Teach close reading skills, the power of particulars, and America’s enduring spirit with Georgia O’Keeffe’s Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue

Cow Skull: Red, White, and Blue is part of The Met’s collection. See their website for detailed information. Click on the painting for a high quality image.

Cow Skull: Red, White, and Blue is part of The Met’s collection. See their website for detailed information. Click on the painting for a high quality image.

As I was working I thought of the city men I had been seeing in the East. They talked so often of writing the Great American Novel — the Great American Play — the Great American Poetry. People wanted to “do” the American scene. I had gone back and forth across the country several times by then, and some of the current ideas about the American scene struck me as pretty ridiculous. To them, the American scene was a dilapidated house with a broken down buckboard out front and a horse that looked like a skeleton. I knew America was very rich, very lush…Well, I started painting my skulls around this time.…I had lived in the cattle country—Amarillo was the crossroads of cattle shipping, and you could see the cattle coming in across the range for days at a time. For goodness’ sake, I thought, the people who talk about the American scene don’t know anything about it. So, in a way, that cow’s skull was my joke on the American scene, and it gave me pleasure to make it in red, white, and blue.

— Georgia O’Keeffe, describing the genesis of her painting in an exhibition catalogue

I painted my cow’s head because I liked it and in its way it was a symbol of the best part of America I had found. Cattle were important to America, as I knew from my days in Amarillo when they were only beginning to think about oil. I thought to myself ’Just for fun I will make it red, white, and blue–a new kind of flag almost.’ It always amused me as my idea of something American.

— Georgia O’Keeffe, in a letter to Anita Pollitzer, 1931

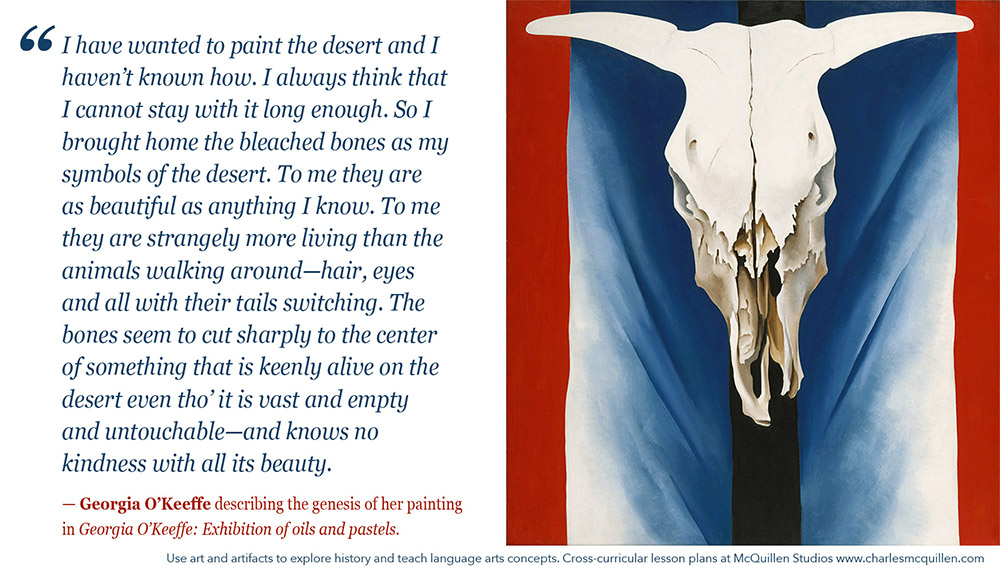

I have wanted to paint the desert and I haven’t known how. I always think that I cannot stay with it long enough. So I brought home the bleached bones as my symbols of the desert. To me they are as beautiful as anything I know. To me they are strangely more living than the animals walking around—hair, eyes and all with their tails switching. The bones seem to cut sharply to the center of something that is keenly alive on the desert even tho’ it is vast and empty and untouchable—and knows no kindness with all its beauty.

— Georgia O’Keeffe, “About Myself” in Georgia O’Keeffe: Exhibition of oils and pastels.

New York: An American Place; 1939

Look at Cow’s Skull: Red, White and Blue. Before reading the excerpt above, tell students the title of the piece and ask what is going on in this picture? This regional portrait has familiar imagery that is open to nuanced interpretations. See how much students can decipher through a group discussion. Encourage students to identify the evidence that supports their reasoning. Students should likewise be encouraged to share wonderings and voice confusions. As the conversation slows, explain you are going to read how the artists described the motivations and intentions that guided this painting. After reading the excerpts ask how does this new insight change your understanding of the painting?

Note: To facilitate discussion, you may want to introduce students to the term supraorbital foramen. Those are the two prominent holes above the cow’s eye sockets (human’s too) that channel the blood vessels and nerves to the forehead. Supra is from the Latin meaning “above or over.” Orbit is a medical term for the “bony socket of the eye.” Foramen is a medical term for a natural opening or passage, especially one into or through a bone.

Begin with art history

Georgia O’Keeffe was born in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin in 1887. The O’Keeffes impressed upon their seven children the need to be well educated. So, when Georgia expressed an interest in the arts her mother arranged art lessons with a local artist. Georgia continued to study art throughout her early schooling. To support her university studies and art making, O’Keeffe traveled around the United States working as a commercial artist and an art teacher. O’Keeffe was initially recognized for her nature studies and realistic painting techniques. In time she experimented with her own unique brand of abstract compositions.

In 1916 a friend of O’Keeffe shared a series of her abstract drawings with Alfred Stieglitz, an influential art dealer and photographer. Captivated by these drawings, Stieglitz immediately exhibited her work. Their shared interest in art grew into a deep personal relationship and, even though he was 23 years her senior, they married in 1924. Annual exhibits at Stieglitz’s galleries helped cement O’Keeffe’s reputation in the established art world. During this time period Georgia was best known for her large dramatically colored paintings of flowers. While her work and popularity flourished, Georgia resented the gender stereotypes and Freudian interpretations imposed on her work by patronizing art critics. Georgia expresses these frustrations in an exhibition catalog,

A flower is relatively small. Everyone has many associations with a flower — the idea of flowers. You put out your hand to touch the flower — lean forward to smell it — maybe touch it with your lips almost without thinking — or give it to someone to please them. Still — in a way — nobody sees a flower — really — it is so small — we haven’t time — and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time. So I said to myself — I’ll paint what I see — what the flower is to me but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it — I will make even busy New-Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers. Well — I made you take time to look at what I saw and when you took time to really notice my flower, you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower — and I don’t.

In 1929, feeling hemmed in by Stieglitz’s social circle and looking for a new source of inspiration for her work, O’Keeffe travelled with a friend to New Mexico. The landscape, architecture, and indigenous cultures refreshed her and refined her visual vocabulary. She witnessed Navajo rituals and traditions. She was immersed in the Catholic symbols and structures prevalent in the Hispanic communities. And, she experienced the Southwestern cowboy culture. Cow Skull: Red, White, and Blue grew out of these influences and evoked the contradictions inherent in American society as the affluence of the Roaring Twenties gave way to the Great Depression and an unforgiving Dust Bowl that ravaged the farms and ranches of the American Southwest. By integrating these cultural references into a expressive nature study, O’Keeffe melded naturalism and nationalism, creating an iconic portrait of America’s enduring spirit.

In blending realism and abstraction, O’Keeffe’s paintings brought majesty and spirituality to common natural objects—flowers, leaves, shells, stones, and bones. And while her simplified representations of New Mexico’s landscape and architecture aligned O’Keeffe with the regional art movement, her innovative style spoke to more universal modern art concerns and earned her the moniker the “Mother of American modernism.”

Look like an art critic

Cow Skull: Red, White, and Blue is part of The Met’s collection. See the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s website to learn more. For additional insight visit the Georgia O’Keefe Museum.

Comparing Realism and Abstraction

Nothing is less real than realism. Details are confusing. It is only by selection, by elimination, by emphasis, that we get at the real meaning of things.

— Georgia O’Keeffe

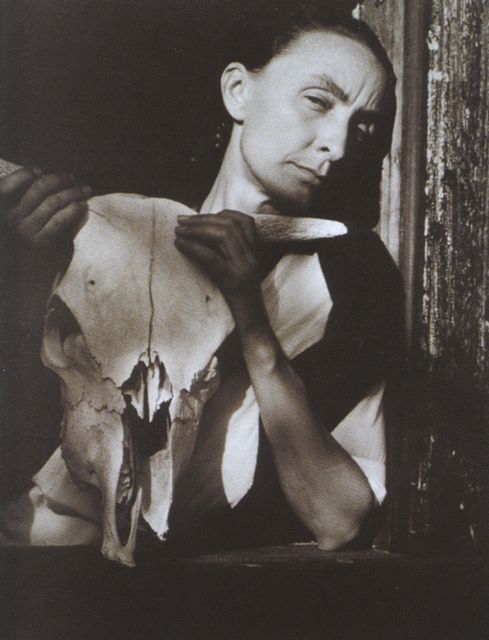

Point out and discuss: When O’Keeffe returned to New York with a barrel full of bones, her husband, Alfred Stieglitz, was as captivated by the skulls as O’Keeffe was and photographed Georgia with them. Compare O’Keeffe’s cow skull painting with the photograph of O’Keeffe holding the same cow skull. How is the rendering of the cow skull in the painting different than the cow skull shown in the photograph? How does O’Keeffe’s transformation of the cow skull provide added meaning?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: The painted skull is prominent and celebrated. It commands the composition looking directly at the viewer. The photographed skull is more of a prop, juxtaposed with Georgia. The painted skull appears more bleached and pristine, while the photographed skull has more shadows and seems gritty, like an historic relic. The painted skulls even, radiant lighting seems supernatural. The painted skull is elevated in the composition. Centered horizontally the skull’s horns reach out to the edges of the painting. The photographed skull rests heavy and low on the windowsill, off center, sharing space with Georgia. The elevated skull is more crucifix-like, sitting high on a cross with the horns extended like arms. This lighting and bearing makes the painted skull seem sacred. The painted skull is a sacred icon, while the photographed skull is a quaint artifact.)

Regional Imagery

Point out and discuss: Cow Skull: Red, White and Blue is layered with cultural associations—Native Americans, Hispanics, and cowboys. Have students review the historic and contemporary images in the gallery above and links below, and identify elements and references the painting may draw on.

- Images 1: Julian Martinez’ hide painting Buffalo Dancers (@1930s) shows how native cultures have traditionally used ceremonial animal masks. Click on this link to see videos of contemporary Cherokee Eagle Dancers.

- Images 2: Navajo chief’s wearing blankets are the most recognizable and prized of all Navajo weavings. They come in four phases. The First Phase pattern is composed of horizontal bands of alternating color at top, center, and bottom. Jalucie Marianito shows her contemporary first phase weaving. Here is a concise video tutorial on Navajo chief’s wearing blankets.

- Images 3 and 4: Early Spanish colonization introduced Catholicism to New Mexico. Religious symbols such as the crucifix and the cross are common in Hispanic communities.

- Images 5: Romantic visions of cowboy life inspired dude ranches throughout the west, including New Mexico. Symbols of the rugged “wild west,” including animal skulls, are common decorations from the earliest times to the present day. The early picture is of the Eaton brother’s and their families at Custer Trail Ranch in the Dakota Territory, one of the earliest dude ranches (1890). For a contemporary use of skulls see a cabin at the Granite Creek Ranch, a 6th generation working cattle ranch in the mountains of Eastern Idaho.

What southwestern cultural associations can you see in Cow Skull: Red, White, and Blue? How do these visual references add significance and meaning to the painting and how do they support O’Keeffe’s intentions?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: Like the ceremonial dancers who adopt an animal’s prominent features to create a spiritual connection, the painting makes the cow’s skull a sacred icon. The supraorbital foramen are depicted with dramatic shadows making them look like a second set of eyes. This double-eye effect is compounded by the china white forehead that sits on top of the darker fractured face. This evokes the mask the eagle dancer peers out from under. While the red, white, and blue coloring evoke the American flag, the stripes on the painting also call to mind the alternating bands on the Navajo Chiefs Blanket. The blue-white field with the diagonal lines look like the shadows on the blanket held out in the brilliant sun. The skull with the extended horns hovering on top of a black vertical band could be seen like a crucifix. In this light the forehead could be read as a torso and the supraorbital foramen as nipples. The dark vertical band with the prominent crack that splits the skull and the perpendicular lines created by the horns create a cross-like composition. The cow skull in the painting and the skulls on the dude ranches evoke romantic images of the Wild West, nostalgia for cowboy life, and the bountiful but unforgiving environment. On a dude ranch wall animal skulls hang as trophies, symbols of man’s conquest over nature. Together these shifting cultural elements evoke the complex societies of the southwest. They intertwine, creating a cohesive compelling image with a magical spiritual aura, much like the way Georgia saw the enduring American spirit.)

Expressive Oppositions

Point out and discuss: In creating her “Great American Painting,” O’Keeffe didn’t want to create a simplistic image of “a dilapidated house with a broken down buckboard out front and a horse that looked like a skeleton.” Rather, O’Keeffe recognized that a deep understanding of America meant you appreciated its layers and paradoxes, such as, a country of immigrants that loathed foreigners; a proudly democratic nation that actively restricted the voting rights of large sections of its citizenry; and an affluent society and a world superpower caught in the grips of a Great Depression. As a subject, the cow skull was open to varied, and even opposing interpretations. Have small groups of students select a pair of opposing terms from the list below and explain how they could both apply to Cow Skull: Red, White, and Blue—death/eternal; common/sacred; fragile/durable; specific/universal; small/monumental; and ugly/beautiful. How do these visual contradictions add significance and meaning to the painting and how do they support O’Keeffe’s intentions?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: Death/Eternal: The skull is a symbol of death, like a pirate’s flag or poison. The skull in the desert comes from a cow that died and then decomposed. The decomposition of the cow also touches on the eternal as it fits within the ongoing cycle of life as the cow is consumed by the land on which it fed. While the cow has died, its skull lives on as an artifact of the landscape and now as a work of art. Common/Sacred: The skull is common, evoking a typical domesticated animal. Cattle are grown like any other mass-produced food item. Skulls are a standard decoration in some cultural settings. It’s a natural occurring item almost akin to sticks and stones. The way O’Keeffe treats the skull makes it sacred. She makes the viewer reflect on it, imbuing it with added significance. It is elevated in a cross-like fashion. The pristine white of the skull is accentuated making it like a religious icon. These visual contradictions add complexity to the painting encouraging multiple levels of interpretation. As a portrait of America’s enduring spirit, the multiple interpretations evoke America’s own complexity and inherent contradictions.)

Think Like an Artist

My second year of high school, my brother and I lived with our mother’s younger sister in Madison. The art teacher was one of those thin bright-eyed women that I have always since associated with the idea of an Art Teacher. She wore her hat in school—a hat made all of artificial violets.…She is very vivid to me standing in front of the class—her hat of violets and a fresh spring feeling about her costume. Holding a Jack-in-the-pulpit high, she pointed out the strange shapes and variations in color—from the deep, almost black earthy violet through all the greens, from the pale whitish green in the flower through the heavy green of the leaves. She held up the purplish hood and showed us the Jack inside. I had seen many Jacks before, but this was the first time I remember examining a flower. I was a little annoyed at being interested because I didn’t like the teacher.…But maybe she started me looking at things—looking very carefully at details. It was certainly the first time my attention was called to the outline and color of any growing thing with the idea of drawing or painting it.

— Georgia O’Keeffe, in her autobiography

This lesson in magnifying and analyzing natural objects initiated an art practice that O’Keeffe employed throughout her career as she rendered flowers, shells, and bones. If it’s good enough for Georgia O’Keeffe why not give it a try. Encourage students to collect a small natural object of personal significance and then render it fully on a large surface noting and amplifying subtle shifts and details. Rolls of butcher paper with charcoal sticks or magic markers on a whiteboard will do—just work big. Challenge students to work like O’Keeffe and consider the abstract composition of the overall nature portrait, as well as its characteristic features.

Life Lesson

You paint from your subject, not what you see…I rarely paint anything I don’t know very well.

—Georgia O’Keeffe

Recognize the universal in the specific. Georgia O’Keeffe created universally appealing art from her deep personal experience with a specific locale. James Joyce expressed a similar desire to create from an intimate sense of place. “For myself, I always write about Dublin, because if I can get to the heart of Dublin I can get to the heart of all the cities of the world. In the particular is contained the universal.” Rosanne Cash echoed this sentiment in describing her album inspired by her travels in America’s Deep South, “The more specific you are about places and characters, the more universal the song becomes.” The poet Robert Pinsky takes an even more expansive view and contends that if you could understand an artifact or an idea well enough it would be a portal into the whole rest of the universe. These writers share the understanding that the more specific and concrete you are with your words and examples, the more relatable and far reaching your message can be. So whether you are in the expressive arts, building a brand, or promoting a cause, tell a memorable story with such personal conviction and detail that it taps into the universal.

Related Video

- Georgia O’Keeffe Talking about Her Life and Work (Part 1) (4:24) describes the motivations and influences that shaped her earliest bone paintings including Cow Skull: Red, White, and Blue.

- Georgia O’Keeffe: By Myself BBC Documentary 2016 (1:04:32) offers a comprehensive overview of O’Keeffe’s life and work with many historic images and firsthand accounts by Georgia, her family, and friends.

- Georgia O’Keeffe a Life in Art (13:39) is a documentary by the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum and offers a concise overview of O’Keeffe’s art and relationships.

Integrating into Your Curriculum

Artists oftentimes use common visual strategies or signposts to alert viewers to significant details in their art. Here are some ideas for using these visual signposts to unpack a work of art. Remember, the close reading skills in art appreciation are similar to the close reading practices taught in reading.

Literature Links: What piece of literature would you partner with Georgia O’Keeffe’s Cow Skull: Red, White, and Blue? Cow Skull: Red, White, and Blue could inform other regional literature from the time period.

- Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927) recounts the efforts of two rogue priests who abuse church tenets and the natives as they establish a diocese in New Mexico Territory. There are rich parallels in the way Cather marries journalistic objectivity with a subjective point of view and the way O’Keeffe marries realism and abstraction.

- Sanora Babb’s Whose Names are Unknown chronicles the struggles of the Dunne and Starwood families, High Plains farmers who fled drought dust storms during the Great Depression.

- N. Scott Momaday’s House Made of Dawn (1968) is a redemption story of a Pueblo Indian who loses his way after the traumas of World War II and uses traditional rituals to find his way back to the land and his culture.

- Frank Waters’ The Man Who Killed the Deer: A Novel of Pueblo Indian Life (1942) is the story of a rebellious Pueblo Indian haunted by the spirit of a deer he killed out of season (white law) and without ritual respect (native law). This story about sin and redemption explores Pueblo Indian values and their connection to the land.

Writing Opportunity: The Rule of Write About a Pebble. In his poem Paterson, William Carlos Williams wrote the now famous rallying cry of poets and artists alike, “Say it, no idea but in things.” In the way they both pursue this idea, master writing teacher Nancie Atwell and Georgia O’Keeffe prove to be kindred spirits. They both recognize the need to get beyond the general, and focus instead on specific observations and experiences. This lesson is based on Nancie Atwell’s lesson “The Rule of Write About a Pebble.”

Don’t write about a general idea or topic; write about a specific, observable person, place, occasion, time, object, animal, or experience. Its essence will lie in the sensory images the writer evokes: observed details of sight, sound, smell, touch, taste; and strong verbs that bring the details to life.

- Don’t write about ________(pebbles). Write about a ________ (pebble).

- Don’t write about fall. Write about this fall day. Go to the window; go outside.

- Don’t write about sunsets. Write about the amazing sunset you saw last night.

- Don’t write about dogs or kittens. Observe and write about your dog, your kitten.…

— Nancie Atwell, from her teaching resource Lessons That Change Writers.

Click this link to see how Georgia O’Keeffe’s Cow Skull: Red, White, and Blue can be used to teach elaboration and how to make the most of meaningful details.

How would you use this painting to build on one of your units of study? Please share if you have other ideas on how to teach Cows Skull: Red, White, and Blue by Georgia O’Keeffe as an English/language arts lesson plan.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.