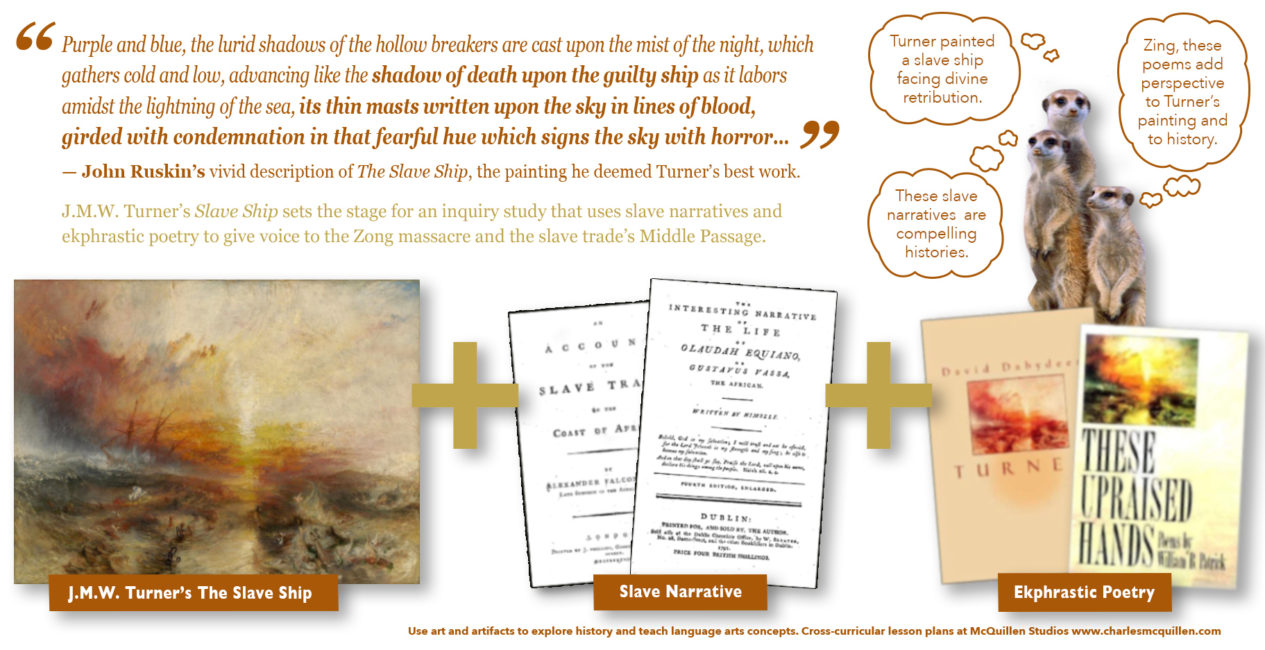

J.M.W. Turner’s The Slave Ship provides a compelling starting point for an inquiry study that combines the power of slave narratives and ekphrastic poetry to illuminate the Zong massacre and the brutal realities of the Middle Passage.

Turner’s The Slave Ship lays bare the Zong massacre and the unimaginable horrors of the Middle Passage. This inquiry study builds on that foundation, incorporating slave narratives and ekphrastic poetry to amplify the voices and perspectives of those who endured these atrocities. Turner’s painting, paired with these evocative poems, brings to mind President John F. Kennedy’s assertion: “When power corrupts, poetry cleanses, for art establishes the basic human truth which must serve as the touchstone of our judgment.”

The events surrounding the Zong massacre exemplify the devastating consequences of unbridled capitalism—when profits and wealth accumulation are prioritized over human rights. That Captain Collingwood’s actions were viewed as a “business decision” and later upheld by the courts only deepens the horror. Through this inquiry study, students will examine the basic human truths revealed by the Middle Passage and explore how these truths resonate in discussions of contemporary racism, human rights, and the ethics of unchecked capitalism.

Before launching an inquiry study it is important to have students experience a work of art on their own terms. Use this opportunity to build background knowledge, engage empathy, and spark wonderings. This link offers teaching moves and language for introducing students to J.M.W. Turner’s The Slave Ship.

When J.M.W. Turner first exhibited The Slave Ship, originally titled Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying—Typhon Coming On, he paired it with an excerpt from his unfinished poem Fallacies of Hope (1812).

Aloft all hands, strike the top-masts and belay;

Yon angry setting sun and fierce-edged clouds

Declare the Typhon’s coming.

Before it sweeps your decks, throw overboard

The dead and dying – ne’er heed their chains

Hope, Hope, fallacious Hope!

Where is thy market now?

This ekphrastic verse expands the meaning of the painting through the artist’s own words and launched a poetic tradition that has flourished over time. “Where is thy market now?” Is this Turner’s own haunting taunt to all slavers? Paired with his painting, does Turner hone and amplify his warning that the world will face divine retribution for their sins against humanity? Bear in mind that Turner and other abolitionists wanted to use the strategic exhibition of The Slave Ship (1840) during an anti-slavery conference to reenergize the abolitionist movement and spread British anti-slavery efforts across the globe.

The eminent art critic John Ruskin, the painting’s original owner, extended this ekphrastic tradition in his influential Modern Painter’s (1843). In this five-volume work Ruskin argues that the landscape artist of his time, with their ability to render atmospheric effects and natural forces, surpassed past masters. And the greatest of these, he contends, was J.M.W. Turner. In a chapter on the accurate depiction of water, Ruskin waxes poetic in his vivid description of The Slave Ship, the painting he deemed Turner’s best work.

But, I think, the noblest sea that Turner has ever painted, and, if so, the noblest certainly ever painted by man, is that of the Slave Ship, the chief Academy picture of the Exhibition of 1840. It is a sunset on the Atlantic after prolonged storm; but the storm is partially lulled, and the torn and streaming rain-clouds are moving in scarlet lines to lose themselves in the hollow of the night. The whole surface of sea included in the picture is divided into two ridges of enormous swell, not high, nor local, but a low, broad heaving of the whole ocean, like the lifting of its bosom by deep-drawn breath after the torture of the storm. Between these two ridges, the fire of the sunset falls along the trough of the sea, dyeing it with an awful but glorious light, the intense and lurid splendor which burns like gold and bathes like blood. Along this fiery path and valley, the tossing waves by which the swell of the sea is restlessly divided, lift themselves in dark, indefinite, fantastic forms, each casting a faint and ghastly shadow behind it along the illumined foam. They do not rise everywhere, but three or four together in wild groups, fitfully and furiously, as the under strength of the swell compels or permits them; leaving between them treacherous spaces of level and whirling water, now lighted with green and lamp-like fire, now flashing back the gold of the declining sun, now fearfully dyed from above with the indistinguishable images of the burning clouds, which fall upon them in flakes of crimson and scarlet, and give to the reckless waves the added motion of their own fiery flying. Purple and blue, the lurid shadows of the hollow breakers are cast upon the mist of the night, which gathers cold and low, advancing like the shadow of death upon the guilty ship* as it labors amidst the lightning of the sea, its thin masts written upon the sky in lines of blood, girded with condemnation in that fearful hue which signs the sky with horror, and mixes its flaming flood with the sunlight,—and cast far along the desolate heave of the sepulchral waves, incarnadines the multitudinous sea.

I believe, if I were reduced to rest Turner’s immortality upon any single work, I should choose this. Its daring conception—ideal in the highest sense of the word—is based on the purest truth, and wrought out with the concentrated knowledge of a life; its color is absolutely perfect, not one false or morbid hue in any part or line, and so modulated that every square inch of canvas is a perfect composition; its drawing as accurate as fearless; the ship buoyant, bending, and full of motion; its tones as true as they are wonderful; and the whole picture dedicated to the most sublime of subjects and impressions—(completing thus the perfect system of all truth, which we have shown to be formed by Turner’s works)—the power, majesty, and deathfulness of the open, deep, illimitable Sea.

*She is a slaver, throwing her slaves overboard. The near sea is encumbered with corpses.

— John Ruskin describing J.M.W. Turner’s The Slave Ship, the painting his father bought for him, in his Modern Painters Volume I (of V), pages 382–383.

While celebrated for its eloquence, this passage’s singular focus on Turner’s technique to the exclusion of the horrifying subject caused many to question Ruskin’s personal inclinations. Does this reflect his imperialistic leanings? Is he indifferent to the fate of the Africans? This focus, however, is in keeping with his intent of describing how Turner’s masterful rendering of the sublime rises above other artists. This passage is also in keeping with the ekphrastic writings of the times that tended toward the descriptive to address the lack of faithful reproductions that we take for granted today. Even with his focus on representational veracity, Ruskin’s careful word choice suggests his moral standing against the depravity of the slave trade—“the intense and lurid splendor which burns like gold and bathes like blood,” “advancing like the shadow of death upon the guilty ship,” and “its thin masts written upon the sky in lines of blood.”

The writer and poet David Dabydeen counters Ruskin’s focus on Turner’s seascape technique with Turner (1994), an epic ekphrastic poem that focuses on the drowning Africans in the foreground of Turner’s painting. Echoing slave narratives, Dabydeen constructs a biography for a discarded stillborn baby as a vehicle to interrogate colonialism, racism, and the depiction of Africans in Western historical narratives.

Turner

by David DabydeenStillborn from all the signs. First a woman sobs

Above the creak of timbers and the cleaving

Of the sea, sobs from the depths of true

Hurt and grief, as you will never hear

But from woman giving birth, belly

Blown and flapping loose and torn like sails,

Rough sailors’ hands jerking and tugging

At ropes of veins, to no avail. Blood vessels

Burst asunder, all below – deck are drowned.

Afterwards, Stillness, but for the murmuring

Of women. The ship, anchored in compassion

And for profit’s sake (what well-bred captain

Can resist the call of his helpless

Concubine, or the prospect of a natural

Increase in cargo?), sets sail again,

The part – sometimes with its mother,

Tossed overboard. Such was my bounty

Delivered so unexpectedly that at first

I could not believe this miracle of fate,

This longed-for gift of motherhood.

What was deemed mere food for sharks will become

My fable. I named it Turner— An excerpt from David Dabydeen’s Turner: New and Selected Poems, Peepal Tree Press Ltd. (September 1, 2002), pages 9–40.

The interrelationship between sex, violence, and colonialism in this opening stanza becomes a recurring theme as Dabydeen’s poem critiques the glorified narrative put forth by European historians and artists. To further implicate these cultural leaders, Dabydeen names the slave ship captain Turner (as well as the still born infant). In giving voice to one of the discarded Africans, Dabydeen underscores the importance of challenging the established order and adding alternative perspectives and histories.

The same year Dabydeen published “Turner,” William Patrick published another ekphrastic poem that drew on firsthand accounts from the Middle Passage. “Turner’s The Slave Ship” juxtaposes an adapted letter by Lt. John Matthews, a pro-slave trade lieutenant in the Royal Navy from the 1780s, with the thoughts of an art critic as he views Turner’s painting in the present-day Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Patrick uses expressive typography and writing conventions to underscore his narrators’ distinct personalities and ideological differences. The naval officer writes in clipped factual statements with conventional punctuation and tight regimented lines. The art critic’s fluid commentary in contrast flows across the page unfettered by punctuation, gesticulating with expressive line breaks and verbal flourishes. In addition to offering a Ruskin-like analysis of Turner’s technique, Patrick’s art critic also includes phrases and accounts from slave and abolitionist narratives.

Turner’s The Slave Ship

by William B. PatrickMy dear friend, I hope I am able, with this,

my last response, to finally lighten

your childish heart with a short analysis

of slaving, and to prove its necessity

for this hopeless continent of Africa.

What minor part of the Trade’s history

is known by me would please you far less

than what I have seen, myself, along the river

called Sierra Leone, and in this oppressive wilderness

that covers the coast. In my third year

of tropical life, what I have learned

of slavery shows our methods much less severe

than the natives’ own, and, in the end,

leaves them more fortunate than most comprehend.These upraised hands

and this one leg

upside down in the right foreground

the one exposed

mid-thigh to toe

as it slides down surrounded

by white fish

with bulging black eyes

and perfect hunger in their eager

upturned tails

these few

extremities

easily mistaken for fish

or waves

and caught

for this one instant

between the onrushing diagonal rain

and the torrential sea

that accepts

everyone

even this ship

on the left

with its blood-red empty masts

tipping back

these evanescent strokes are people

Already almost

completely under

the burnt umber and white-lead foam

flecked with hovering gulls

these bodies

you can’t see were chained sideways

ass to face alive or dead

this morning

in the slippery hold you also won’t see here

The blood

squeezed from their bodies

steamed up through

gratings

and became this swollen sky

that sweeps up here

to the left

upper corner

Before the first ominous red of morning

a small boy

who dreamed of the moon

over his empty village

woke up

crying

Kickeraboo kickeraboo

We are dying

We are dyingFrom what history I have collected, each war

provides the victorious tribe,

if they be cannibals, with much more

than can be preserved, or, if planting-time,

with field slaves. Most, if taken after harvest,

die. For almost any crime,

natives will sell a man, if they let him live.

If not made household or harem slaves,

before we Europeans came, these captured natives

could only hope to remain strong

each year when planting-time returned.

Believe me, slaves have been used here as long

as people have walked. Now, at least, as our boats

sail, the natives sell before they cut slaves’ throats.—An excerpt from William B. Patrick’s “Turner’s The Slave Ship” in The Southern Review; Summer 1994, pages 563–576. Or see Patrick’s book These Upraised Hands BOA Editions, Ltd., 1995, pages 51–63.

Dabydeen and Patrick both model how slave narratives and other historic documents can be used to create ekphrastic poems that imbue Turner’s The Slave Trade with added meaning and perspective. Now its time for students to extend this ekphrastic tradition.

The following free online readings offer firsthand accounts of the slave trade’s Middle Passage. Have students choose texts of most interest to them and share their new learning through class discussions. Note commonalities and differences across these accounts and carefully read for point of view. Then, the steps that follow will guide students in creating their own ekphrastic poems.

The Question Formulation Technique (QFT) can help turn art observations and wonderings into inquiry-based research questions that build on student insights and interests. For ideas on how to structure inquiry circles see Stefanie Harvey and Smokey Daniels Comprehension and Collaboration: Inquiry Circles for Curiosity, Engagement, and Understanding.

Text Sets

If you are short on time, these text sets can help students quickly access excerpts of slave narratives and testimony from slave ship crew.

- Excerpts from Slave Narratives edited by Steven Mintz from the University of Houston offers primary sources text sets that chronicle slavery from enslavement to emancipation. The Enslavement and Middle Passage readings are especially appropriate for this inquiry.

- Durham University’s 2007 exhibit Remembering Slavery, note especially the Middle Passage resource in “The Triangle Trade.”

- Documenting the American South (DocSouth), a digital publishing initiative sponsored by the University Library at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is an amazingly rich primary source database that chronicles Southern perspectives on American history and culture. The collection North American Slave Narratives and the superb search function helps access a wealth of resources.

Primary Source Books and Documents

If you like to read and research outside the lines these historic artifacts are for you. The following list highlights the most pertinent pages, but keep reading and mine the surrounding pages for all they have to offer. Have I mentioned how awesome the Internet is?

- The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African, by Olaudah Equiano, Chapter 2.

- The Blind African Slave, or Memoirs of Boyrereau Brinch, Nick-named Jeffrey Brace. With an Account of His Captivity, Sufferings, Sales, Travels, Emancipation,… Chapter IV, pages 87–93.

- The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture, The Negro Patriot of Hayti: Comprising an Account of the Struggle for Liberty in the Island, and a Sketch of Its History to the Present Period, Chapter 3, pages 16–18.

- Abridgement of the minutes of the evidence: Taken before a Committee of the Whole House, to whom it was referred to consider of the slave-trade, [1789-1791], pages 36–38. This whole book is a goldmine for research, but this testimony from Trotter (slave ship doctor on the Brookes) is especially harrowing.

- An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa by Alexander Falconbridge (slave ship doctor turned abolitionist), Chapter 3: “Treatment of Slaves” pages 19–32.

- “A Supplement to the Description of the Coasts of North and South Guinea” by James Barbot, Jr. (a sailor aboard the English slaver Don Carlos) in Collection of Voyages and Travels (London, 1732), Slavery, page 47, 270, Slave Revolt, page 513, The General Observations on Management of Slaves, pages 546–547.

- A voyage to the river Sierra-Leone, on the coast of Africa: Containing an account of the trade and productions of the country, and of the civil and religious customs and manners of the people; in a series of letters to a friend in England by John Matthews, lieutenant in the Royal Navy, (1788) See Letter VII, “The African Slave Trade” pages 137–159. (A source document for William B. Patrick’s “Turner’s The Slave Ship”)

- Liverpool And Slavery: An Historical Account of the Liverpool-African Slave Trade, (1884), Chapter VI, “Description of the Slave Ship ‘Brookes,’” pages 29–32 and Chapter VII, “The Ship ‘Thomas’ on her Voyage from Africa to Jamaica, with 630 Slaves,” pages 33–39.

Baron Montesquies affirmed “It is impossible to allow that the negroes are men; because, if we allow them to be men, it will begin to be believed that we ourselves are not Christians.”

Share your inquiry findings through found ekphrastic poems.

An ekphrastic poem is a vivid description of a work of art where the poet may amplify and expand its meaning. While early ekphrastic poems relied almost exclusively on detailed descriptions of the art, modern ekphrastic poems interpret, inhabit, confront, and speak to the art or artist. Found poetry mines everyday print material, such as newspapers, songs, and signs, for expressive words and phrases and then rearranges them into poem form. Turner’s Slave Ship provides the work of art to respond to. The slave narratives and testimony from slave ship crew offer the print materials to sample and riff on.

Don’t waste your time worrying about writing conventions and rules of grammar. Don’t tell a short story. That has been done. But, do collaborate with the authors who wrote the firsthand accounts above and, in an expressive manner, bring added meaning and perspective to Turner’s Slave Ship. Here are some steps to guide you through the process.

- Identify the passages you find most compelling.

- Reread the text and create a list of words and phrases (only a dozen or so, so you pick the best) that resonate with you or you find especially expressive.

- Color code your list to organize your words into categories. These categories should reflect relationships you notice and may include such categories as words about the senses (things heard or smelled or seen), words about emotions, words about memories.

- Consider other ways to sort and sift your words. For example, write individual words on sticky notes and rearrange them to find new relationships.

- Regroup your words into visual or auditory patterns and consider how the juxtaposition of words can create new meanings and can instill patterns and rhythms that engage the eye, the ear, and the mind.

- Translate these words and patterns into a single coherent poem that makes the reader see Turner’s Slave Ship in a new light or with greater clarity. Consider how your poem reads, sounds, and looks.

- Provide a concise biographical statement on the author(s) you collaborated with.

Learn more about ekphrastic poetry with a writing lesson on Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night.

Ekphrastic poetry is also explored in the lesson on Picasso’s mural Guernica.

Turner’s Seas

by Kathleen RaineWe call them beautiful,

Turner’s appalling seas, shipwreck and deluge

Where man’s contraptions, mast and hull,

Lurch, capsize, shatter to driftwood in the whelming surge and swell,

Men and women like spindrift hurled in spray

And no survivors in those sliding glassy graves.—An excerpt from Kathleen Raine’s “Turner’s Seas,” The Southern Review, Winter 1978, page 87. Listen to Raine’s recite her poem.

Raine’s, like Ruskin, offers a vivid and eloquent description of Turner’s sea scapes, but instead of focusing on Turner’s technique, she explores the humanity in the sublime.

Turner’s Slave Ship

by R. T. SmithThe colors rage, conflagration in an apothecary shop,

but this is mid-Atlantic, sunsmear warring with storm,

that purple scourge off the bow recalling Ruskin’s claim

—he owned the canvas once—it is the shadow of death

upon the guilty ship. Not God’s wrath, but Wrath

itself, the thing older than worship or remorse.

Much as he loved the craft of it all—three-masted

schooner (maybe Dutch), roil of great waters, brushwork

anguished, the colors in tormented cloud and shaft

and whorl—Ruskin could not keep it in his rooms.

“Terrible punishment, if just,” he wrote, “will not

keep silent when the candles are snuffed.” In chaos,

sky and sea are one, but distinct enough (starboard

foreground and center) just before a gray wave breaks,

arms upthrust from the molten swaths of lit pigment,

and about each wrist the linked shackles are visible,

thrashing, last grasp of the ailing thrown overboard

to claim insurance for “drownlings.” The supercargo,

no doubt, with his bills of lading scratched off

the names, which were only numbers, and noted

“Lost.” A travesty. Turner thought, struck by lines

from Thomson’s The Seasons and first-hand accounts

of the Zong massacre. He wanted to paint a sermon

wild with beauty and Hell’s horrors, all in the cause

of abolition. He wanted to halt the catastrophe,

so he called his work Slavers Throwing overboard

the Dead and Dying—Typhon coming on (1839).— The first of three stanzas from R. T. Smith’s “Turner’s Slave Ship,” Atlanta Review 20.2 (2014): pages 104–105.

Smith reflects on his experience with the painting in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. Because Smith’s poem melds the history and criticisms of Turner’s painting explored here, it is ideal as a summarizing reading. The Free Library by Fairfax offers the complete poem in a pdf format.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.