Teach close reading skills, satire, and mythmaking with Grant Wood’s Parson Weems’ Fable

Parson Weems’ Fable is in the collection of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. Visit their website for detailed information. Click on the painting for a high quality image that can be magnified. Learn about the painting’s backstory with an interactive game: Puzzled by Parson Weems’ Fable.

Parson Weems’ Fable is in the collection of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. Visit their website for detailed information. Click on the painting for a high quality image that can be magnified. Learn about the painting’s backstory with an interactive game: Puzzled by Parson Weems’ Fable.

The following anecdote is a case in point. It is too valuable to be lost, and too true to be doubted; for it was communicated to me by the same excellent lady to whom I am indebted for the last [story].

When George,” said she, “was about six years old, he was made the wealthy master of a hatchet! of which, like most little boys, he was immoderately fond, and was constantly going about chopping everything that came in his way. One day, in the garden, where he often amused himself hacking his mother’s pea-sticks, he unluckily tried the edge of his hatchet on the body of a beautiful young English cherry-tree, which he barked so terribly, that I don’t believe the tree ever got the better of it. The next morning the old gentleman, finding out what had befallen his tree, which, by the by, was a great favourite, came into the house; and with much warmth asked for the mischievous author, declaring at the same time, that he would not have taken five guineas for his tree. Nobody could tell him anything about it. Presently George and his hatchet made their appearance. “George,” said his father, “do you know who killed that beautiful little cherry tree yonder in the garden? ” This was a tough question; and George staggered under it for a moment; but quickly recovered himself: and looking at his father, with the sweet face of youth brightened with the inexpressible charm of all-conquering truth, he bravely cried out, “I can’t tell a lie, Pa; you know I can’t tell a lie. I did cut it with my hatchet.” “Run to my arms, you dearest boy,” cried his father in transports, “run to my arms; glad am I, George, that you killed my tree; for you have paid me for it a thousand fold. Such an act of heroism in my son is more worth than a thousand trees, though blossomed with silver, and their fruits of purest gold.

—M.L. “Parson” Weems, The Life of George Washington (1800, pages 15–16) the original cherry tree myth.

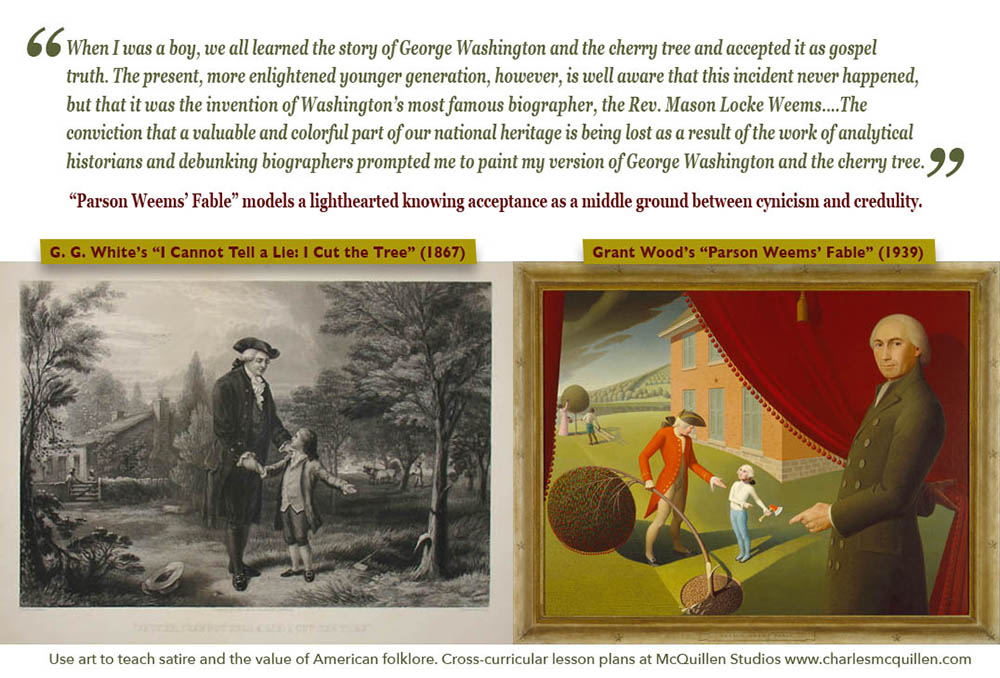

When I was a boy, we all learned the story of George Washington and the cherry tree and accepted it as gospel truth. The present, more enlightened younger generation, however, is well aware that this incident never happened, but that it was the invention of Washington’s most famous biographer, the Rev. Mason Locke Weems.…

The conviction that a valuable and colorful part of our national heritage is being lost as a result of the work of analytical historians and debunking biographers prompted me to paint my version of George Washington and the cherry tree. I sincerely hope that this painting will reawaken interest in the cherry tree and other bits of American folklore that are too good to lose. In our present unsettled times, when democracy is threatened on all sides, the preservation of our folklore is more important than generally realized…while our own patriotic mythology has been increasingly discredited and abandoned, the dictator nations have been building up their respective mythologies and have succeeded in making patriotism glamorous.

—Grant Wood explaining the need to fortifying American folklore and its underlying values to counter the social upheaval caused by the Great Depression and the rise of fascism in Europe.

Look at Parson Weems’ Fable. While it may not be as popular a classroom story today as it was a few generations ago, students may still have learned about Washington’s youthful indiscretion with a cherry tree. Begin by asking students the facts and myths they have learned about George Washington. Before reading the excerpt above, tell students the title of the piece and ask what is going on in this picture? This is a richly layered painting that draws on satire, an especially sophisticated form of humor. See how much students can decipher through a group discussion. Encourage students to identify the evidence that supports their reasoning. Students should likewise be encouraged to share wonderings and voice confusions. As the conversation slows, explain you are going to read two excerpts. The first is from Parson Weems’ The Life of George Washington (1800) a biography written less than a year after Washington’s death. The second excerpt is drawn from Grant Wood’s explanation on why he created this painting. After reading the excerpts ask how does this new insight change your understanding of the painting?

Grant Wood was born in 1891 on a farm near Anamosa, Iowa. And while he traveled throughout Europe to study art and learn from the grand masters, he returned home for his real inspiration. Wood was intensely proud of his rural upbringing and through his art he celebrated the human fabric of his community. His most famous painting, American Gothic offers a case in point. This backyard worldview was shared by others and eventually grew into an art movement called Regionalism. In his essay “Revolt Against the City,” Wood outlines Regionalism’s empowering principles and calls for artists to guard against the colonial dependency on European traditions he saw in the established art world.

The East is nearer to Europe in more than geographical position, and certain it is that the eyes of the seaport cities have long been focused upon the “mother” countries across the sea. But the colonial spirit is, of course, basically an imitative spirit, and we can have no hope of developing a culture of our own until that subserviency is put in its proper historical place.… The Great Depression has taught us many things, and not the least of them is self-reliance. It has thrown down the Tower of Babel erected in the years of a false prosperity; it has sent men and women back to the land; it has caused us to rediscover some of the old frontier virtues. In cutting us off from traditional but more artificial values, it has thrown us back upon certain true and fundamental things which are distinctively ours to use and exploit.

During the social upheaval of the Great Depression and the rise of fascism in Europe, Regionalism’s focus on grassroots imagery and local history offered Americans reassurance and fostered cultural pride. During this time of extremes, Wood pursued a course of intellectual moderation. In explaining the need for knowing acceptance as a middle ground between cynicism and credulity, Grant Wood describes how this sense of moderation guided him in painting Parson Weems’ Fable.

There are a number of stories…which I believe should be preserved in art if only for their color. It is, of course, good that we are wiser today and recognize historical fact from historical fiction. Still, when we began to ridicule the story of George and the cherry tree and quit teaching it to our children, something of color and imagination departed from American life. It is this something that I am interested in helping to preserve. As I see it, the most effective way to do this is frankly to accept these historical tales for what they are now known to be—folklore—and treat them in such a fashion that the realistic-minded, sophisticated people of our generation accept them.

In Parson Weems’ Fable Wood pulls back the curtain on an inspirational, though wholly fabricated story and invites the viewer to share in the inside joke. By affectionately debunking Washington’s cherry-tree legend, Wood’s painting celebrates America’s folklore and its underlying patriotic values, while lampooning its national mythology. He perpetuates patriotic virtues without being political or moralizing. He advances deep-held beliefs without being chauvinistic and dogmatic. Through his visual wit, Wood satirizes the self-righteous, debunkers and super-patriots alike, and he encourages Americans to take their values and traditions seriously, but not to take themselves too seriously.

Look like an art critic

Parson Weems’ Fable is in the collection of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. Visit their website to learn more. This image offers exquisite close-up detail.

Satire

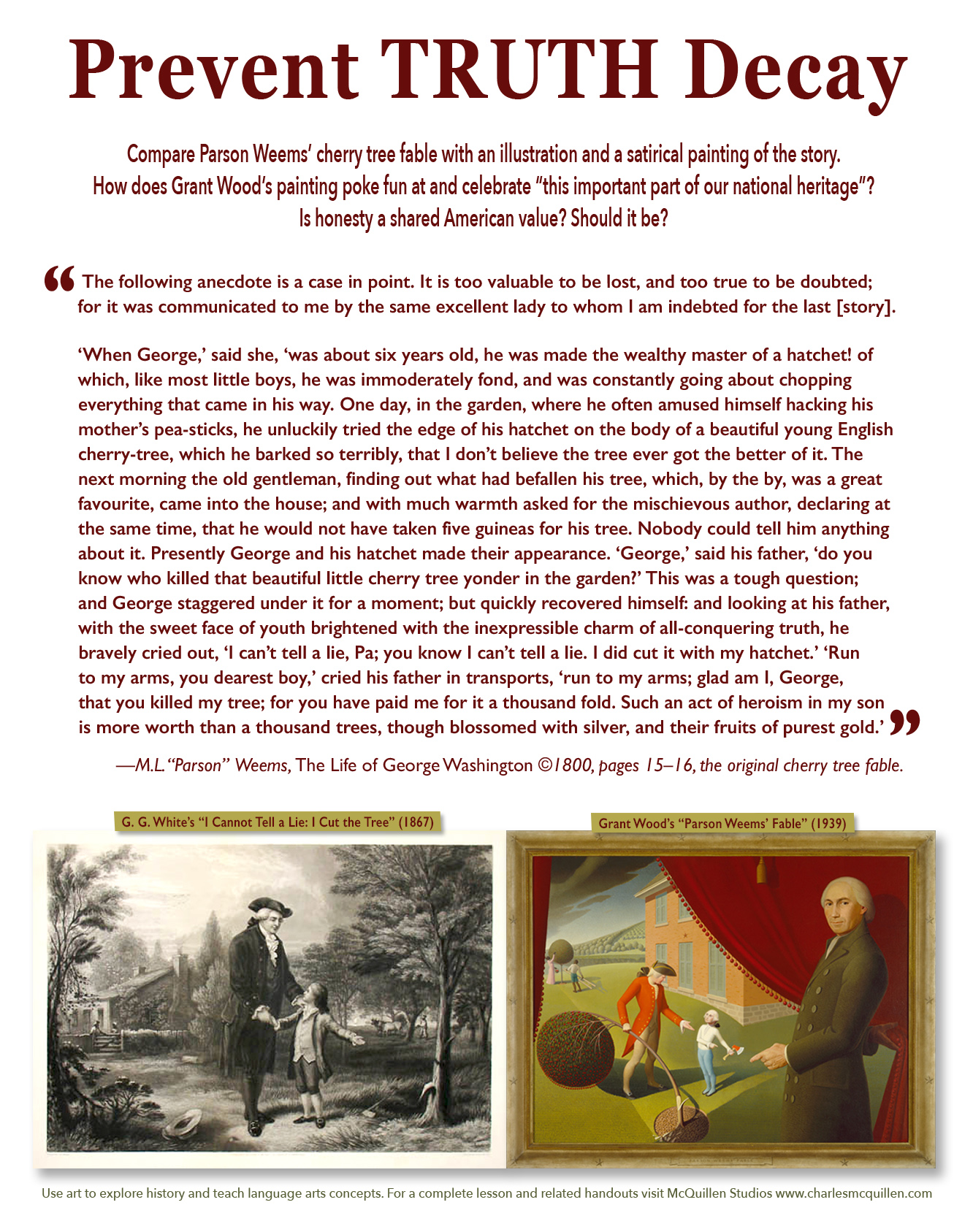

Point out and discuss: Satire uses humor to expose the absurdity of prevailing beliefs or actions with an eye to enacting some corrective measure. To appreciate Wood’s visual wit, compare his Parson Weems’ Fable with G.G. White’s more traditional depiction I Cannot Tell a Lie: I Cut the Tree. (1867) What do these images have in common and what humorous elements has Wood added? How does the satire in this painting serve Wood’s intentions?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: Both images show Washington’s father standing over him while gesturing toward to the barked cherry tree. And they both show Washington with the hatchet in close proximity. The background of both images shows slaves working on the plantation. One of the most humorous elements of the painting is George Washington’s adult head is placed on his six-year-old body. This makes George both instantly recognizable and freakishly absurd. Parson Weems’ wry smile while pointing at the scene also underscores Wood’s humorous intentions. The drawn back curtain that frames the landscape plays off C.W. Peale’s The Artist in His Museum and further enhances the drama and absurdity of the scene. Wood extends this absurdity by having the light source that illuminates the scene come from outside the left edge of the frame where the curtain has been lifted. This is the same light source that illuminates Weems and the curtain. Note how Wood uses the shadow from the frame to create a spotlight effect that focuses the viewer on the interaction between George and his father. He takes the visual joke further and further until you just have to laugh. While creating an opportunity to reflect on the value of truthfulness, Wood encourages the viewer to join in the inside joke and laugh at our own myth-making. The irony of depicting the falsehoods at the core of this legend on the importance of being truthful further adds to the humor.)

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: Both images show Washington’s father standing over him while gesturing toward to the barked cherry tree. And they both show Washington with the hatchet in close proximity. The background of both images shows slaves working on the plantation. One of the most humorous elements of the painting is George Washington’s adult head is placed on his six-year-old body. This makes George both instantly recognizable and freakishly absurd. Parson Weems’ wry smile while pointing at the scene also underscores Wood’s humorous intentions. The drawn back curtain that frames the landscape plays off C.W. Peale’s The Artist in His Museum and further enhances the drama and absurdity of the scene. Wood extends this absurdity by having the light source that illuminates the scene come from outside the left edge of the frame where the curtain has been lifted. This is the same light source that illuminates Weems and the curtain. Note how Wood uses the shadow from the frame to create a spotlight effect that focuses the viewer on the interaction between George and his father. He takes the visual joke further and further until you just have to laugh. While creating an opportunity to reflect on the value of truthfulness, Wood encourages the viewer to join in the inside joke and laugh at our own myth-making. The irony of depicting the falsehoods at the core of this legend on the importance of being truthful further adds to the humor.)

Perspective

Point out and discuss: Parson Weems’ Fable depicts perspective in three distinct ways. Have students identify the evidence from the painting as you describe how these techniques are used to create the illusion of space.

- Linear perspective shows objects decreasing in size the farther away they are from the viewer, eventually narrowing to a vanishing point on the horizon line. (Three comparable adults—Parson Weems, George Washington’s father, and the slave picking cherries—are rendered progressively smaller in size the farther they are from front edge of the picture frame. The comparable cherry trees are likewise shown progressively smaller. The trees on the distant hill diminish in size the farther up the hill they go. Note how even the short hard lines on the building narrow as the recede from the viewer.)

- Atmospheric perspective shows objects and the sky appearing hazier and less defined as they get farther away. (There is fine detail in Parson Weems’ pointing hand. The detail in the other hands in the painting diminish the farther the person gets from the viewer. The closest cherry tree exhibits a range of greens for the leaves and the cherries are distinct. The cherry tree in the background is less defined and its colors are less vibrant. The cherry trees in the orchard on the hill are even less vibrant and have almost no detail. The color of the sky fades from a rich blue in the foreground to a light hazy blue in the background.)

- “Bird’s-eye view” perspective places the viewer on a lofty perch above the scene. (The viewer looks eye to eye with Parson Weems but looks down on the scene of Washington and his father. Note how the viewer looks down into Washington’s upturned face as he talks to his father.)

How do these various ways of rendering perspective serve Wood’s intentions?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: The careful rendering of perspective in the painting makes the scene look realistic. The illusion of space is especially fitting since the cherry-tree legend had, for many years, the illusion of truth. The bird’s eye view of Washington has the viewer observing the scene from Weems’ perspective, which seems appropriate since he fabricated the myth. The detailed rendering of perspective and light is both hilarious and compelling. You know you are being tricked, but you marvel at the deftness of the illusion. This is how Wood feels about the cherry tree myth. Don’t just reject it because it is not authentic. Accept it for what it is and take away the joy and learning it provides.)

Repetition and Rhythm

Point out and discuss: The repetition of elements, such as color and shape, create visual rhythms within a painting, as well as add a sense of unity. How does Wood create repetition and rhythm in Parson Weems’ Fable? How do these visual rhythms serve Wood’s intentions?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: The shape and color of the curtain tassels are echoed in the cherries. The shape of the tassels and cherries are likewise echoed in the trees on the distant hill. The star decoration on the side of the house is picked up in the frame. The green of Weems’ coat can be found in the leaves of the cherry trees, the distant riverbank, and the forest beyond. The blue in the repeating shutters can also be found in the river, the distant sky, and George’s tights. The red in the father’s coat matches the red in the head of the hatchet. Red and green are complimentary colors and throughout this painting they are placed next to each other making the composition bright and dynamic. The visual rhythms created by repeating colors and geometric shapes bring a cohesive unity to a complex painting that depicts multiple planes of existence—the viewer’s world, Parson Weems’ world, and George Washington’s world. The stylized geometric shapes bring an artificial orderliness to an environment that is itself contrived.)

Think Like an Artist

George Washington was a cultural superstar like many of today’s athletes. Their public personas are used to promote certain values and encourage certain behaviors. Look at the advertising around a contemporary superstar? Do you think their public personas are real or fabricated? Make a list of the superstars you see in commercials, then in a few words describe the values they represent and how the media uses select images to construct their public personas. How would you explore this modern mythmaking and celebrate the associated value? If you were going to riff off of Grant Wood’s composition Parson Weems’ Fable, which elements would you keep and what elements would you replace?

Life Lesson

Embrace virtual Regionalism. It’s interesting to note that Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936), Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937), Frida Kahlo’s Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1939), and Grant Wood’s Parson Weem’s’ Fable (1939) were created within three years of each other and were influenced by many of the same world events. On their surface these works could not look more dissimilar. Yet, it can be argued, that all four of these artists share a regional sensibility. Picasso felt compelled to respond to the brutal attack on his homeland. Dorothea Lange found her artistic bearings when she documented the destitute people the Great Depression deposited in her neighborhood. Frida Kahlo found inspiration in her own personal suffering and indigenous art. And, Grant Wood found inspiration in his local traditions and folklore. In addition, none of these three artists succumbed to the imitative colonial dependency Wood described in his essay “Revolt Against the City.” Instead, they broke new ground when they built on the language, values, and traditions they grew up with. The Internet has made the world flatter than ever, and geography is no longer our master, but Regionalism still matters. There is a benefit for creative people to actively build their own communities and create environments with the people, ideas, and images they know intimately. And then they need to respond to, be inspired by, them.

Related Video

AVP Grant Wood (4:35) provides an overview of Grant Wood’s life and career up to the painting of American Gothic and then shows a few of the resulting parodies.

Grant Wood (1891-1942) by Dr. Christian Conrad (16:01) offers an art history lecture that steps through Wood’s art and his various influences.

Integrating into Your Curriculum

Artists oftentimes use common visual strategies or signposts to alert viewers to significant details in their art. Here are some ideas for using these visual signposts to unpack a work of art. Remember, the close reading skills in art appreciation are similar to the close reading practices taught in reading.

Click this link to teach about satire using Gran Wood’s Parson Weems’ Fable.

Literature Links: What piece of literature would you partner with Parson Weems’ Fable?

Parson Weem’s Fable could inform the study of myths and fables. It could also be used to study Regionalism.

- Grant Wood’s essay “Revolt Against the City” offers a unique opportunity to read about an artist’s ideas and guiding principles in his own words.

- Sinclair Lewis’s Main Street is a satirical novel that describes the lives of similar characters to the ones found in Wood’s paintings.

- Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer describes life in a small Missouri town in the late 1880s.

- Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird is a Southern Gothic novel written at about the same time Wood was painting his celebrated American Gothic.

- Willa Cather’s O Pioneers! describes farm life on the Great Plains at the turn of the 20th century.

- Garrison Keillor’s Lake Wobegon Days offers a contemporary view of Midwestern regionalism.

Writing Opportunity: Research writing could help students separate fact from fiction when it comes to George Washington. The game-based resource George Washington Fact or Fable? Tic-Tac-Toe can launch a writing unit.

- Did he really have wooden false teeth?

- Did George Washington have any children?

- Did he really throw a silver dollar across the Potomac River?

- Were his dogs named Sweet Lips and Madame Moose?

- Did George Washington really grow marijuana?

- Did Washington wear his hair in a ponytail?

- Was Washington deeply religious and did he pray on his knees at Valley Forge?

- What were Washington’s greatest virtues?

While Internet searches can help answer these and other questions the students can brainstorm, you may want students to begin their research at the official Mount Vernon website. The art-based inquiry study Analyze How Folklore and Historical Accounts Shape National Identity builds on this website.

The Question Formulation Technique (QFT) can help turn art observations and wonderings into inquiry-based research questions that build on student insights and interests. For ideas on how to structure inquiry circle see Stefanie Harvey and Smokey Daniels Comprehension and Collaboration: Inquiry Circles for Curiosity, Engagement, and Understanding.

How would you use this painting to build on one of your units of study? Please share if you have other ideas on how to teach Parson Weems’ Fable by Grant Wood as an English/language arts lesson plan.

Since Grant Wood was an art teacher this lesson closes with his quote on the value of an art education.

The aim of art education in the public schools is not to make more professional artists but to teach people to live happier, fuller lives; to extract more out of their experience, whatever that experience may be.”

Drag and Drop Handout JPGs

To make a handout drag and drop a jpg into a Word doc. In the Word doc open View and access the ruler. Adjust margins for optimum effect.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.