ idea. “I would enlist in any army to make the world more beautiful. I would go to war for an ideal—far more easily than I could for a country. Democracy is an idea to me, is the Big Idea. I cannot believe that democracy can be dropped out of existence because of the purpose of one or of many nations.

“I am going out to California this summer and paint my head off—and then I’ll do my stunt for democracy—if it comes out that way. I cannot put my finger on my war psychology at all. I can see clearly the beauty of France giving her blood for the ideal expressed in “Ma Patrie.” But then, too, I can see the point of view of the Pacifist who wants to lead his life in his own way, out to the end he has planned for it, and who wants to work for his children and stay with them. But where the Patriot gets it over the Pacifist in my mind is that he does not have a chance to be a coward. And the Pacifist can be either a philosopher or coward as his nature suggests—that is what troubles me about it.

“I hate the thought of fighting—but I am all for democracy. You see it tangles a fellow up pretty badly. I guess most men I know would feel mighty sick at the thought of a bayonet. To me the bayonet is the worst part of war. And yet back of the bayonet is the great call to democracy.

“I have been called a revolutionist—if I am, I don’t know it. First of all I am a painter, and a painter gets hold of life—gets hold of something real, of many real things. That makes him think, and if he thinks out loud he is called a revolutionist. I guess that is about the size of it.

“I am deeply interested in real life. I want to see it, I want to paint it, and God knows I do not want to destroy it. But there you are. If you think, you see democracy looming large for the whole world; France is great because she is living it, Russia is great because she is starting it. If you think, you know democracy has got to win— not in this nation or in that, but freedom for the whole world. ‘

“I have always felt about art, that it was freedom that counted. A man must see things and say things his own way. This is his New Imagination. No artist who thinks can spend his life trying to understand another man’s interest. It’s all right about those wise old guys in Italy and Spain. I am mighty interested in what they did, because they used their own imagination for their lives. And I want to use mine for the things I see—the Hudson, the skyscrapers, the sea at Monhegan, ship-building at Gloucester, I see wonder where the young immigrants play in the green river parks at night.

“I like to paint Billy Sunday, not because I like him, but because I want to show the world what I do think of him. Do you know, I believe Billy Sunday is the worst thing that ever happened to America? He is death to imagination, to spirituality, to art. Billy Sunday is Prussianism personified. His whole purpose is to force authority against beauty. He is against freedom, he wants a religious autocracy, he is such a reactionary that he makes me an anarchist. You can see why I like to paint him and his devastating ‘saw-dust-trail.’ I want people to understand him. “When I paint the great beginning of a ship at Gloucester, I feel the reverence the ship-builder has for his handiwork. He is creating something splendid, to master wind and wave, something as fine and powerful as Nature’s own forces. I get it from him that he is impressed with his own struggle to accomplish this, and when I paint the colossal frame of the skeleton of his ship I want to put his wonder and his power into my canvas, and I love to do it. I have no criticism to make of what he does, I am filled with awe, and I am trying to paint as well as he builds, to paint my emotion about him. I call this the ‘New Imagination’—I have no other.

“I tried to do something as genuine as the painting of a shipbuilder’s work when I painted a famous old man for a famous New York club house. I put my kind of imagination into it. I wanted to make him live just as he was. It seemed to me that if the club members wanted him to be painted, they would want him as they knew him. And then I made a canvas with the color that belonged to life, full of it, but the art committee of the club sent my picture back. And now I am very glad of it. I like it around, because it has come to be regarded as the best portrait I ever have painted.

“It’s a queer thing about models. Do you know some people have the design of a painting in their features and bodies, and some haven’t. I have seen beautiful women whom you couldn’t paint at all, you couldn’t get a design from them, you couldn’t make their bodies compose. And along comes a little girl, not especially pretty, not striking, but you can paint her; she can make designs for a dozen paintings.

“ I am always very amused with people who talk about lack of subjects for painting. The great difficulty is that you cannot stop to sort them out enough. Wherever you go, they are waiting for you. The men of the docks, the children at the river edge, polo crowds, prizefights, summer evening and romance, village folk, young people, old people, the beautiful, the ugly. Everywhere the difficulty that I have had, even when I was quite young was to stop long enough to do the thing. As a student I was always eager to do the tremendous, vital things that pressed all about me. It seems to me that an artist must be a spectator of life; a reverential, enthusiastic, emotional spectator, and then the great dramas of human nature will surge through his mind.

“I do not see why a man should wait a minute to begin work after he has any security in his technique; because the way to become a painter is to paint. There are only three things demanded of a painter: to see things, to feel them, and to dope them out for the public. You can learn more in painting one street scene than in six months’ work in an atelier. My advice is to paint just as soon as you have the confidence to, and keep your ideals of art aloof to criticize your painting with. Watch all good art, and accept none as a standard for yourself. Think with all the world, and work alone.

“When once you begin to work, it is amazing how people account for what you accomplish. I have been told in print that I have found my inspiration in Spain with Goya; in France with Manet and Courbet; in America with artists younger than myself, and from whom I could not have gained help because my painting began before theirs. I have been said to have come out into the painting world slowly, handicapped with my respect of old masters. I have been accused of painting without reverence for art before I had mastered my technique. It seems to me the only way is to get from the past what you can, from the present what you are bound to, to absorb it all, assimilate what you can; think, see, feel, live and work. Anyway, the great purpose of art is to develop the artist, the pleasure that he gives is secondary. If he has many big ideas and fine ideals and a technique to put them over, so much the better; but in the main, art is man’s capacity of showing his development. And every artist must do it his own way.”

We feel that Mr. Bellows has given us a very good recipe for being a painter, “watch all good art and accept none as a standard, think with all the world and work alone.” The man who can do this will indeed find his own development. He will understand what has been done the world over, appreciate it, assimilate it and forget it. There is truly no more individual young painter in America today than George Bellows, no more sincere student of art and no more genuine admirer of what has been done in art throughout the world. But as he says, “every artist must do it his own way”—and we feel that Bellows’ way is a very American one, frank and worthwhile.

—George Bellows’ “The Big Idea: George Bellows talks about Patriotism for Beauty,” The Touchstone, v.1 1917. Pages 269–271.

The Relation of Painting to Architecture: An Interview with George Bellows in Which Certain Characteristics of the Truly Original Artist Are Shown to Have a Vital Relation to the Architect and His Profession

“… I am sick of American buildings like Greek temples and of rich men building Italian homes. It is tiresome and shows a lack of invention. I paint my life . . . All living art is of its own time . . . Few architects seem to grasp this. Bush Terminal Sales Building is expressive of our needs. Greek temples with glass windows are foolish.”

—George Bellows.

In these words is expressed a point of departure and the essence of this interview. We sought George Bellows because we believed he represented that non-conformist attitude toward tradition that most architects unfortunately lack. We talked to him with that belief in mind. It mattered little just what the exact relation of painting, as expressed purely in pieces of canvas or in mural decoration, might have to architecture. It mattered less to attempt any exhaustive or dispassionate inquiry into the niceties of that relation. What did matter was the fact that Mr. Bellows typifies an attitude toward art whereby he is enabled to produce really original work. How he does it is undeniably of interest to architects, and he has frankly given of himself in this interview to place before the architectural profession every helpful experience.

“There is no new thing proposed, relating to my art as a painter of easel pictures, that I will not consider,” stated Mr. Bellows. “The fact that a thing is old and has stood the test of time has become too much a god to almost all men who can be termed artist. What it seems to me should interest the architect is exploration, not adaptation,” he explained. “I have no desire to destroy the past, as some are wrongly inclined to believe. I am deeply moved by the great works of former times, but I refuse to be limited by them. Convention is a very shallow thing. I am perfectly willing to override it, if by so doing I am driving at the possibility of a hidden truth. It seems obvious that architects should have the same attitude toward their work.”

As an example of his attitude toward the conservative acceptance of given ideas, we asked Mr. Bellows what he thought the artist should know about period styles in order more clearly to understand the work of architects. Here is the answer:

“I do not believe in period style. It seems secondhand. All living art is of its own time. Few architects seem to grasp this. Period style is a reversion to past types. Originated styles of the present period would be desirable, and could vary with their locality. There would need to be no monotony. These styles, if they were devised, could be as glowing, as virile, as truly fine as any that we now worship, for they would be of our own time. We would understand them. We could do them better. They would have greater significance to the layman, for they would not be shrouded in mystery and obscure allusion.” Here was our plea for regional types, set forth in all its glory by one quite outside of the architectural profession!

Then, we prompted, what would you suggest to attain that end? “The fault lies in the spirit of the times, which is reflected in the way we educate architectural students,” went on Mr. Bellows. “Schools of architecture teach conventional architecture, period architecture. I do not believe in education as an end, so much as in the opportunity for men of imagination to have opportunity. But your schools of architecture interfere with such an opportunity. If an architect tried to create something independent of “periods” he would have a hard time to place his work. And yet all the possibilities of significant form have not been exhausted, have they?” We had to admit they have not. “Why, then, should architects worship the ‘period’ as they do?” questioned Mr. Bellows. “If there are further significant forms to be originated, and every one agrees that there are, I can see no reason why we are bound to the existing forms and scorn any attempt to create the new, the original.

There are two rather distinct spirits in which a painting is created,” continued Mr. Bellows. “One has a very decided relation to architecture, the other does not necessarily have such a relation. The mural decoration per se is essentially painted for a certain place. Other picture forms are not. In the latter case, which is the infinitely larger of the two classes, an artist may be said to be fundamentally interested in developing an arbitrary space to the profoundest condition of beauty of which he is capable. This cannot be considered, then, as essentially a decoration for a wall, but must be regarded and looked at for itself alone as a thing complete. Almost we might say in the spirit of a book, the color of whose cover is the only relation to the room in which it is placed. An oil painting in particular can only be at its best under a light that gives its exact values and therefore people to whom paintings are precious must take the greatest care to arrange for such conditions. On the other hand, the mural decoration can be created by a master without these limitations affecting his spirit. A profound understanding of space can free the painter from this one genuine limitation. The other limitations, which in our day tend to spoil and make common the mural decoration, are artificial, man-made dogmas and the limiting of the artist from the point of view of subject matter, morality, etc.

“On the other hand, a large percentage of architectural works must be limited by utility. These limitations seem to be even greater for the architect than for the painter in present day life. But these limitations need not prevent an architect from creating beautiful proportions among the utilities in space and texture and color. I feel that the architects themselves have been largely guilty for allowing the fashions of the past to become the fashions of the present. It is really a platitude to say that all living art is of its own time, expressive of the finest spiritual and even material necessities of its own people. It is not the expensive material that counts. But it is the men who sense the proper proportions and understand space itself that make great architects.”

While every artist will agree that a painting may be said to have utility in a certain sense, the utility of a painting is not its essential characteristic, while the utility of a work of architecture is. Thus Mr. Bellows may say that each picture should be thought of for itself specifically, without relation to its surroundings. People speak of pictures in the home as spots of color on the wall. That is not their primary function in Mr. Bellow’s estimation. A painting may be a decoration on the wall, but it is not necessarily so. A picture, as he understands it, is a human document of the artist, and may be as little decorative as a book; the binding may or may not be decorative, but even if it is, the decorative aspect is not the prime function. One looks at etchings frequently in portfolios, isolated from their surroundings. They are beautiful in themselves. The proper attitude, Mr. Bellows maintains, is to consider nothing but the picture, not its proposed environment. If it is right it is right. It is not valueless because one cannot find a good place for it. It is a work of art, anyway.

This, related to architecture, would mean that the architect would create something subjective as “a human document” without relation to the purposes of the structure or its environment. Just what would happen if architects were to dot the landscape with works of art that have no relation to their surroundings is something that affords interesting speculation. Is it better to put a fairly dull, trivial structure in an unimportant locality for the sake of maintaining the present character, or should an architect take it upon himself to alter the character of the neighborhood by the construction of something very fine too fine like a prince among paupers. Here the proprieties war with the impulse to be free of past traditions and to express courageously one’s original ideas and individuality. Should one express oneself frankly despite another’s feelings? Need the architect of originality have his way, and compel the public to view his obtrusive personality as manifested in an overassertive building? Mr. Bellows believes that the artist-architect would be creating a landscape just as a painter creates a landscape he would do what he could to enhance its beauty. What that “what” would be is debatable.

But Mr. Bellows feels insistently that art must be original. The harking back to Greek and Roman models for today’s buildings should not, he believes, be countenanced. The machine education of the present generation is so readily obtained that it leads to mediocrity. It is no longer unusual to meet people who have a college degree. It is that very commonness of education that makes it mediocre. The man who is to be beyond the average must go very much further.

The first thing a student should learn, advises Mr. Bellows, is that all education that amounts to anything is self-education. Teachers, college, books these are only the opportunity for education. They are not education per se. Mr. Bellow’s own example is pertinent, and shows how well he practices what he preaches. As a college student, he cared nothing for the large train of compulsory subjects unless they appeared relevant to what he wanted to do. To him it mattered only that he learned what he wanted to learn. Some things were vitally interesting. Others had no apparent bearing on his work and were duly ignored. “I made some mistakes of judgment,” confessed Mr. Bellows. “I overlooked some important things that I now realize would have been valuable. But if they are important enough I learn them now, myself, and by that self-education I have a workable, usable thing.

“Forget the routine thing, forget the college degree,” he challenges. “The man of vitality is naturally self-educated. Education is largely personal. The young man with initiative will try to find a great man in his own field, will attach himself to him, will even pay to accept him as an apprentice, if possible, and will stick to him. But receiving education from a teacher has its obstacles. It pre-supposes that the teacher knows better than the taught, and the teacher therefore should himself do the great work, and be the great man, instead of attempting to instruct some one else how to do that which he cannot do himself.

“You do not know what you are able to do until you try,” went on Mr. Bellows, now exuberantly explaining his choicest methods. “In learning a topic, whether it be painting or architecture or any other art—and the practice of that art is constant learning—try everything that can be done. Try it in every possible way. Be deliberate. Be spontaneous. Be thoughtful and painstaking. Be abandoned and impulsive. Learn your own possibilities. Have confidence in your self-reliance! There is no impetus I have not followed, no method or technique I have not tried. There is nothing I do not want to know that has to do with life or art. Any artist, any architect, can mold his ideas on the same method. One is not a good architect unless he is an artist. Otherwise he is a mechanic. Therefore, since he is an artist, why can he not very properly practice this procedure?”

Visualizing an artist working out a picture “spontaneously,” we were caught by that word, and asked Mr. Bellows if spontaneity was not inconsistent with good art. He replied very forcefully that painting need not consciously conform to law. “Most so-called laws of the arts are dogmas. Rules and regulations,” he fervently declared “are made by sapheads for the use of other sapheads! Laws may be considered judicially. Certain laws are absolute, but many others are arbitrary. The absolute laws one is naturally in harmony with and will often subconsciously adhere to in spontaneous work even better than in deliberate effort, where there is not a profound basic knowledge. The arbitrary laws do not matter. They are human, fallible and disputable points of view. The academies and art schools are full of them.”

By this time we were sensing the wide sweep of Mr. Bellow’s thought over every possible phase and aspect of the painter’s art. If, to use the vernacular, he is disposed to try anything once in the hope of finding it valuable we thought we could help him by suggesting the Hambidge theory of Dynamic Symmetry. But along with the mass of pertinent information already stored in his mind was a full knowledge of and lively interest in Mr. Hambidge’s researches. “Some of the new things I have tried,” said Mr. Bellows, “have naturally taught me nothing. From some of them I have acquired knowledge that has been priceless. For example, many of my painter friends have scoffed at Hambidge’s law of dynamic symmetry as applied to composition. Now, I am not an authority on anything, but I must use what critical judgment I have up to my measure of understanding. Hambidge has shown me a great many things that are profoundly true, and I believe that any serious architect who will take the time to study this theory will be greatly helped.

“I see no contradictions in Mr. Hambidge’s contentions, nor have I ever heard one that holds water. Ever since I met Mr. Hambidge and studied with him I have painted very few pictures without at the same time working on his theory. I believe it to be as profound as the law of the lever or the law of gravitation. No man who practices the arts, and this seems to be particularly true of architecture, can, with justice to himself, ignore the research that Hambidge has made. It has never been disapproved, and the artist has but to learn and apply it in his work to know its helpfulness.

“It is the expression,” continued Mr. Bellows, warming to the subject, “of the basic working of the human mind. Geometry is the picture idea of the mechanism of thinking. Not only do I regard it as of vast importance and as expressing a fundamental natural truth, but even if it were not absolutely correct, it is anyhow useful to me.”

And it is just in this way that Mr. Bellows emphasizes the openness of mind with which he attacks every problem of his art. The fact that a thing is old and has stood the test of long practice will not interest this explorer into the unknown realms of art, as much as will some new idea to which he may bring all the resources of a fertile and well balanced mind. If there ever was an iconoclast in art it is George Bellows, but he does not destroy from the wanton motive of a doubter. When he departs from convention he can supply a reason for such departure that is so sane, so logical, that argument is silenced. When an architect will have attained, through an equally well-balanced mind, the same dauntless courage and independence, we shall hail him as the Moses who shall lead out of the Egypt of adaptation and precedent the whole of his profession.

At this point Mr. Bellows took from a large case a number of sketches and in the most convincing manner showed just how he had in every instance applied his knowledge of the Hambidge research. “Look,” said he, “how it simplifies this certain difficulty of arrangement, how it releases me from a heretofore distracting factor, and thereby permits me to concentrate all my efforts on the infinitely more difficult aspects.”

“If,” continued Mr. Bellows, standing in the middle of his studio, and speaking with the earnestness that characterizes the man even when least emphatic, “a thing is made easier by technical understanding, then by so much is it true that having this particular phase made easier, your strength is conserved for those things which yet remain troublesome.”

The logic of this is incontrovertible.

— George Bellows’ “The Relation of Painting to Architecture: An Interview with George Bellows, N. A., in Which Certain Characteristics of the Truly Original Artist Are Shown to Have a Vital Relation to the Architect and His Profession,” American Architect 118, December 29, 1920, pp. 847–851.

The Relation of Art to Everyday Things: An Interview with George Bellows, on How Art Affects the General Wayfarer

By Estelle H. RiesTHE curious thing about conventionality is that everybody criticizes it with many lamentations, and everybody sticks to it like a nail to a magnet. That is, almost everybody. When anyone happens to pull away out of the field of magnetic attraction—”or distraction”—the world stops talking of even the profiteer and begins to talk of the non-conformist instead. Mr. Bellows is one of the talked of, so we sought him out.

Many of us will recall that George Bellows is one of the younger men, he is only about thirty-eight, who as a painter has won almost every honor that can come to an artist. His portraits hang in the National Academy of Design. His splendid, virile war pictures won acclaim everywhere. His landscapes find frequent place in important galleries throughout the country. In all of them is portrayed the spirit of independence, of self-reliance, that dominates the man, and that has been at the bottom of his success. He was born in Columbus, Ohio, in 1882, and from the time he was five wanted little but to draw and paint. This he did, consistently and energetically, with the result just set forth.

If there ever was an iconoclast in art it, is George Bellows, but he does not destroy from the wanton motive of a doubter. When he departs from convention he can supply a reason for such departure that is so sane, so logical, that argument is silenced, and this we soon discovered when we talked with him.

Since we ourselves know little about art, we first asked Mr. Bellows what should be the proper attitude of the layman toward art.

“The layman,” he began, “needs first of all a change of heart. He should endeavor to experience a feeling of reverence in the presence of something he does not understand; to have a suspicion that a thing which looks ‘strange’ to him may have something to it that is really worth while. Any new and original work inevitably presents an element of strangeness, but that very element of strangeness may in itself prove fascinating if it will be thoughtfully considered. Instead of looking for the expected, why should one not find a far greater joy in the unexpected?’ Instead of going at a picture in a spirit of judgment, what a greater joy it is to experience the feeling of wonder! The joy of the child, you may call this. But is not the joy of the child greater, more joyous, more wise, even, than the cynicism of our pseudo-cultured adults?”

George Bellows has had the courage to break with the “accepted” tenets in art. Such an act has a broad application to people everywhere who desire to be distinctively original and to express their individuality without regard to all the man-made rules of precedent. What Mr. Bellows did in painting was not to discredit or minimize the worth of the great masters of the past, but, admitting their worth as enduring masterpieces, he determines to do something of his own. This we can all do in our daily work.

“I have no desire to destroy the past, as some are wrongly inclined to believe,” he explained. “I am deeply moved by the great work of former times, but I refuse to be limited by them! Convention is a very shallow thing. I am perfectly willing to override it if by so doing I am driving at a hidden truth.”

A painter, like folk in other fields, has a great wealth of previous work to draw upon. We asked Mr. Bellows why he had not drawn upon the work of men like Rembrandt and Titian.

“Oh, but I have drawn upon them. Strange as it may seem to you, I must testify that I have often painted as much like them, and other masters who have moved me, as I possibly could, but with this reservation: I have wished to understand the spirit and not the surface. Possibly your question arises from the fact that the idea is one somewhat generally held. There are, of course, many famous artists who are very naturally considered by the more or less thoughtless laymen as great masters, while they are in reality nothing of the sort. I am naturally influenced only by the artists of the past who, in my opinion, are significant great men. In these judgments I am often at variance not only with laymen but with a majority of our fellow artists. For instance, I don’t think that Bougereau amounted to much, and it might surprise some if I claim an influence from Botticelli.

“Every great master has put his heart and his own life on his canvas; he has fed on both art and life. It is easy to imitate, just as it is easier to enjoy inventions than to make them. If an artist has a sincere will to express his own life, he will not need to bother about his originality. If added to this he be possessed of rare personality, a man both witty and wise, a profound nature, in other words, he may well be called great. For myself I cannot know what of these I possess. I must take, develop and use what I have.”

Then he went ahead and did it, and his present works are the result. But let it be understood that this is not to be an exposition of Mr. Bellows’ work as a painter. It is that his work is representative of a splendid attitude toward art and life that matters, and by that attitude he is enabled to produce really original work. How he does it is of undeniable interest, and he has frankly given of himself in this interview to place before us every helpful experience.

Whether we practice an art, a profession, or a regular business, whether we are housekeepers, teachers, merchants, lawyers, craftsmen or anything else, it is our attitude toward our work that gets results. What George Bellows, by sheer grit and force of character, has done in painting, we can, by similar grit and force, do in our own work.

“It is resolution and determination and high intelligence that make for achievement,” he declared. “The theory of standardization is one thing. It is efficient. But it is not beautiful. To standardize our methods is to court drudgery and monotony. It is to follow the wiles of tradition whether they are reasonable or not. It is to be conventional for the sake of convention, and to kill individuality and invention for the want of initiative. Standardize, yes, our purely physical processes, the unimportant details of our daily work. But anything that is worth doing is entitled to thoughtful consideration, and to standardize it is to rob it of that variety and spirit that make it worthwhile. Or if standardizing is inevitable, let us put it on the high plane of our personal endeavor and not accept the present standards as adequate.

“If we must standardize let us improve the standards. Let us improve them to their very highest development and then perhaps we may justly standardize.” What, then, does Mr. Bellows himself do to exemplify this ideal? What is the secret of his success? With his trenchant comments on art and its wide range interspersed, consider Mr. Bellows’ own words. “There is no new thing proposed, relating to my art as a painter, that I will not consider,” Mr. Bellows announced. “The fact that a thing is old and has stood the test of time has always been too much a god. What should interest us is exploration, not adaptation. Take, for example, our interior decorators, our architects, our furniture makers and many of our better craftsmen. They adhere strictly to period style, to ancient and well-worn doctrines.

“Now as for me,” he went on, “I do not believe in period style. It seems second-hand. All living art is of its own time. Period style is a reversion to past types. Period styles of the present day would be desirable and would vary with their locality. There would need to be no monotony. These styles, if they were devised, could be as glowing, as virile, as truly fine as any that we now worship, for they would be of our own time. We would understand them. We could do them better. They would have greater significance for the layman, for they would not be shrouded in mystery and obscure allusion.”

“Then,” we prompted, “what would you suggest to attain more general initiative?”

“The fault lies with our methods of education,” replied Mr. Bellows. “Take your schools of architecture, for instance. They teach conventional architecture, period architecture. I do not believe in education as an end, so much as in the opportunity for men of imagination to have opportunity. But your schools interfere with such an opportunity. If an architect tried to create something independent of ‘periods’ he would have a hard time to place his work. And yet all the possibilities of significant form have not been exhausted, have they?” We had to admit they have not. “Why, then, should architects, or any craftsmen, worship the ‘period’ as they do?” questioned Mr. Bellows. “If there are further significant forms to be originated, and philosophy agrees that there are, I can see no reason why we are bound to the existing forms and scorn any attempt to create the new.”

The harking back to Greek and Roman models for today’s buildings should not, he believes, be countenanced. “I am sick of American buildings like Greek temples, and of rich men building Italian homes. It is tiresome and shows a lack of invention. Greek temples with glass windows are foolish.”