Teach close reading skills, portraiture, and implicit stereotypes with George Catlin’s Indian Gallery. Share the Look and Learn interactive module with your students.

George Catlin’s Indian Gallery is in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s collection. See their website to learn more about George Catlin and his Indian Gallery. Access the embedded links below for high-quality images that can be magnified and for additional information on each painting.

I have, for many years past, contemplated the noble races of red men, who are now spread over these trackless forests and boundless prairies, melting away at the approach of civilization. Their rights invaded, their morals corrupted, their lands wrested from them, their customs changed, and therefore lost to the world; and they at last sunk into the earth, and the ploughshare turning the sod over their graves, and I have flown to their rescue—not of their lives or of their race (for they are “doomed” and must perish), but to the rescue of their looks and their modes, at which the acquisitive world may hurl their poison and every besom of destruction, and trample them down and crush them to death; yet, phoenix-like, they may rise from the “stain on a painter’s palette,” and live again upon canvas, and stand forth for centuries yet to come, the living monuments of a noble race. For this purpose, I have designed to visit every tribe of Indians on the Continent, if my life should be spared; for the purpose of procuring portraits of distinguished Indians, of both sexes in each tribe, painted in their native costume; accompanied with pictures of their villages, domestic habits, games, mysteries, religious ceremonies, etc., with anecdotes, traditions, and history of their respective nations.

— George Catlin, in his North American Indians: Being letters and notes on their manners, customs, and conditions, written during eight years’ travel amongst the wildest tribes of Indians in North America, 1832–1839, page 17.

I wish to inform the visitors to my Gallery that, having some years since become fully convinced of the rapid decline and certain extinction of the numerous tribes of the North American Indians; and seeing also the vast importance and value which full pictorial history of these interesting but dying people might be to the future ages—I set out alone, unaided and unadvised, resolved, (if my life should be spared), by the aid of my brush and my pen, to rescue from oblivion so much of their primitive looks and customs as the industry and ardent enthusiasm of one lifetime could accomplish, and set up in a Gallery unique and imperishable, for the use and benefit of future ages.

— George Catlin, from his exhibition catalogue in the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, 1840

History textbooks oftentimes use a George Catlin painting when they present the Westward Expansion, so students may recognize some of these paintings. Catlin however did not exhibit his painting one at a time. He hung them in elaborate grids, salon-style. Tell students this is a small representative sampling of the original gallery that had over 500 paintings. Click on an image to enlarge the gallery and scroll through the paintings with the key pad’s directional arrows. Match the number on each frame to the list below and tell students the title of each painting or share this pdf of of Catlin’s original exhibition catalog and ask volunteers to read aloud Catlin’s title and description. Then, ask what is going on in this gallery of paintings? Encourage students to discuss the gallery as a whole and to identify individual images that are especially meaningful to them. Also, encourage students to identify the evidence that supports the reasoning behind their interpretations. Students should likewise share wonderings and voice confusions. As the conversation slows, explain you are going to read two Catlin quotes that describe his thoughts and motivations in creating this gallery. After reading the quotes ask how does this new insight change your understanding of the paintings? Catlin’s word choice and phrasing is pretty loaded. Is he serving or exploiting the Native Americans he paints? This question will be explored throughout this unit so record the reasoning on either side but don’t be too quick to answer it.

Indian Portraits (Catlin’s catalog lists 310 “Indian Portraits”—bust, half-length, and full length—from 48 tribes—61% of the gallery.)

- #2 Múk-a-tah-mish-o-káh-kaik, the Black Hawk, Prominent Sac Chief; in his war dress and paint. Strings of wampum in his ears and on his neck, and his medicine bag (the skin of the black hawk) on his arm. This is the man famed as the conductor of the Black Hawk War. Painted at the close of the war, while he was a prisoner at Jefferson Barracks, in 1832. (Sacs, 1832)

- #3 Náh-se-ús-kuk, Whirling Thunder, Eldest Son of Black Hawk. A very handsome man. He greatly distinguished himself in the Black Hawk War. (Sacs, 1832)

- #7 Wah-pe-kée-suck, White Cloud (called the Prophet), One of Black Hawk’s principal warriors and advisers. Was a prisoner of war with Black Hawk, and travelled with him through the Eastern states and cities, in chains. (Sacs, 1832)

- #15 Pash-ee-pa-hó, the Little Stabbing Chief (the Younger), One of Black Hawk’s Braves, (Sacs, 1832)

- #117 Wah-ro-née-sah, the Surrounder. Chief of the Tribe, quite an old man; his shirt made of skin of a grizzly bear, with the claws on. (Otetoes, 1832)

- #124 Kah-béck-a, the Twin, wife of Bloody Hand, (Riccarees, 1832)

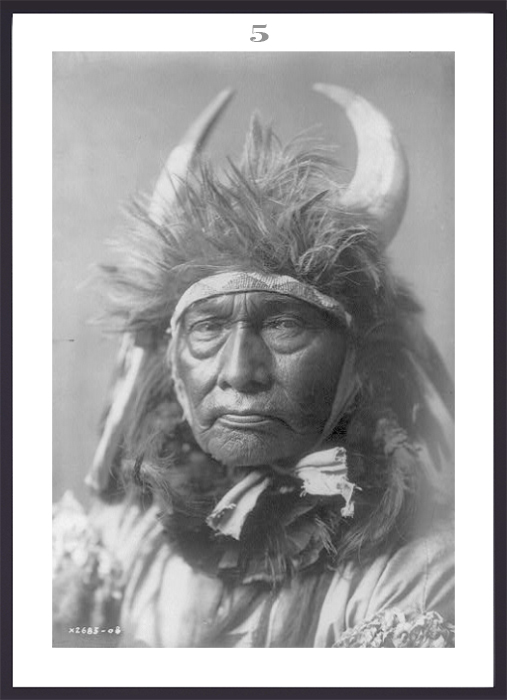

- #128 Máh-to-tóh-pa, the Four Bears, second Chief, but the favorite and popular man of the nation; costume splendid, head-dress of war eagles’ quills and ermine, extending quite to the ground, surmounted by the horns of the buffalo and skin of the magpie. (Mandans 1832)

- #129 Mah-tó-he-ha, the Old Bear; a very distinguished Brave; but here represented in the character of a Medicine Man or Doctor with his medicine or mystery pipes in his hands, and foxes’ tails tied to his heels, prepared to make his last visit to his patient, to cure him, if possible, by hocus pocus and magic. (Mandans, 1832)

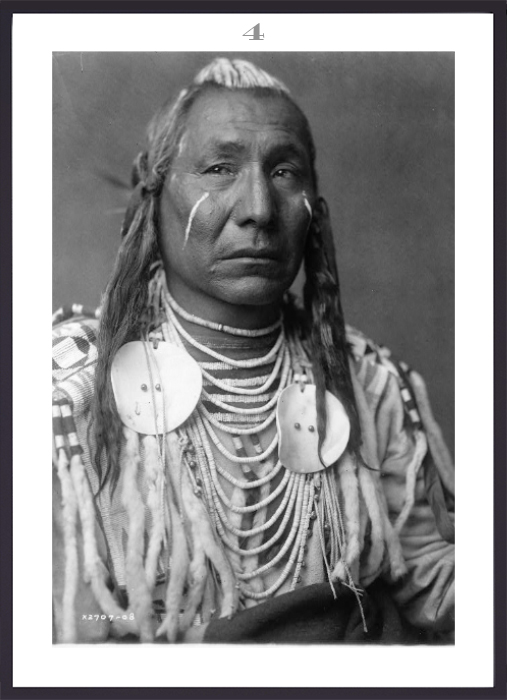

- #149 Stu-mick-o-súcks, the Buffalo’s Back Fat. Head Chief of the Tribe, in a splendid costume, richly garnished with porcupine quills, and fringed with scalp-locks. (Blackfeet, 1832)

- #150 Eeh-nís-kim, the Crystal Stone; wife of the Chief (No. 149). (Blackfeet, 1832)

- #159 Tcha-aés-ka-ding, boy, four years old, wearing his robe made of the skin of a racoon: this boy is the grandson of the chief (No. 149) and is expected to be his successor. (Blackfeet, 1832)

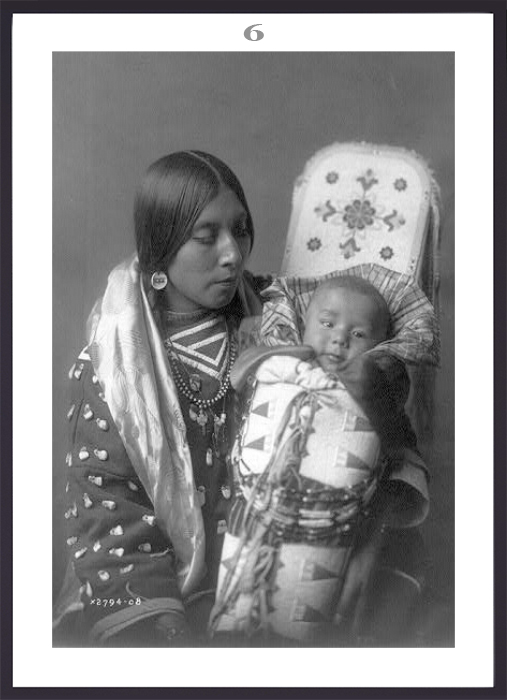

- #177 Tsee-moúnt, Great Wonder, Carrying Her Baby in Her Robe. (Cree, 1832)

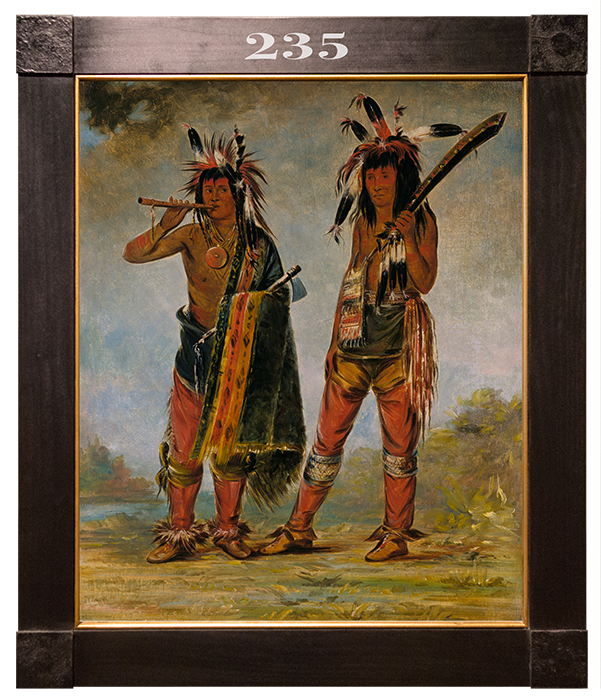

- #235 Two in a group, names not known; one with his war club and the other with his lute at his mouth. (Menomonies, 1835)

- #299 Tul-lock-chísh-ko, He who Drinks the Juice of the Stone. Full length, in dress and attitude of a ball player. With ball-sticks in his hand, and tail, made of white horse hair, attached to his belt. (Choctaw, 1834)

- #304 Co-ee-há-jo, ———; a Chief very conspicuous in the present war. (Seminole —Runaway, 1838)

Landscapes (Catlin’s catalog lists 92 “Landscapes”—18% of the gallery.)

- #374 View on Upper Missouri—Prairie Meadows burning, and a party of Indians running from it in grass eight to ten feet high. These scenes are terrific and hazardous in the extreme, when the wind is blowing a gale. (1832)

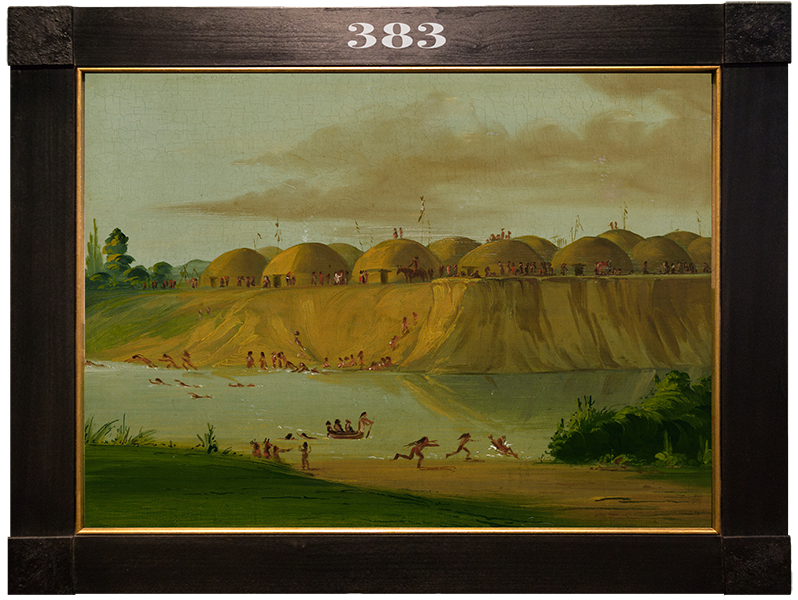

- #383 View on the Upper Missouri—Minatarree (Hidatsa) Village, earth-covered lodges—on Knife River, 1810 miles above St. Louis. Batiste, Bogard, and myself ferried across the river by an Indian woman, in a skin canoe, and Indians bathing in the stream. (1832)

Sporting Scenes (Catlin’s catalog lists 22 “Sporting Scenes”—4% of the gallery.) Note: Catlin’s “Sporting Scenes” are exclusively hunting based. He included athletic events in “Amusements and Customs.”

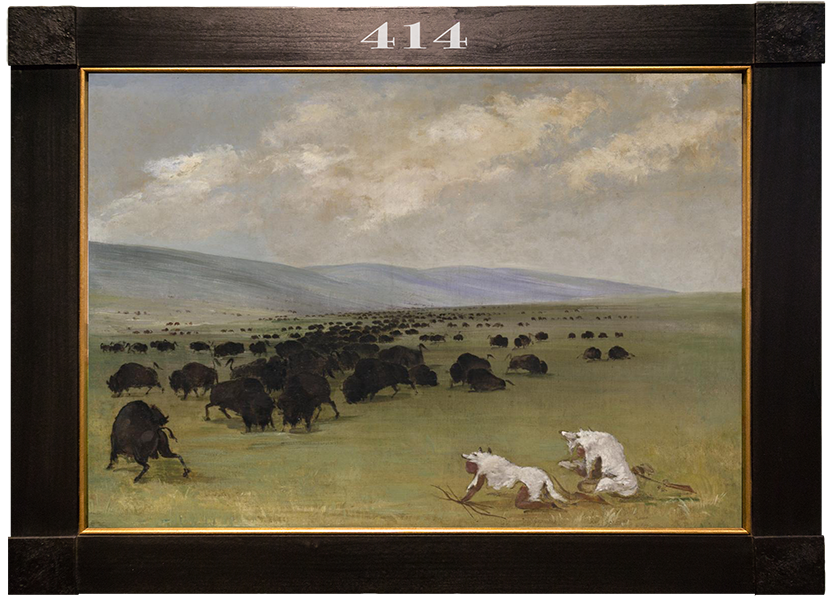

- #414 Buffalo hunt under the wolf-skin mask (1846–1848)

- #415 Buffalo Chase, Mouth of the Yellowstone; animals dying on the ground passed over; and my man Batiste swamped in crossing a creek. (1832–1833)

Amusements and Customs (Catlin’s catalog lists 80 “Amusements and Customs”—16% of the gallery.)

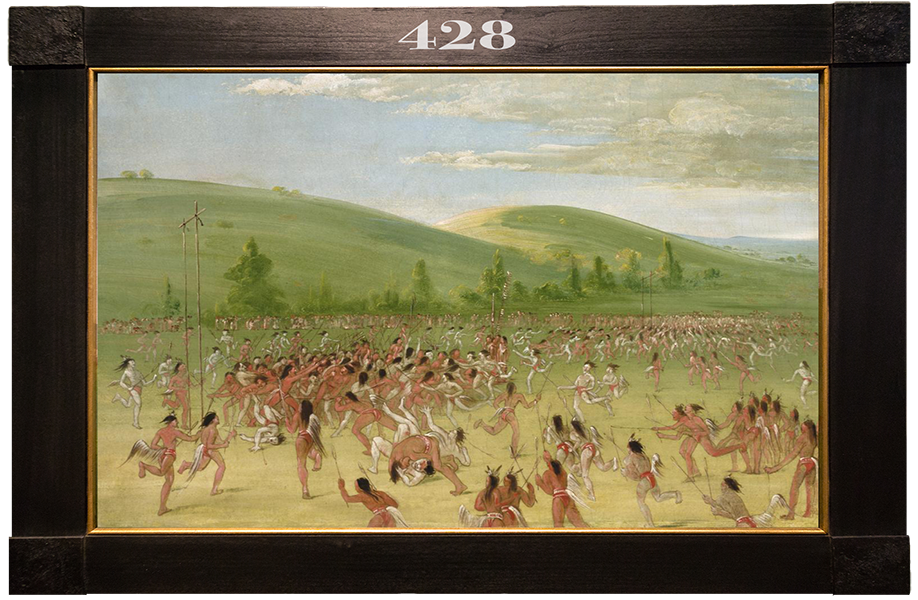

- #428 Ball-play of the Choctaw—ball up—one party painted white; each has two sticks with a web at their ends, in which they catch the ball and throw it —they all have tails of horse hair or quills attached to their girdles or belts. Each party has a limit or bye, beyond which it is their object to force the ball, which, if done, counts them one for game. (1834–1835)

- #434 Canoe Race—Chippeways in Bark Canoes, near Sault de St. Mary’s; an Indian Regatta, a thrilling scene. (1836-1837)

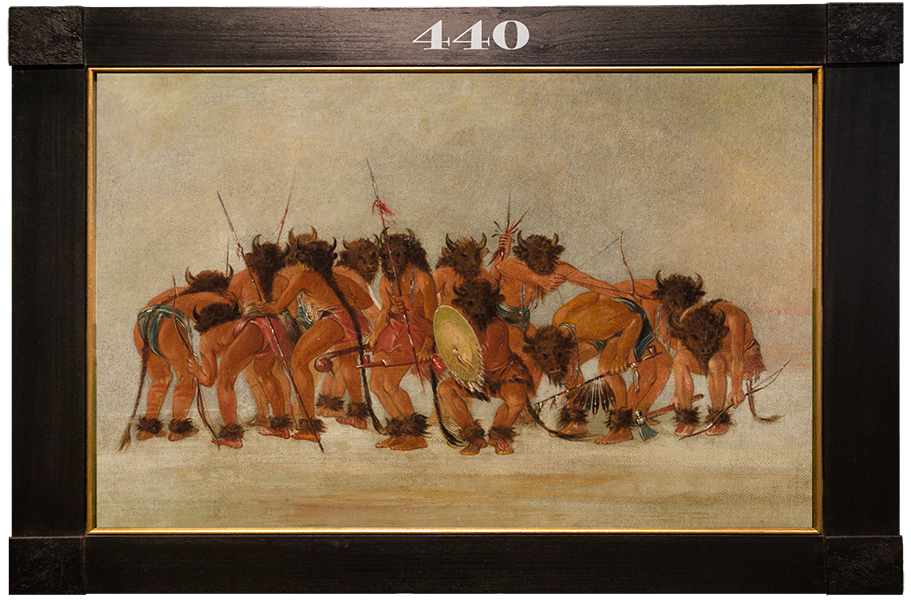

- #440 Buffalo Dance, Mandans, with the Mask of the Buffalo on. Danced to make the buffalo com, when they are like to starve for want of food. Song to the Great Spirit, imploring him to send them buffalo, and they will cook the best of it for him. (1835–1837)

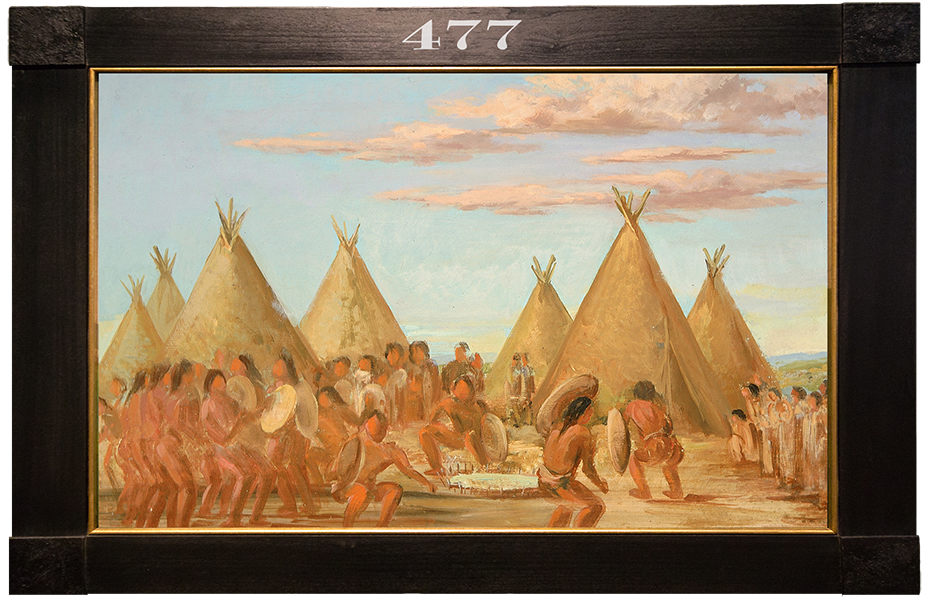

- #477 Smoking the Shield. A young warrior, making his shield, invites his friends to a carouse and a feast, who dance around his shield as it is smoking and hardening over a fire built in the ground. (1837–1839)

- #487 Feats of Horsemanship. Camanchees throwing themselves on the side of their horses, while at full speed, to evade their enemies’ arrows—a most wonderful feat. (1834-1835)

- #491 Crow Lodge, of twenty-five Buffalo Skins, beautifully ornamented. This splendid lodge, with all of its poles and furniture, was brought from the foot of the Rocky Mountains. (1832–1833)

Begin with art history

At the age of 23 George Catlin was growing restless. Like his father and older brother he had become a small-town lawyer. But his life lacked the sense of adventure he enjoyed when he was hunting and fishing in the forests near his boyhood home in Wilkes Barrie, Pennsylvania. He found relief from the humdrum by dabbling in painting. Early on Catlin established himself as a self-taught miniature painter, a popular artform that rendered intimate portraits that were fitted into jewelry or snuff box covers. As his skill grew so did his ambition and the scale of his work. In time he gave up his law practice, dedicating himself to becoming an artist. Like many artists from the time, he tried to tap into the more lucrative business of portrait painting. While he found some favor with powerful politicians such as DeWitt Clinton, the governor of New York who had just spearheaded the building of the Erie Canal, his work lacked expected artistic refinements. As one influential critic ruthlessly derided his full-length portrait of Clinton, “…Catlin was utterly incompetent. He has the distinguished notoriety of having produced the worst full-length which the city of New York possesses.”

As professional struggles began to weigh on Catlin, a chance encounter with a group of Plains Indians touring major East Coast cities on their way to negotiate in Washington D.C. caught his imagination and set the course for his life.

I closely applied my hand to the labours of the art for several years; during which time my mind was continually reaching for some branch or enterprise of the art, on which to devote a whole lifetime of enthusiasm; when a delegation of some ten or fifteen noble and dignified-looking Indians, from the wilds of the “Far West,” suddenly arrived in the city.…In silent and stoic dignity, these lords of the forest strutted about the city for a few days, wrapped in their pictured robes, with their brows plumed with the quills of the war-eagle, attracting the gaze and admiration of all who beheld them. After this they took their leave for Washington City, and I was left to reflect and regret, which I did long and deeply, until I came to the following deductions and conclusions.…The history and customs of such a people, preserved by pictorial illustrations, are themes worthy the lifetime of one man, and nothing short of the loss of my life, shall prevent me from visiting their country, and of becoming their historian.

The dream grew with the realization that this unconventional path circumvented the barbs and competition of the established art world and leveraged his skills as an outdoorsman. Ignoring the protests of his family and without any financial backing, the headstrong Catlin set off in the Spring of 1830 just as President Andrew Jackson’s harsh Indian Removal Act was signed into law. Upon landing in St. Louis, the gateway to the West, Catlin introduced himself to the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Western Tribes, General William Clark, the renowned explorer of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Taken with Catlin’s passion and cause, Clark shared his maps and used his influence to help Catlin gain access to numerous midwestern tribes.

In the course of the next six years, Catlin made five trips into the frontier eventually visiting 48 tribes. An early set of Indian portraits was of Black Hawk and a small group of followers imprisoned at Jefferson Barracks. In 1832 he made a historic and highly productive trip up the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers to the Fort Union Trading Post in North Dakota, where leaders from numerous tribes convened for a council meeting. After executing 135 paintings in just three months, the driven Catlin ventured south to a Mandan village where he witnessed and documented a tortuous four-day initiation ceremony for male warriors. When a smallpox epidemic wiped out this tribe six years later, Catlin’s paintings were recognized as a noted ethnographic achievements. In 1834 Catlin joined a U.S. military expedition to the Southwest where he encountered the Comanche at the height of their nation when they were celebrated as the “Lords of the Plains.” Fever plagued the expedition and almost killed Catlin, as it did more than 100 others. By 1836 Catlin had amassed a gallery of 500+ paintings and a museum’s worth of artifacts which he shipped back to New York for exhibition.

To complete his life’s mission Catlin had to be as ardent in bringing his Indian Gallery to the general public as he was in creating the paintings. His initial exhibitions in New York City were met with great success, but over time the crowds dwindled and he was compelled to tote his expansive gallery to major cities throughout the Northeast. Catlin hoped to sell the collection intact to the U.S government. But, Catlin’s criticism of the government’s inhumane Indian policies and the way fur traders used whiskey to ply their trade made powerful enemies who stymied his efforts. In the hopes of shaming the Congress to action, Catlin threatened to take his American treasure to Europe. When no financial offer was extended Catlin packed up his Indian Gallery—eight tons of freight and two live grizzly bears —and set sail for England in 1839. Upon landing, he rented space in London’s Egyptian Hall where his exhibition was acclaimed and he achieved minor celebrity status. He became the toast of high society as the aristocracy flocked to his exhibit including Queen Victoria of Great Britain and King Louis Philippe of France. Over the course of the next decade he toured with his Indian Gallery throughout Europe, even showing in the Louvre.

During these years, the mounting costs of promotion, site rentals, and transportation caused Catlin to shift from being an advocate to being an entertainer, from being an artist to being a showman. Early on his exhibits were scholarly affairs as Catlin, dressed in buckskins, lectured an educated audience about Indian ways in a gallery full of artifacts and paintings hanging floor to ceiling in an elaborate grid. He soon realized, however, that to recoup his investments he would need to broaden his market appeal with more theatrical presentations. The artifacts became costumes as he created tableaux vivants, living installations representing key events in his talks. These static tableaux eventually assumed dynamic motion as out-of-work Londoners with thick cockney accents were hired to reenact Sioux chants, rituals, and war cries. The cumbersome paintings were put in storage when Catlin toured the provinces with his ersatz Indians and only the most dramatic artifacts—clubs, spears, tomahawks, and scalping knives polished to a high sheen. Even though Catlin added greater authenticity to his show by hiring real Ojibwas and Iowa Indians who happened to be touring Europe, a series of unfortunate relationships and events completed his financial demise. In 1852, the railroad tycoon Joseph Harrison saved Catlin from debtors prison and the disbursement of his Indian Gallery, when he paid off Catlin’s creditors and took the entire collection as collateral. For the remainder of his life Catlin tried to recreate his Indian Gallery through drawings from memory and dubious wilderness expeditions, but he never saw these paintings again. In 1879, seven years after Catlin’s death, Joseph Harrison’s widow, Sarah, saved the collection from the dank, rodent-infested basement of a boiler factory when she donated 422 of the original 507 paintings to the Smithsonian Institution.

Catlin was as controversial in death as he was in life. Some see Catlin as a passionate, uncompromising advocate for Native Americans who used the power of art to celebrate their nobility and highlight all that was being lost as settlers encroached upon their cultures? Others see him as a self-promoting cultural colonist who appropriated and distorted Native American images, artifacts, and stories to enhance his own prestige and wealth. His exploits and extensive writings offer ample evidence to support both views. Catlin was a man of his times with all of its shortcomings and misunderstandings. And while we can’t separate Catlin from his time period, his life’s work, both its good intentions and failings, offer lessons for contemporary portrait artists and ethnographers as they consider fair and equitable ways to collaborate with and compensate subjects from other cultures.

Look like an art critic

George Catlin’s Indian Gallery is in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s collection. See their website to learn more about George Catlin and his Indian Gallery. Access the embedded links above for high-quality images that can be magnified. Thank you Smithsonian American Art Museum!

Catlin’s salon-style exhibitions

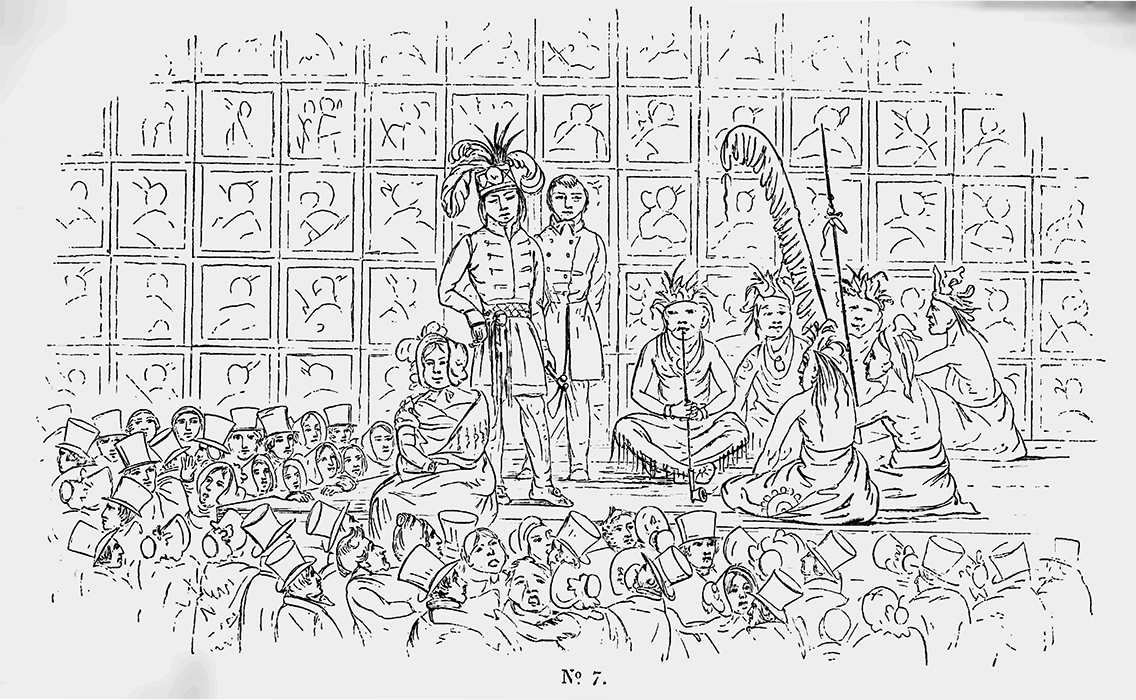

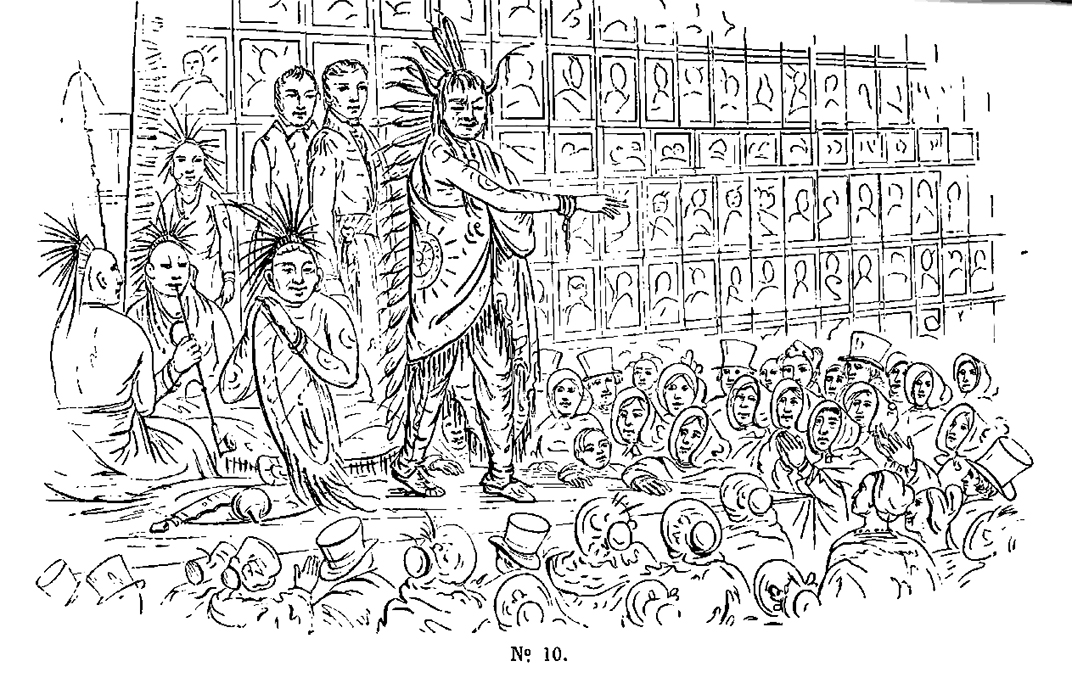

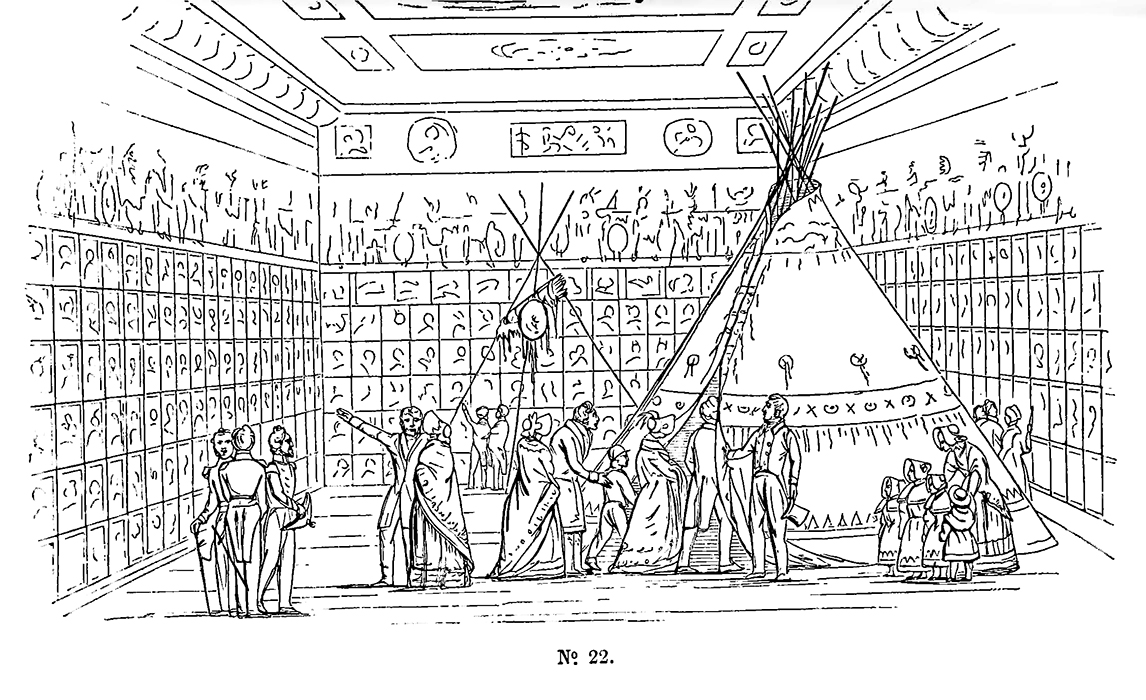

Point out and discuss: (Click on a gallery image to enlarge.) The 500+ paintings in Catlin’s Indian Gallery were hung in an elaborate grid formation, salon-style. These three illustrations from Catlin’s Notes of eight years’ travels and residence in Europe with his North American Indian collection show how his exhibits were displayed. Illustration No. 7 shows Catlin’s exhibit at the Egyptian Hall where the paintings hang from floor-to-ceiling and surround a raised platform on which the Indians performed and Catlin lectured. Illustration No. 10 shows another view of Egyptian Hall with the Ojibway Indians on stage. Illustration No. 22 shows the Indian Gallery in the Louvre with its centerpiece wigwam made from 20 buffalo skins. Catlin is talking with King Louis Philippe of France as his children arrive on the right.  See a recent exhibit at the Smithsonian American Art Museum that honors this salon-style hanging. How did Catlin’s expansive, all-encompassing exhibition serve his intentions?

See a recent exhibit at the Smithsonian American Art Museum that honors this salon-style hanging. How did Catlin’s expansive, all-encompassing exhibition serve his intentions?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: The expansiveness of the Indian Gallery gives an immediate sense of a robust, thriving population with varied cultures. The distinct looks—hair styles, clothing, jewelry, and other artifacts—evoke diverse ways of life. The portraits make you see individuals, at the same time, by grouping them together, you recognize their communalism and familial networks. Like traditional portraiture, these portraits show a respect for the individual, emphasizing their nobility, beauty, wealth, power, and importance. By including their Indian names and a brief description of their achievements and status in the tribe, Catlin reveres them as individuals and as community members. By asking them to sit for a portrait and waiting on them to prepare and dress in their finest, Catlin collaborates with his subjects in a respectful manner. The portraits look directly into the eyes of the viewer. This gaze establishes an intimacy and a relationship with the subject. The gaze can also be incriminating, questioning the viewer’s complicity. You see their humanity. The full-length portraits express the subject’s physicality. You see their strength, their bearing, and for some, even their athletic prowess. You can see the intricacies and coordination of their wardrobe. The landscapes and paintings of group activities, such as buffalo hunting and athletic events, highlight teamwork and the managing of natural resources. Hanging the paintings in tight columns and rows highlight and celebrate relationships and offer a multidimensional view of diverse cultures.)

Exploring bias

Point out and discuss: All artists express a worldview that reflects their own unique perspective. Because Catlin’s mission was to visit “every tribe of Indians on the Continent” and “become their historian,” his Indian Gallery was part art, part ethnography. This makes his perspective and any related bias more pertinent. Does Catlin’s Indian Gallery provide a fair and balanced overview of Native American cultures? Or, does it reflect a bias? Who or what subjects does Catlin emphasize? Who or what subjects are lost in his blindspots?

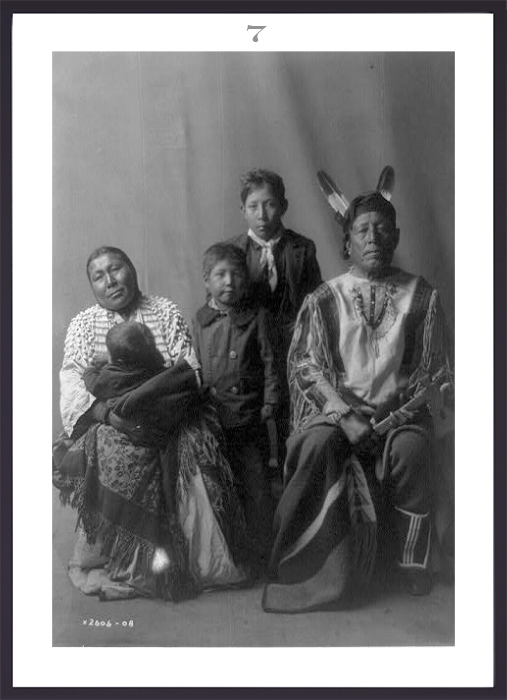

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: Catlin’s Indian Gallery favors male subjects, especially powerful leaders and warriors. He celebrates the physical prowess of male hunters and athletes. Women, children, and common folk are in part, or completely, ignored. When women and children are recognized, they are referenced in relation to their male counterparts.)

Follow-up: Bias can be intentional, but it can also result from unintended consequences. Recognizing an artist’s biases and blindspots can awaken a viewer to nuances in the art. Building on Catlin’s history above and students’ personal insights consider these questions. How might Catlin’s upbringing, interests, and worldview have influenced how he chose his subjects? How might Catlin’s subjects self-selected? Consider how Catlin may have inadvertently narrowed his pool of subjects by how and where he introduced himself to various Native American groups. Consider how others saw him and how that may have impacted who was open to his entreaties and who avoided him?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: Catlin had a special affinity for fishing and hunting. That may explain why he was especially taken with buffalo hunting. Because men were typically the hunters (as opposed to the gatherers) in a tribe that may have narrowed his focus on their efforts. Because Catlin came from a patrilineal society, and because the men in his world had more power and rights than women, he may have thought the social hierarchy was the same for the natives he met and he pursued these expected lines of influence. Maybe, because he was a man, he identified with men easier. The opposite may also be true. Because he was a man, traveling in a contingent of other men, the men in the tribe identified with him easier. When he sought subjects in garrisons as prisoners of war or at council meetings at trading posts he entered environments where men traditionally held sway. Likewise, when he traveled with a military escort, he was perceived as being part of a warrior class—positions typically relegated to men. To expedite his efforts and gain trust quickly, Catlin intentionally solicited support from influential leaders. As the descriptions in the Indian Gallery catalog attest, Catlin was captivated by exotic artifacts, fashions, and embellishments. It stands to reason that the most privileged in a community would have these in greater abundance and higher quality, thus attracting his attention. If Catlin had travelled with women, visited Native American homes for an extended period of time, built collaborative relationships, and focused on the inner workings of tribal life his Indian Gallery would likely look substantially different and would likely have included more women and children.)

Comparing media and identifying implicit stereotypes

70 years after Catlin ventured into the North American frontier to chronicle Native American cultures, another artist pursued a similar undertaking. In 1906 the photographer and ethnographer Edward Curtis echoed Catlin’s mission to establish a visual record of a “doomed” people as he set off to record Native American cultures.

The great changes in practically every phase of the Indian’s life that have taken place, especially within recent years, have been such that had the time for collecting much of the material, both descriptive and illustrative, herein recorded, been delayed, it would have been lost forever. The passing of every old man or woman means the passing of some tradition, some knowledge of sacred rites possessed by no other; consequently the information that is to be gathered, for the benefit of future generations, respecting the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind, must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost for all time. It is this need that has inspired the present task.

— Edward S. Curtis in the General Introduction of his series The North American Indian

Curtis shared his research and photographs with the world through his The North American Indian, a twenty-volume publication totaling nearly 5000 pages of narrative text and over 2200 images. 1074 of these and related photographs can be found in the Library of Congress’ Curtis collection.

As was done with the excerpted Indian Gallery above, click on an image to enlarge the gallery and scroll through the paintings with the key pad’s directional arrows. Match the number on each frame to the list below and tell students the title of each painting.

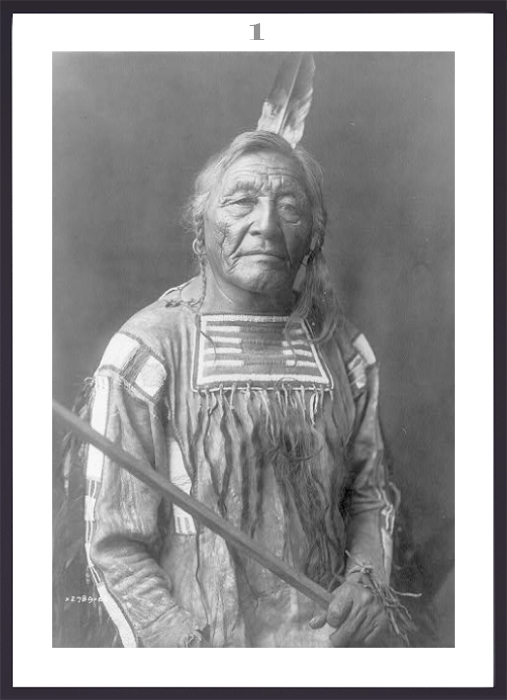

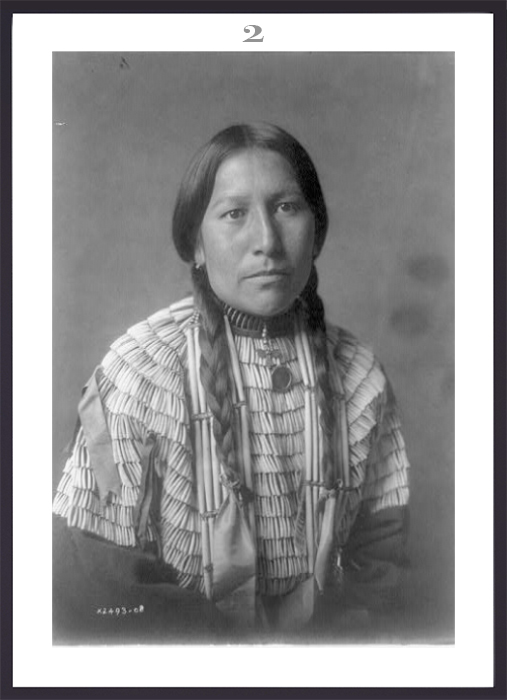

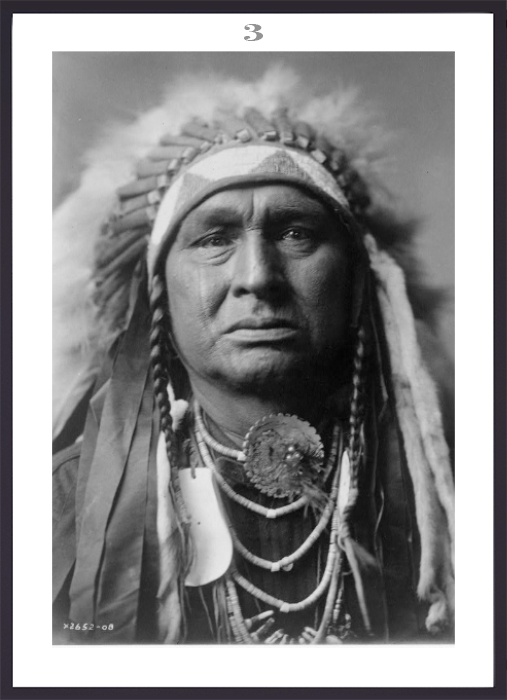

- Sitting Elk—Apsaroke half-length portrait, facing front, holding staff his right hand.

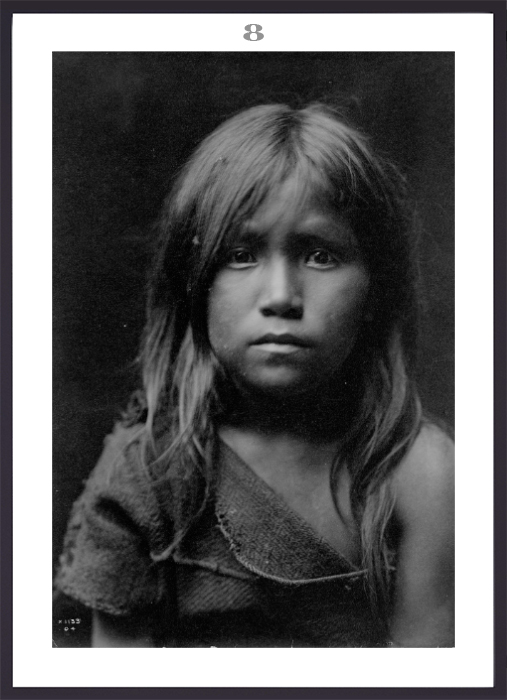

- Daughter of American Horse Half-length portrait, facing right.

- White Man Runs Him, Apsaroke

- Red Wing—Apsaroke

- Bull Chief—Apsaroke

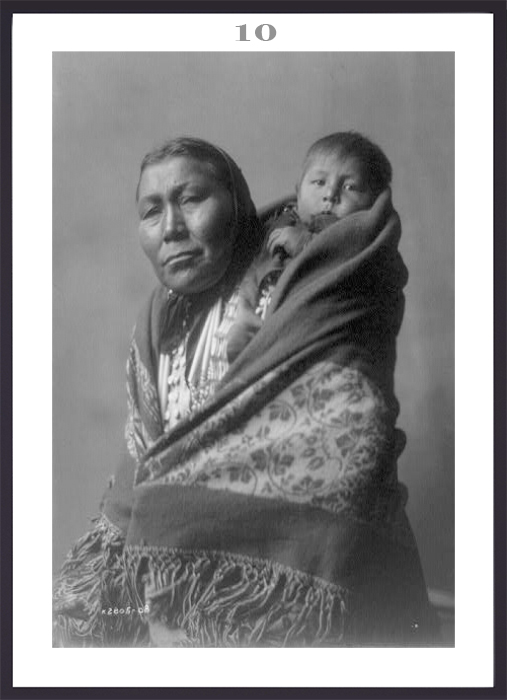

- Mother and child—Apsaroke Portrait of a woman, half-length, seated, facing right, holding baby in beaded cradleboard.

- Good Bear Hidatsa Indian posed, full-length, seated, facing front, with his wife and three children.

- Hopi Angel Photo shows a Hopi girl, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing front.

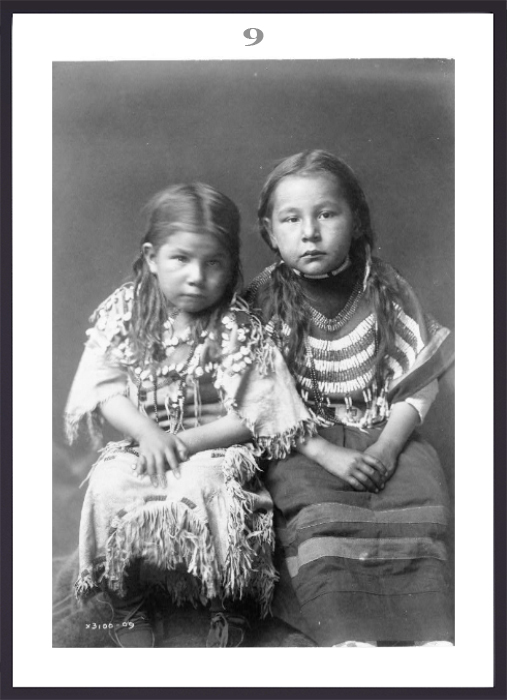

- Bull Shoe’s children

- Hidatsa mother

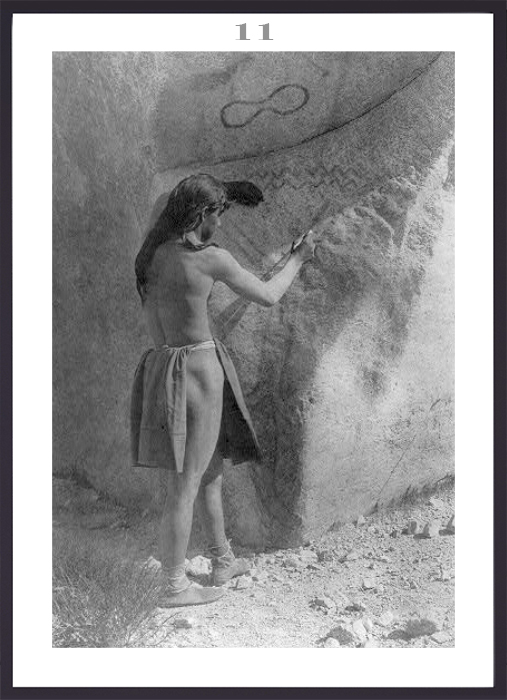

- The primitive artists—Paviotso Paviotso man standing, marking side of glacial boulder that already has petroglyphs on it.

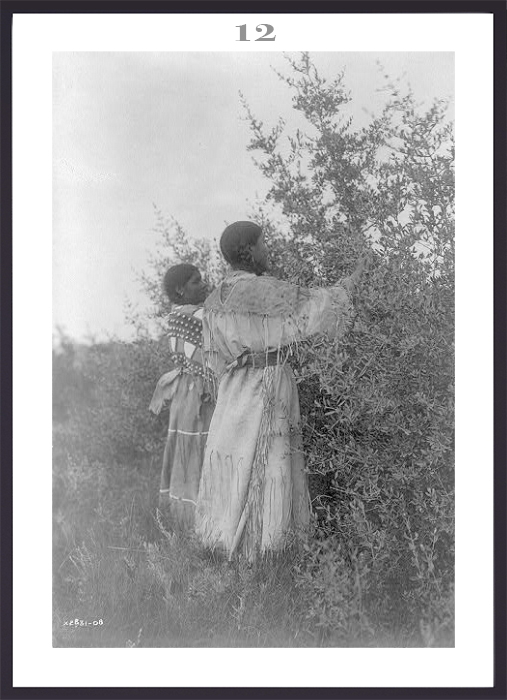

- Buffalo berry gatherers—Mandan

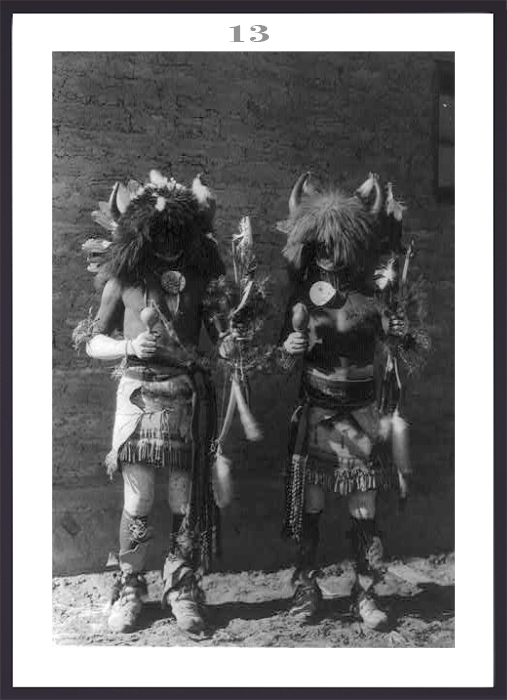

- Tesuque buffalo dancers Two Native American men in costumes wearing horns of buffaloes

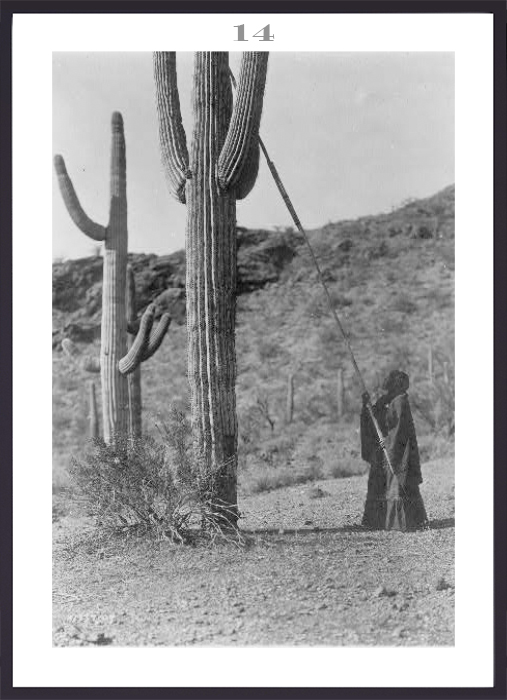

- Gathering hasen—Qahatika Woman using long pole to harvest cactus fruit, Arizona.

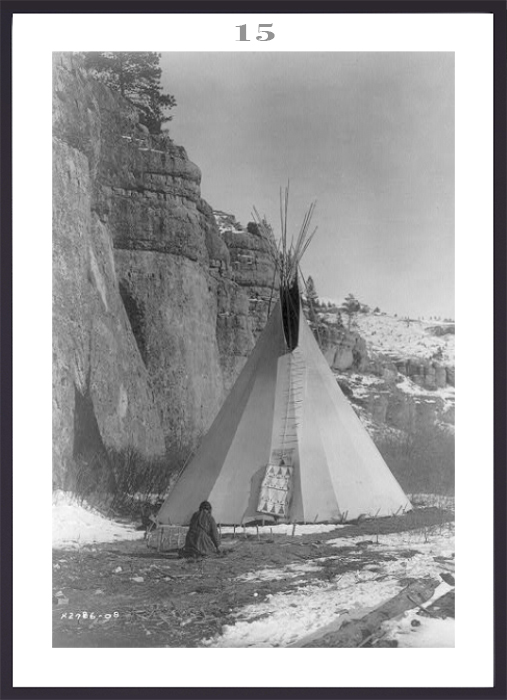

- Hide stretching—Apsaroke Apsaroke woman stretching hide that has been secured to the ground by stakes, tipi in background, cliff on left.

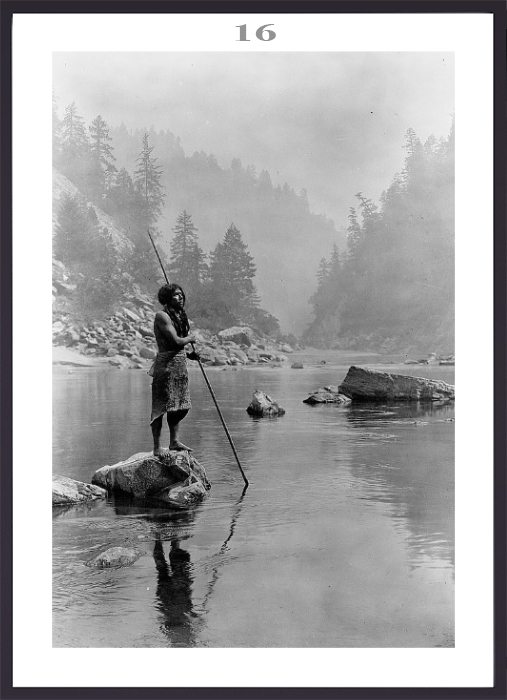

- A smoky day at the Sugar Bowl—Hupa Hupa man with spear, standing on rock midstream, in background, fog partially obscures trees on mountainsides.

- A heavy load

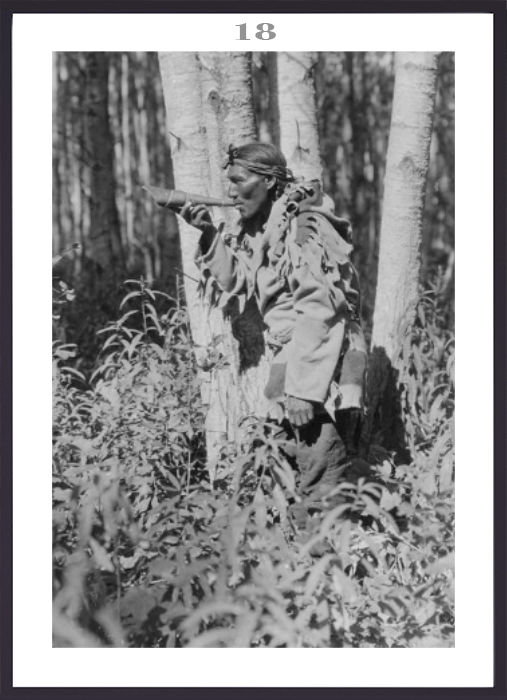

- Calling a moose—Cree

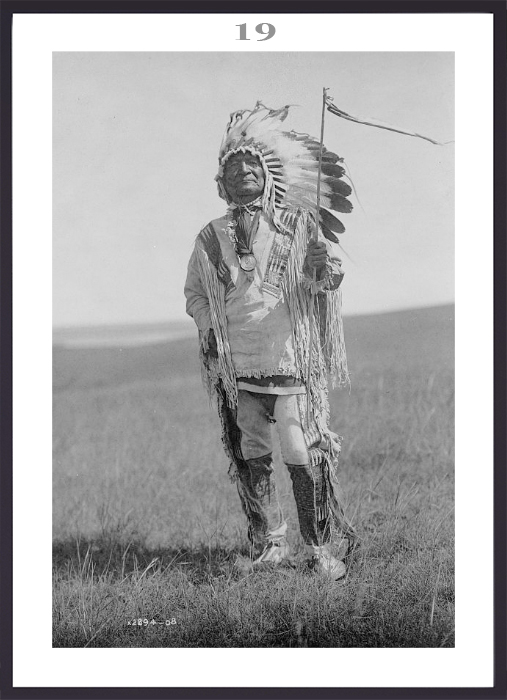

- Arikara chief

- The eagle catcher Photo shows a Hidatsa Indian standing on large rock overlooking a valley, full-length, left profile, holding an eagle.

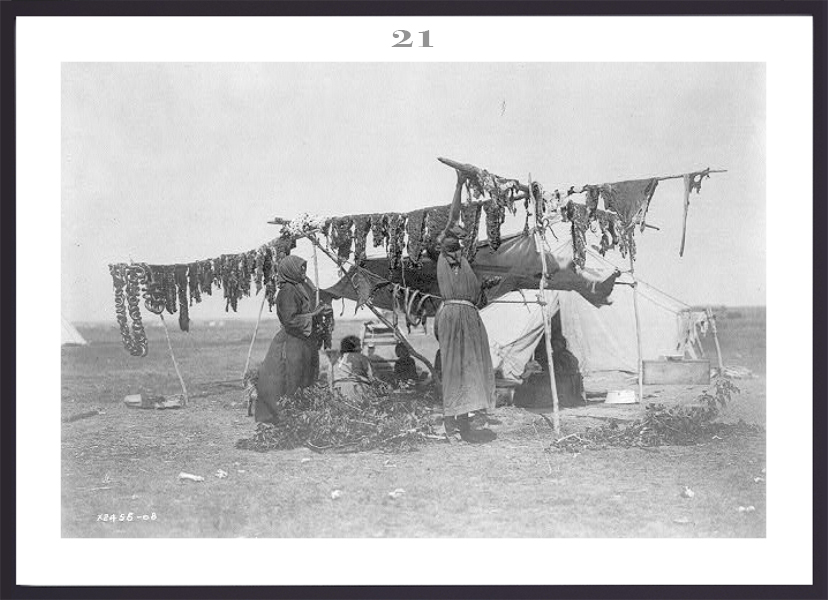

- Drying meat Two Dakota women hanging meat to dry on poles, tent in background.

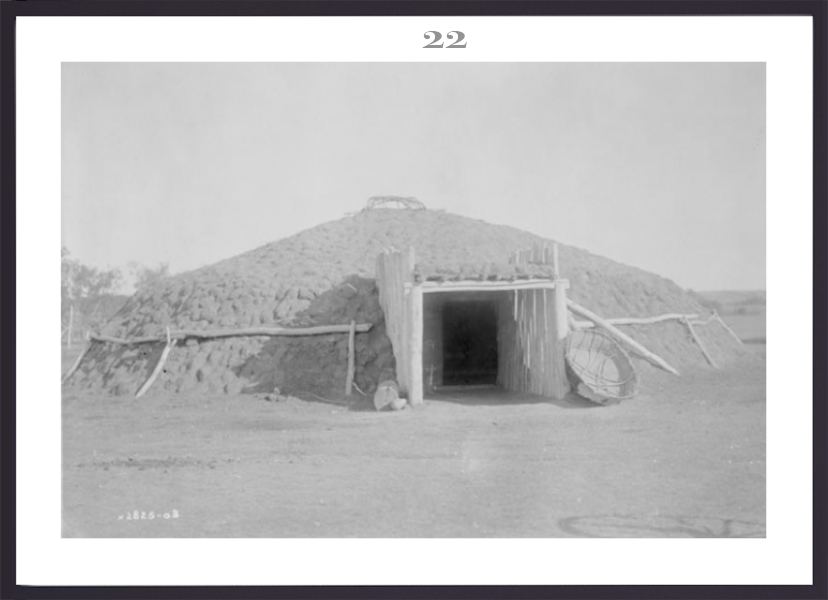

- Mandan earthen lodge Earthen lodge, with bull boat by doorway, North Dakota.

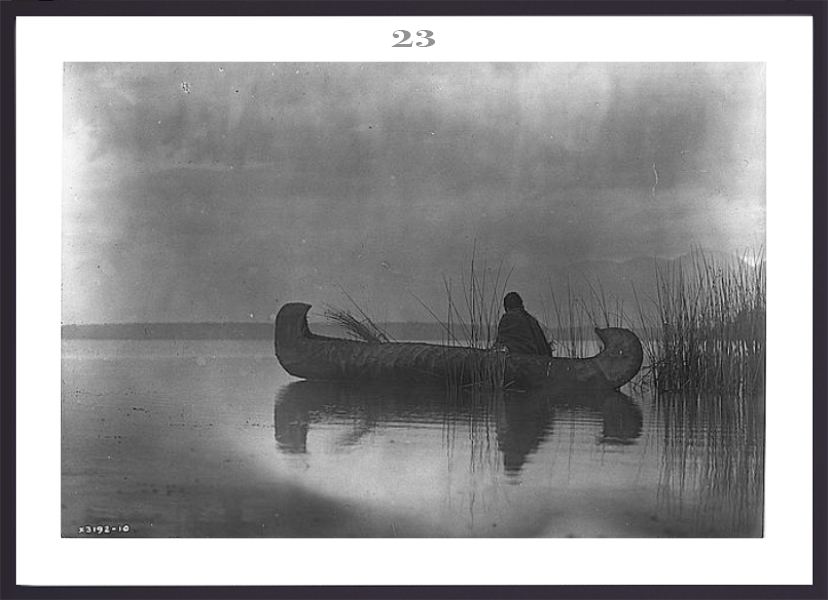

- Kutenai duck hunter Kutenai man seated in bow of canoe nestled in sparse rushes.

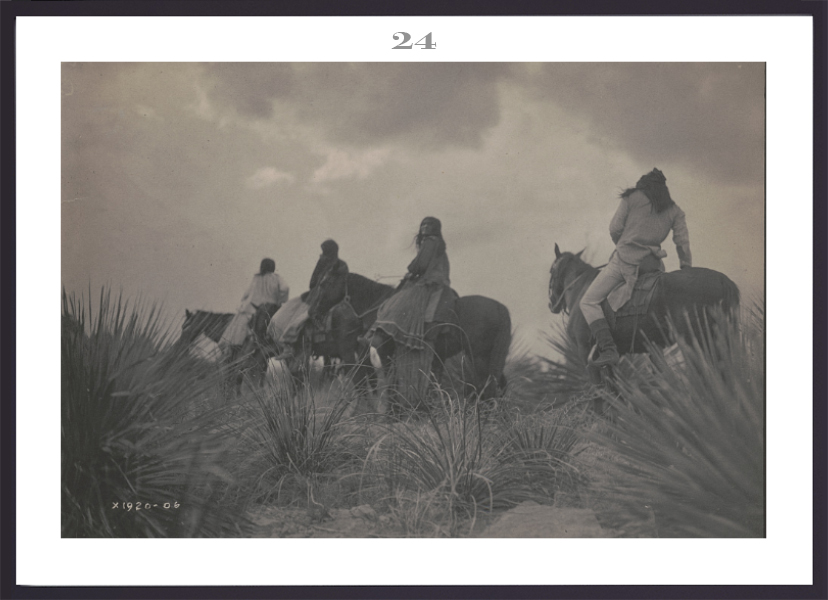

- Before the storm Four Apaches on horseback under storm clouds.

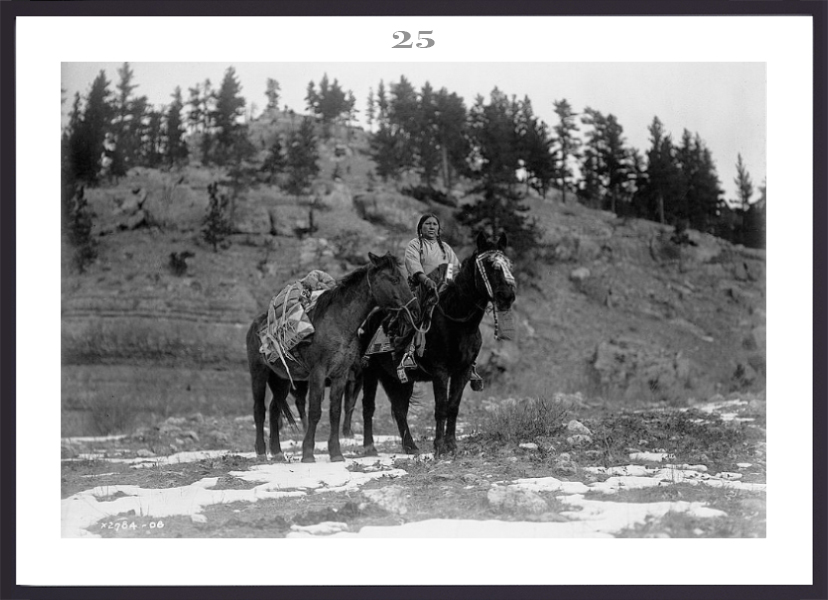

- Pack horse [i.e., packhorse]—Apsaroke

Point out and discuss: (Click on embedded links above to enlarge.) Comparing Catlin’s Indian Gallery and the Curtis Collection provides a vehicle for exploring the expressive potential of each media and the implicit Native American stereotypes these images reinforce and extend. Compare and contrast the two galleries. (To facilitate gallery comparisons it may be beneficial to toggle between galleries in separate tabs.) How does the Curtis Collection echo Catlin’s Indian Gallery? How are the two galleries different?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: Both artists offer compelling portraits of Native Americans who peer straight back at the viewer. The Curtis Collection shows more women and children and emphasizes familial relationships. Both artists seem to respect and honor their subjects. The unsmiling portraits in both galleries suggest Native Americans are a stoic, hardened people. (Native American writers in the literature links below suggest joy, humor, compassion, and spirituality are valued traits, yet they aren’t shown in these portraits.) Catlin’s titles and descriptions emphasize the individual, providing their Indian name and accomplishments. While some of Curtis’s titles include the subject’s names translated in English, he just as often generalizes the individual into a type. Both artists show Native Americans harvesting natural resources and emphasize their connection to nature. Catlin’s paintings highlight buffalo hunting and horsemanship. (The buffalo are almost extinct by the time Curtis picks up a camera.) Curtis’s photographs depict Native American industry as they gather a range of provisions. Both artists have a romanticized, nostalgic view of Native American culture that relegates their subjects to the past. They focus on the exotic, depicting “pure” Native Americans, ignoring, or minimizing, how indigenous people were successfully adapting to new political and material circumstances. This is especially the case with Curtis who doesn’t include Native American professionals, such as the writers, activists, and educators in the literature links below. (Focusing exclusively on the “traditional” perpetuates the vanishing race stereotype that saw Native Americans as just “savages” without a future.) In crafting his idealized narratives Curtis overlooks the institutional injustices Native Americans faced at the turn of the 20th century. Catlin’s Indian Gallery does include prisoners of war —Osceola and Black Hawk and his compatriots. These resistors could be seen as activists. (Did Catlin include them because they were sensational and would be a draw for his gallery or were they included to underscore his own sense of activism?)

Cap off this discussion by asking students, which is the more truthful medium, photography or painting? Why? Typically, with its real-world, moment-in-time focus, photography is seen as more truthful and painting is deemed more expressive. That is not the case here. Curtis has been criticized for re-envisioning Native Americans in their original environments. This included cropping out images of modernity, requesting his subjects wear traditional clothing that he sometimes provided, and emphasizing arcadian scenes of pastoral bliss. Curtis became expert at staging his photographs to tell small stories that were part of his larger romantic narrative of a lost way of life. Catlin, on the other hand, was not a trained artist and tended to paint exactly what he saw. For his portraits he would quickly paint his subjects’ faces and outline their other features to be completed back in his studio. (Further research on Edward Curtis’s life and work will help students find even more parallels with Catlin’s life and work.)

Matika Wilbur’s Project 562 extends this artistic tradition into the 21st century with some meaningful adaptations. Like Catlin and Curtis before her, Wilbur hopes to visit and depict tribes across the continent in order to raise awareness about contemporary Native American issues and to create a visual record of a proud and noble people. But, Wilbur, a photographer and storyteller of the Tulalip and Swinomish tribes, also intends to uproot some of the one-dimensional stereotypes Catlin’s and Curtis’s art perpetuates and model a more equitable and inclusive process for helping Native Americans tell their own stories.

Wilbur’s introductory blog post for Project 562 echoes the mission Catlin expressed almost 200 years before.

My goal is to unveil the true essence of contemporary Native issues, the beauty of Native culture, the magnitude of tradition, and expose her vitality. Did you know that there are 562 Federally recognized Tribal Nations in the United States? My goal is to create a publication and exhibition representing Native people from every tribe. But really, the ultimate goal is education. If you support Project 562, then together we can move a step closer toward abolishing negative stereotypes, honoring tradition, and leaving legacy. Starting in December of 2012, I will be hitting the road,… I will begin in Washington State, and work my way South through Oregon, Idaho, California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, until I have visited all 52 states, all 562 Federally Recognized Tribes in this nation. I will travel in my RV, fully equipped with a photographic studio, darkroom, and sleeping quarters.”

— Matika Wilbur, in the blog post that launched Project 562

Comparing and contrasting the Project 562 gallery with Catlin’s Indian Gallery is rich with opportunities for teachable discussions. The Project 562 gallery is not a record of a doomed people. Instead, students will see examples of vibrant, enduring traditions and individuals empowered by there cultural heritage. They will meet activists who live Native American values and fight for Native American rights, while also being proud contributing citizens of the United States. Yes, the portraits let you look into the eyes of people with stoic resolve, but you will also see their joy, their humor, their compassion, and their smiles. Encourage students to consider, not only Wilbur’s process and product, but how she shares her work with the public. This will help students better understand both her work and Catlin’s. Here are some links to get the conversation started.

- Changing the Way We See Native Americans, Matika Wilbur’s TED Talk. This links to other related TED Talks on YouTube.

- This gallery provides a glimpse into the 562 photographs and their backstory. Don’t miss the social media links.

- The 562 blog chronicles the multiyear journey and underscores Wilbur’s collaborative, relationship-building pocess. This post discusses the journey’s unwelcome traveling companion, Edward Curtis.

- The All My Relations podcasts explore different topic facing Native peoples today. This episode discusses cultural appropriation and Edward Curtis.

- A series of Project 562 films offer insight into the project and contemporary native American issues.

Think Like an Artist

Curate a meaningful gallery. Curators are like artists. They are sensitive to visual patterns and relationships. They make meaning from visual juxtapositions. Artworks are their medium. The Smithsonian American Art Museum and The Library of Congress allow viewers to easily download jpgs of individual paintings and photographs from Catlin’s Indian Gallery and the Curtis Collection. That gives students over 1500 images to work with. Have students create a thumbnail gallery of 7–10 favorite visuals or a group of images that explore a specific area of interest. Have students arrange their thumbnail gallery on a single page with careful consideration on how the images are organized. Also consider having students create a descriptive title for their gallery and labels with context-setting background information. Encourage students to share and discuss their gallery with the class.

Life Lesson

Great accomplishments = x% inspiration + x% perspiration + x% community support + x% luck In explaining that great accomplishments depend more on hard work than ingenuity, Thomas Edison said, “Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration.” On its surface Catlin’s career seems to follow this formula. Catlin was a marginal self-trained painter who made the most of his talents. Yes, he painted the magnificent Stu-mick-o-súks, Buffalo Bull’s Back Fat Head Chief, Blood Tribe (full frontal half-length portrait). But, he also painted the Ah-móu-a, The Whale, One of Kee-o-kúk’s Principal Braves (angled full-body portrait). Note the wee head on the giant body and, in particular, the unfortunate left hand. Catlin grappled with proportion and perspective. Catlin’s unrelenting sense of mission and uncompromising work ethic made up for his dearth of painterly talents. Throughout his career he used a tireless trial and error process to grow as an artist and a showman.

What this equation ignores is the good will Catlin was regularly afforded. Soliciting the help of others was one of Catlin’s greatest talents. His extended family helped him finance and exhibit his work. Complete strangers, such as General William Clark provided guidance and helped Catlin join expeditions to the frontier. And countless Native Americans opened their lives to him, sharing their time, artifacts, and sacred ceremonies while asking little in return. Would the Indian Gallery have existed without their selfless support?

Catlin’s career suggests that good fortune should also be factored into Edison’s equation. If Catlin had been successful in selling his Indian Gallery to Congress in 1839 it would have been lost in the 1865 fire that swept through the Smithsonian destroying the Stanley Indian Gallery of portraits. In addition, that fire created a demand for Catlin’s work that saved the Indian Gallery from a dank, rodent-infested basement where the paintings were deteriorating. In this unexpected window of opportunity rests Catlin’s legacy. A few years either way and his life’s work—and reputation—may have been lost.

If Catlin’s career offers any life lessons, it may be to embrace inspiration, hard work, and the humility to recognize the importance of community support and luck. It’s up to you to figure out the percentages in your own personal formula for success.

Related Video and Multimedia Resources

- PBS Learning Media’s Black Hawk and Catlin Native Americans Then and Now Studies (5:45) introduces Catlin’s paintings through the perspective of contemporary Native Americans. They discuss how these painting and Black Hawk’s ledger drawings serve as important historical documents but they also remind the viewer that Native cultures grow and change like all vibrant cultures.

- George Catlin’s Indian Portraits (2:18) is an excerpt from the PBS Civilizations series. This excerpt introduces Catlin and touches on the controversy around his work.

- Lee Stillman’s lecture for the Montana Historical Society George Catlin: First Artist Up the Missouri River (52:53) chronicles Catlin’s life and work. It provides background information and an honest appraisal of Catlin’s artistic talents that teachers may value. This is likely too academic for classroom use. (Occasional audio glitches)

- Dances With Wolves – the buffalo hunt scene (6:00) seems to draw on Catlin’s paintings in its depiction of the Lakota and how they hunted buffalo (see #415 Buffalo Chase above). Just as Catlin viewed himself as a savior, the scene ends with the great white hunter saving the day.

- New Moon Wolf Pack Auditions!!!! (7:06) uses satire to skewer common Native American stereotypes perpetuated in Catlin’s work and other mass media and defies Catlin’s depiction of a stoic people devoid of humor.

- Smoke Signals Movie Clip: How to Be a Real Indian (2:41) is an excerpt from the first feature film written, directed, and produced by Native Americans. In this clip two contemporary Native Americans discuss how they feel compelled to conform to ill-fitting Native American stereotypes. This humorous and nuanced exploration of contemporary Native American culture speaks to themes discussed above.

Integrating into Your Curriculum

Artists oftentimes use common visual strategies or signposts to alert viewers to significant details in their art. Here are some ideas for using these visual signposts to unpack a work of art. Remember, the close reading skills in art appreciation are similar to the close reading practices taught in reading.

The Smithsonian American Art Museum offers an extensive array of educational resources and practical teacher support. In particular, George Catlin and His Indian Gallery – Classroom Activities offers an especially comprehensive set of teaching plans that incorporate primary source materials that complement the artworks and writings of George Catlin. The lesson plans are arranged in four sections: Catlin’s Quest: Choices and Consequences, Ancestral Lands, The Western Landscape, and Chiefs and Leaders. Campfire Stories with George Catlin–An Encounter of Two Cultures (2002) which predates the lesson plan collection above is not as complete or refined but can be mined for additional teaching ideas.

Literature Links: What piece of literature would you partner with George Catlin’s Indian Gallery? The portraits from the Indian Gallery offer a number of avenues for literary exploration.

Catlin’s Exploits and Exploitations: Catlin was as prolific a writer as he was as an painter. With the eloquence of a lawyer, the attention to detail of an artist, and the sense of drama of a showman, Catlin chronicled his exploits on the frontier in books and periodicals. Drum roll please for an awesome treat. Through their generosity and foresight, the HathiTrust Digital Library and the Internet Archive offer the following titles completely free.

- Photostatic copies from the New York Commercial Advertiser of letters by George Catlin describing the manners, customs, and conditions of the North American Indians. (1832–1839). Catlin’s first writings on his exploits on the American frontier were letters to the New York Commercial Advertiser. This text pulls all of these letters together into one downloadable pdf. These have the immediacy of news accounts. In places the print breaks up and is unreadable.

- North American Indians: being letters and notes on their manners, customs, and conditions, written during eight years’ travel amongst the wildest tribes of Indians in North America, 1832-1839 Volume 1 and Volume 2 (1842) Four decades after his initial sojourns Catlin published his Commercial Advertiser letters in a two volume set that includes 75+ sketches, notes, and certificates of authenticity from eyewitnesses. Time and distance give added nostalgia and edge to Catlin’s writing. He is especially critical of unfair government practices and unscrupulous trading practices, especially the use of alcohol to manipulate the Native American. These are organized, comprehensive and visually easy to read.

- Catlin’s notes of eight years’ travels and residence in Europe with his North American Indian collection. With anecdotes and incidents of the travels and adventures of three different parties of American Indians whom he introduced to the courts of England, France and Belgium Volume 1 1848. Catlin, George, 1796-1872. Volume 2 These autobiographical accounts show that Catlin was as ardent in promoting his Indian Gallery as he was in creating it. These volumes mark his shift from advocate to entertainer and from artist to showman. The reception the Indian Gallery receives vividly chronicles European views of Native Americans and the American West. In addition to relaying a bizarre story about “a jolly fat dame” (chapters 14 and 15), Volume 1 includes media reviews of the Indian Gallery and a copy of the Gallery’s descriptive catalog. That Volume 2 fails to acknowledge Catlin’s silent partnership with the notorious con artist P. T. Barnum, when he toured with 14 Iowa Indians, underscores that Catlin is not a reliable narrator and how far he transgressed from his original lofty mission.

Catlin’s earliest writings express his genuine excitement, wonder, and discovery as he shares his experiences with North America’s indigenous cultures. In working with publishers to create student editions, the undercurrent of paternalism in his writing becomes more pronounced. His escapades become more contrived and his exploits more sensational. He tends to focus on, and may even inflate, the exotic and strange at the cost of understanding. At what point does observation give way to exploitation? He wouldn’t be the first artist to compromise his intentions in order to live a little easier. So, you decide how deep to go into the Catlin library, but these three titles are related—and free. (Just because someone left baked goods in the teacher’s room doesn’t mean you should eat them.)

- The Boy’s Catlin. My Life among the Indians (1909). This is a young readers’ condensed version of Catlin’s original letters and notes. This condensed version includes a biographical sketch, 16 illustrations, and is not “susceptible to the moods of the artist.”

- Last Rambles amongst the Indians of the Rocky Mountains and the Andes (1868). Catlin considers this book an extension of his letters and notes as he moves beyond the plains to the “pine-dressed mountains and shores of the Pacific Ocean.” But, did this really happen? Some Catlin biographers challenge the veracity of these accounts. Remember what I wrote above about Catlin not being a reliable narrator.

- Life Among the Indians (187?). This book condenses Catlin’s writings on North American Indians “which will be of most interest to the public” into one book that also includes his experiences in Central and South America. That this book opens with sensational and stereotypical chapters titled “Indian Warfare—Scalps and Scalping” and “Medicine Men—Drawing Fire from the Sun” shows how far Catlin strayed from his original educational mission. The chapter on scalping is a study in pandering to the most vulgar aspects of the marketplace. The title is phrased like clickbait, but the contents extoll Native American sense of honor and minimize the practice.

NOTE: In his writing Catlin regularly uses the term squaw to describe Native American women. Today we are more enlightened about the origin and power of such a term. As Wikipedia explains, “The English word squaw is an ethnic and sexual slur, historically used for Indigenous North American women. Contemporary use of the term, especially by non-Natives, is considered offensive, derogatory, misogynist and racist. The English word is not used among Native American, First Nations, Inuit or Métis peoples.” Caution students not to use the term in their discussions or writings. Learn more about term here

See the Paleface through Native American Eyes: While Catlin strove to chronicle Native American customs and values, it is through a white man’s eyes. Native American writers from the same time period and region help us to see from the other side of Catlin’s canvas. These writings from Native American authors give voice to the people Catlin’s Indian Gallery largely overlooked—women, children, and commoners—and describe the role government officials, unscrupulous traders, alcohol, missionaries, and boarding schools played in the oppression of Native American cultures. Native American literature from the time period also refutes the stereotype of uneducated savages.

- Chief Andrew Blackbird, Complete both early and late history of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan, a grammar of their language, personal and family history of author (1897). The fourteen chapters in this book cover a broad array of Ottawa and Ojibwa (Chippewa) life including a pre-contact history of the people; a description of their traditions, cultural practices, and legends; and an accounting of how the natives have suffered at the hands white settlers and the United States government. This book also includes Christian prayers translated by the author and a basic grammar of the Ottawa and Ojibwa languages.

- Jane Johnston Schoolcraft (Bamewawagezhikaquay) wrote under the pseudonyms Leelinau and Rosa for The Literary Voyager, or, Muzzeniegun (1826–1827). These writings offer a direct connection to Catlin’s Indian Gallery. Jane Johnston, an Ojibwa Indian, married Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Indian agent and scholar. While Henry initially supported Catlin, and even wrote a testimonial endorsing his Letters and Notes, he eventually became a rival and vocal critic. Having spent 30 years on the frontier, he disparaged Catlin as a “tourist” for his summer ventures. Schoolcraft explored different ways to share his study of Native American ways. With his wife he created a manuscript magazine that described all facets of Chippewa life and culture. These are Jane’s writings, but don’t overlook neighboring articles written by a range of authors: “The Origins of the Robin: An Oral Allegory,” pages 37–39; “Moowis, The Indian Coquette: A Chippewa Legend,” pages 56–57; Mishosha, or the Magician and His Daughters: A Chippewa Tale or Legend,” page 93–71; “Lines to a Friend Asleep,” page 71*; “Lines Written Under Affliction,” pages 84–85*; “Lines Written Under Severe Pain and Sickness,” page 97*; “Invocation to My Maternal Grandfather on Hearing His Descent from Chippewa Ancestors Misrepresented,” pages 142–143*; “To My Ever Beloved and Lamented Son William Henry,” pages 157–158* (*=poems)

- Ohiyesa’s (Charles Alexander Eastman) Indian Boyhood (1902). This autobiography chronicles Charles Eastman’s early childhood as a Santee Sioux in the mid-1800s. It opens with Eastman’s birth in a buffalo hide tipi in the winter of 1858. This is followed by a child’s view of the Sioux Uprising in Minnesota that sent Eastman’s family into exile in Canada. He goes on to describe the rich traditional life of the Santee Sioux children including an Indian boy’s training, childhood games, and legends told around a campfire. He explains in detail how his early education in a mission day school forced his assimilation into white civilization.

- Zitkala-Sa’s (Gertrude Simmons Bonnin) American Indian Stories (1921). This autobiography describes Gertrude Bonnin’s childhood. Her stories are rich with the values and customs she lived as a Yankton Dakota Sioux during the 1880s and the cultural misunderstandings she experienced in boarding school and the injustices inflicted on her family by government officials. On page 79, she expresses the rage she feels when racist students, jealous of her academic success, taunt her with the word “squaw.” She describes how education was used to both oppress and empower her and other Native American children.

- Ohiyesa’s (Charles Alexander Eastman) Old Indian Days (1907). These are 15 short stories from a Sioux perspective. “The Chief Soldier,” “The Famine,” and “The White Man’s Errand” describes the Minnesota Uprising of 1862, an event Eastman experienced firsthand. Half of the stories involve women protagonists. Eastman was one of the first authors to accurately depict the important role women played in Sioux society. “Winona, The Woman-Child” and “Winona, The Child-Woman” describe the training of a Sioux girl. “The Peace-Maker” tells the story of a Sioux woman’s bravery against the enemies of her people— warriors from the Sac and the Fox tribes and alcohol. “The War Maiden” details the exploits of a woman warrior. These and other stories vividly describe Sioux values, customs, and social practices.

- Sarah Winnemucca Hopkins’ Life among the Piutes, Their Wrongs and Claims (1883). While this involves indigenous people who lived further west than Catlin originally traveled, this is too significant a book to not include here. Quickly written and printed with the support of two women activists in Boston, this book was created to influence pending federal legislation. The first two chapters “First Meeting of Piutes and Whites” and “Domestic and Social Moralities” compliment the writings in this list with their exploration of Piute customs and beliefs and their distrust of white people. The later chapters are searing and can be graphic, so consider their appropriateness for students. The reader will come away wondering who the “savages” really are.

- Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh (George Copway’s) The life, history, and travels, of Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh (George Copway), a young Indian chief of the Ojbwa nation, a convert to the Christian faith, and a missionary to his people for twelve years (1846). This autobiography is offered here with a caveat. Even though the time period and the region align with Catlin’s Indian Gallery, Copway writes from the perspective of an Indian who experienced Christian conversion. The opening line echoes the missionaries’ contempt for Native American culture, “The Christian will no doubt feel for my poor people, when he hears the story of one brought from that unfortunate race called the Indians.” He goes on to describe how his people lived in darkness, awaiting God’s light. Even with this undercurrent of penitence, the early chapters on Ojibway life and his references to traders as land-sharks and how the whites plied the natives with whiskey is eye opening.

Revealing Reviews: Book reviews of George Catlin’s North American Indians: Letters and Notes expose common Native American stereotypes harbored by non-natives. Then, select pairings offer alternative perspectives and highlight flaws in reasoning.

- “Vindication of the United States” (review) [Volume 11, Issue 4, Apr 1845; pp. 202-211] Southern literary messenger. This book review expresses a righteous indignation toward Catlin’s beliefs and disdain for Native Americans. This is not intended as a false equivalence for a debate on westward expansion. So, in all that is holy, please do not teach it as such. Rather, this review vividly evokes a prevailing historical mindset that used a warped view of Christianity to fuel American imperialism and justify unjust Native American removal policies. Published the same year Manifest Destiny was coined and 30 years before Social Darwinism was popularized, the sentiments of both find voice here. Too expose the review’s bias, consider having students color code references to providential purpose, cultural superiority, and white supremacy. Listing how this review characterizes Native Americans versus European pioneers can likewise expose the writer’s bias. While Manifest Destiny and Social Darwinism have been discredited, echoes of these arguments are still heard today when gas pipelines are being imposed on sacred lands and lumbermen attack indigenous peoples in the Amazon. This may be a worthwhile exercise to help students think how they want to respond to these perspectives.

- Art VI (Letters and Notes Book review) The Edinburgh Review: Or Critical Journal, Volumes 74, Jan 1842; pp. 415–430. Adopting Catlin’s “progressive” outlook, this review marvels at Catlin’s exploits and the “doomed” Native American cultures but fails to recognize the role government policies and unscrupulous trading practices played in the oppression of Native Americans. “Civilization” is viewed as inevitable and not something the simple natives could comprehend and leverage. Smallpox and alcohol abuse, while recognized as devastating, just happen. While this review celebrates Native Americans as “noble savages,” it shares many of the assumptions in the Vindication review. Applying the color-coding exercise from the previous review here can help students see the overlapping assumptions and shared bias in these perspectives. For concise reviews of the Indian Gallery that echo this perspective, see Catlin’s notes of eight years’ travels and residence in Europe pages 205–245.

- Ohiyesa’s (Charles Alexander Eastman) The Indian Today: The Past and Future of the First American (1915). While not a review of Catlin’s Letters and Notes, Eastman’s text directly refutes the arguments in “Vindication.” Note especially the first three chapters. They provide an overview of Indian “character and motives” and how unscrupulous traders and the military used these values to manipulate the indigenous people. He describes how civilizers brought alcohol and social behaviors that introduced diseases that corrupted and weakened native communities. Chapter II, “The How and the Why of Indian Wars,” challenges the sanitized histories in traditional textbooks. Chapter III, “The Agency System: It Uses and Abuses,” documents the devastating results of ill-conceived government policies toward the Indians.

- “Vindication of the United States” contorts Christian beliefs to justify the taking of land and the destruction of Native American cultures. Laudato Si, Pope Francis’ encyclical on the environment and human ecology offers an illuminating pairing that speaks to the environment and social justice issues from the same Christian lens with a wholly different outlook. Especially see Section V Global Inequality “Today, however, we have to realize that a true ecological approach always becomes a social approach; it must integrate questions of justice in debates on the environment, so as to hear both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor.…Inequity affects not only individuals but entire countries; it compels us to consider an ethics of international relations.” This pairing reminds us that the treatment of Native American communities doesn’t just lay at the feet of past generations. Native Americans are not a vanishing race. While many may share Catlin and Curtis’s lofty ideals, if we don’t learn from their mistakes, we too are doomed to repeat them.

Representing and Re-presenting Native Americans: Who should represent Native Americans to the broader world? As George Catlin set out to exhibit his Indian Gallery on the East Coast and in Europe, he believed the answer to that question was him. He had, after all, spent six summers painting select members of 48 tribes. While his answer is clearly suspect, his gallery and his efforts to promote it provide an ideal forum to explore this question. These pairings explore a question that is as relevant for artists, educators, museum curators, ethnographers, and the media today as it was more than a century ago.

- Catlin’s notes of eight years’ travels and residence in Europe with his North American Indian collection. With anecdotes and incidents of the travels and adventures of three different parties of American Indians whom he introduced to the courts of England, France and Belgium Volume 1 and Volume 2 (1848). These autobiographical accounts chronicle how Catlin’s intentions evolved, eventually becoming an art-free Wild West show that perpetuated some negative Native American stereotypes. These shows with both make-believe and real Indians set the stage for the even more outlandish Buffalo Bill Wild West Shows where Indians are set up as dastardly foils to the glorified American cowboy.

- Robert Lewis’ “Wild American Savages and the Civilized English: Catlin’s Indian Gallery and the Shows of London” in the European Journal of American Studies, Spring 2008. This journal article offers a concise history of how Catlin’s intentions evolved as he strove to capture market share. Lewis shows how Catlin’s intentons shifted from academic ethnographic presentations to romanticized tableau vivants to inflammatory reenactments full of theatrical scalpings and war hoops by costumed Londoners with thick cockney accents. Encourage students to consider this spectrum of representation and how even the best of intentions can be distorted in trying to respond to the market’s lowest common denominator.

- David R. M. Beck, Professor of Native American Studies at the University of Montana, in Missoula, “Fair Representation? American Indians and the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition.” This journal article describes how the representations of American Indians at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair fall into five categories: Indians as objects of science, Indians as assimilating into American society, Indians as romantic images and actors reflecting a bygone era, Indians as savage or wild representations of America’s past, and Indians as they wanted themselves to be known and understood. Catlin’s Indian Gallery reenactments and tableau vivants could be categorized along the same lines. This pairing presents an opportunity to consider the various goals in representing Native Americans to the non-Native world and who should establish those goals.

- Pokagon, Simon, 1893. The Red Man’s Rebuke, World’s Columbian Exposition (1893: Chicago, Ill.). This treatise by author and activist Simon Pokagon confronts the intended white reader with a scathing account of the pain and suffering the “pale-faces” imposed on Native Americans. Written to protest the fact that no Indians were invited guests at the opening of the Chicago exposition, this booklet struck a popular nerve and secured Pokagon an invitation to be the guest of honor on “Chicago Day,” where he gave a much more conciliatory speech. Seen by some as a respected leader and others as a self-promoting charlatan, Pokagon reflects the challenge of being a single representative of a diverse group. This pairing encourages students to consider what it mean to be an authentic spokesperson?

Contemporary Artists Who Use Their Art to Explore and Present Their Native American Identity: These artists challenge common Native American stereotypes and provide insight into contemporary Native American beliefs and concerns. Consider having students present the work of individual artists in a way that explores their unique perspectives and shared interests.

Jim Denomie • Andy Everson • Jeffrey Gibson • Teri Greeves • Frank Buffalo Hyde • Zig Jackson • Brad Kahlhamer • Nadya Kwandibens • Meryl McMaster • Marianne Nicolson • Wendy Red Star • Josue Rivas • Cara Romero • Matika Wilbur • Will Wilson

History/Social Studies: As this unit of study establishes, Catlin tended to focus on male tribal leaders and their families. They had the most opulent attire and their acceptance of Catlin’s undertaking established trust and opened doors with others in the tribe. This focus on tribal leaders presents avenues for further historical study. Catlin sets a context for many of his paintings in his book North American Indians: being letters and notes on their manners, customs, and conditions, written during eight years’ travel amongst the wildest tribes of Indians in North America, 1832-1839 Volume I and Volume 2 (1842). Use the books’ pdf search function to research the people depicted in the portraits with an eye toward further exploration. The following research opportunity on the Black Hawk War offers a case in point. Note: The Luce Center labels for each painting on the Smithsonian American Art Museum website highlights these and other references. Also, see the 1885 National Museum report for unparalleled insight into individual paintings in the Indian Gallery.

The Black Hawk War: Catlin’s Indian Gallery opens with a portrait of Black Hawk and his supporters. (Catlin also paints a rival faction within the Sauk tribe, Kee-o-kuk and his family members and supporters. Comparing these groups of portraits reveal Catlin’s sympathies for Black Hawk. An 1885 National Museum report offers great insight into the backstory for these paintings—see pages 326–358.) As Catlin explains in his original exhibition catalog, he painted their portraits in 1832 when they were prisoners of war at Jefferson Barracks. The Black Hawk War offers an ideal forum for further research since it encapsulates a common pattern of conflict that arose as European settlers encroached on Native Americans lands; it becomes a justification for the Indian removal policies and the establishment of the reservation system; it shows how the negative stereotype of Native Americans as blood thirsty and war-like was perpetuated; and it introduces key figures before they assumed their significant roles on the historical stage, these include Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis. Here are some resources to begin your research.

- Autobiography of Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak, or Black Hawk, … Black Hawk, Sauk chief, 1767-1838. It is said that the victor gets to write the history of a conflict. That is not the case with Black Hawk. This autobiography tells the history of the conflict from his perspective. He might have been captured, but he continued to advocate for Native American rights. He details how the cultural misunderstandings, personal betrayals, and broken treaties heightened hostilities. He also describes how the tribes were used as pawns in international conflicts. In addition, he describes how the people on the East Coast received him and his council as celebrities and how the government used tours of major East Coast cities to intimidate native leaders from further uprisings.

- Wisconsin Historical Society’s site Turning Points in Wisconsin History: The Black Hawk War This online resource offers an overview of the conflict and links to a raft of related historical documents.

- Ellen Whitney’s The Black Hawk War, 1831–1832 Volume I, Illinois Volunteers. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Historical Library, 1970 This history opens with a comprehensive overview of the war and then offers a wealth of primary source documents.

How would you use this gallery to build on one of your units of study? Please share if you have other ideas on how to teach George Catlin’s Indian Gallery as an English/language arts lesson plan.

Catlin’s Creed: I love a people

I love a people that have always made me welcome to the very best that they had.

I love a people who are honest without laws, who have no jails and no poorhouses.

I love a people who keep the commandments without ever having read or heard them preached from the pulpit.

I love a people who never swear or take the name of God in vain.

I love a people “who love their neighbors as they love themselves”

I love a people who worship God without a Bible, for I believe that God loves them also.

I love a people whose religion is all the same, and who are free from religious animosities.

I love a people who have never raised a hand against me, or stolen my property, when there was no law to punish either.

I love and don’t fear mankind where God has made and left them, for they are his children.

I love a people who have never fought a battle with the white man, except on their own ground.

I love a people who live and keep what is their own without lock and keys.

I love a people who do the best they can. And oh how I love a people who don’t live for the love of money.

I have designed to get portraits of several distinguished and well selected Indians of both sexes, from every tribe of Indians of both sexes, from every of Indians in North America, painted in their native costumes, accompanied with pictures representing their villages, domestic habits, amusements, and the landscape of the country they inhabit, with as much anecdote of their lives as I can obtain and attach to them. I have already been more than a year engaged in the undertaking, and have obtained more than 200 portraits.…I resolved to make the collection myself, which I am doing at great expense, sacrificing the society of my deepest friends, and necessarily putting my life more or less in jeopardy for the accomplishment of my object—If I should live to accomplish my design, the result of my labours will, doubtless, be interesting to future ages, who will have nothing else left from which to judge of the original habits of that noble race of beings, who require but a few years more of the march of civilization and death to deprive them of all their native customs and character.

—George Catlin, New York Commercial Advertiser, July 24, 1832

I closely applied my hand to the labours of the art for several years; during which time my mind was continually reaching for some branch or enterprise of the art, on which to devote a whole lifetime of enthusiasm; when a delegation of some ten or fifteen noble and dignified-looking Indians, from the wilds of the “Far West,” suddenly arrived in the city, arrayed and equipped in all their classic beauty,—with shield and helmet,—with tunic and manteau,—tinted and tasselled off, exactly for the painter’s palette!

In silent and stoic dignity, these lords of the forest strutted about the city for a few days, wrapped in their pictured robes, with their brows plumed with the quills of the war-eagle, attracting the gaze and admiration of all who beheld them. After this they took their leave for Washington City, and I was left to reflect and regret, which I did long and deeply, until I came to the following deductions and conclusions.

Black and blue cloth and civilization are destined, not only to veil, but to obliterate the grace and beauty of Nature. Man, in the simplicity and loftiness of his nature, unrestrained and unfettered by the disguises of art, is surely the most beautiful model for the painter.…The history and customs of such a people, preserved by pictorial illustrations, are themes worthy the lifetime of one man, and nothing short of the loss of my life, shall prevent me from visiting their country, and of becoming their historian.

…with a light heart, inspired with an enthusiastic hope and reliance that I could meet and overcome all the hazards and privations of a life devoted to the production of a literal and graphic delineation of the living manners, customs, and character of an interesting race of people, who are rapidly passing away from the face of the earth—lending a hand to a dying nation, who have no historians or biographers of their own to portray with fidelity their native looks and history; thus snatching from a hasty oblivion what could be saved for the benefit of posterity, and perpetuating it, as a fair and just monument, to the memory of a truly lofty and noble race.…

I set out on my arduous and perilous undertaking with the determination of reaching, ultimately, every tribe of Indians on the Continent of North America, and of bringing home faithful portraits of their principal personages, both men and women, from each tribe, views of their villages, games, etc., and full notes on their character and history. I designed, also, to procure their costumes, and a complete collection of their manufactures and weapons, and to perpetuate them in a Gallery unique, for the use and instruction of future ages.…

I have visited forty-eight different tribes, the greater part of which I found speaking different languages, and containing in all 400,000 souls. I have brought home safe, and in good order, 310 portraits in oil, all painted in their native dress, and in their own wigwams; and also 200 other paintings in oil, containing views of their villages—their wigwams—their games and religious ceremonies—their dances—their ball plays—their buffalo hunting, and other amusements (containing in all, over 3000 full-length figures); and the landscapes of the country they live in, as well as a very extensive and curious collection of their costumes, and all their other manufactures, from the size of a wigwam down to the size of a quill or a rattle.…

The world know generally, that the Indians of North America are copper-coloured, that their eyes and their hair are black, etc.; that they are mostly uncivilised, and consequently unchristianised; that they are nevertheless human beings, with features, thoughts, reason, and sympathies like our own; but few yet know how they live, how they dress, how they worship, what are their actions, their customs, their religion, their amusements, etc., as they practice them in the uncivilised regions of their uninvaded country, which it is the main object of this work, clearly and distinctly to set forth.…

The Indians of North America, as I have before said, are copper coloured, with long black hair, black eyes, tall, straight, and elastic forms—are less than two millions in number—were originally the undisputed owners of the soil, and got their title to their lands from the Great Spirit who created them on it,—were once a happy and flourishing people, enjoying all the comforts and luxuries of life which they knew of, and consequently cared for;—were sixteen millions in numbers, and sent that number of daily prayers to the Almighty, and thanks for His goodness and protection. Their country was entered by white men, but a few hundred years since; and thirty millions of these are now scuffling for the goods and luxuries of life, over the bones and ashes of twelve millions of red men; six millions of whom have fallen victims to the small-pox, and the remainder to the sword, the bayonet, and whiskey; all of which means of their death and destruction have been introduced and visited upon them by acquisitive white men; and by white men, also, whose forefathers were welcomed and embraced in the land where the poor Indian met and fed them with “ears of green corn and with pemican.” Of the two millions remaining alive at this time, about 1,400,000 are already the miserable living victims and dupes of white man’s cupidity, degraded, discouraged, and lost in the bewildering maze that is produced by the use of whiskey and its concomitant vices; and the remaining number are yet unroused and unenticed from their wild haunts or their primitive modes, by the dread or love of white man and his allurements.

It has been with these, mostly, that I have spent my time, and of these, chiefly, and their customs, that the following Letters treat. Their habits (and theirs alone) as we can see them transacted, are native, and such as I have wished to fix and preserve for future ages.

— George Catlin, in the introduction of his North American Indians: Being letters and notes on their manners, customs, and conditions, written during eight years’ travel amongst the wildest tribes of Indians in North America, 1832–1839

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.