In Silent Suburb, 16 wooden birdhouses, with black circles painted where an entrance hole should be, are arranged in a 4’x4′ grid of new grass. This site-specific installation was developed for the “The Complex Harbor: Refuge, Protection, Threshold” show at the Art Complex Museum in Duxbury, MA.

The instructional flyer from the show

The American Lawn

America loves its lawns. The manicured lawn with its tightly cropped shrubs has become a poignant symbol of the suburban neighborhood. Mowing, watering, fertilizing, and raking have become weekly rituals across the United States as we strive to maintain the lush green grass that extends like a carpet from our homes.

Across the United States there are 58 million lawns covering more than 20 million acres. That makes grass the largest single “crop” in America and a significant part of the American landscape. Compound this fact with the following facts:

- Homeowners use up to 10 times more chemical pesticides per acre than farmers do.

- In 1984, more synthetic fertilizers were applied annually to American lawns than the entire country of India applied to all of its food crops.

- In 1990, 70 million pounds of herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides were applied to residential homes and gardens.

- In the eastern US lawn watering accounts for 30% of urban water use and in western US it accounts for as much as 60% of urban water use.

- Yard waste is the second-largest component of the solid waste stream that chokes our landfills.

- In the hour it takes to mow the average lawn, the inefficient two-cycle engine that powers the standards lawn mower emits pollutants equivalent to driving an automobile 350 miles.

So while your yard may seem ecologically insignificant, the cumulative effect of standard lawn-care practices clearly has environmental implications.

Closing Doors

The rampant destruction of ancient trees and the massive extinction of countless species have made the tropical rainforests the poster child of the environmental movement. But habitat destruction and species displacement are not unique to the tropics.

Across the United States the highly simplified lawn ecosystem has replaced the structurally complex ecosystems of woodlands, wetlands, grasslands and deserts. Diverse indigenous flora have been uprooted by manufactured turf grasses. Large native trees have been supplanted by ornamental shrubs. And as the homogeneous lawn displaces natural vegetation it also displaces the creatures that rely on the vegetation for cover, food, and shelter. First goes the wildflowers, then the insects, and then the songbirds. So while our green lawns may look environmentally friendly they may, in fact, be closing crucial ecological doors.

In as much as insensitive lawn care practices play a role in the continuing decline of local species of plants and animals, our backyards can also offer a very real opportunity to promote biotic diversity and preserve the indigenous flora and fauna that makes this region unique.

This widespread problem can only be solved one backyard at a time. We first need to stop thinking of our lawns as a grass carpet that is purchased by the foot. Rather, we need to remember that our backyards are small pieces of the biosphere and that every backyard can be a healthy, diverse ecosystem.

This is not to say that all aspects of our lawns are ecologically unsound or that we have to give up our treasured touch-football arenas and barbecue havens. Hardly, but we do need to reflect on the implications of our actions.

Envision a Pastoral Setting

One way of reducing the lawns impact on the local environment is as simple as relinquishing some control allowing nature to take its course. The shade-intolerant Kentucky bluegrass that has required excessive water and fertilizer will give way to native grasses better suited for sunless areas if such extra ordinary measures are withheld. Allowing grass clippings to decompose where they are cut provides a natural source of nutrients which saves on the expense of disposing of clippings and the cost of nitrogen fertilizer.

On a more proactive level, organic fertilizers and pesticides can be substituted for their chemical counterparts. By encouraging such native non-grass species as clover and low growing broad leaf plants your lawn can be both biologically diverse and green.

You might also consider how much lawn you actually need. Such non-lawn alternatives as plots of wildflowers become an oasis for songbirds and butterflies. Fruit-bearing shrubs offer both food and cover for a range of wildlife.

With a small investment, about as much as you would have spent on fertilizer and pesticides, you can purchase native trees and shrubs that will not only promote species diversity but will also serve such human needs as a snowfence, windbreak, or just provide privacy.

Unlike the uniform lawn ecosystem, there is no standard formula for designing a healthy backyard habitat. There are only a range of strategies from which to creatively draw. Through education and thoughtful planning we can adapt our lawns to fulfill our aesthetic, functional, and environmental needs.

Stewardship: A Call for All

“We stand now where two roads diverge. But unlike the roads in Robert Frost’s familiar poem, they are not equally fair. The road we have long been traveling is deceptively easy, a smooth superhighway on which we progress with great speed, but at its end lies disaster. The other fork of the road — the one less traveled by — offers our last, our only chance to reach a destination that assures the preservation of the earth.”

— Rachel Carson

Stewardship is the wise management and use of natural and agricultural resources. It is a principle that involves planning carefully and making informed decisions based on the land’s ability to support different uses. The basic principle of stewardship requires thoughtful decision making that balances the demands of today with the needs of tomorrow.

We need to explore a range of creative strategies that look for practical solutions beyond the status quo. By wisely choosing sound and ecologically responsible alternatives to the classic American lawn, we can unite our environmental concerns with direct personal action.

By collaborating with nature, our small section of the biosphere can reestablish an equilibrium that will evolve into a diverse pastoral landscape that will meet the needs of this generation and future generations.

“At first glance, the rows of bird houses outside the Art Complex Museum look like ordinary bird houses. A closer look, however, reveals that the circular openings are not openings at all, but painted black circles.

To Natick installation artist Charles S. McQuillen, his installation Silent Suburb is analogous to American suburban lawns—deceptive in their appearance. The reality, McQuillen said, is that the trend towards chemically-dependent simplified lawns interrupts ecosystems while maintaining what at face value appears to be environmentally sound.

The ‘subdivision of bird houses’ is one of 15 outdoor installations comprising the Art Complex Museum’s ‘The Complex Harbor: Refuge, Protection, Threshold’ on display through November 17.”

— Mahoney, Lesley. “In Through the Out Door: Art Complex Museum Features Outdoor Exhibit,”

Duxbury Mariner. May 21, 1998.

“For the first time since it launched major outdoor sculpture shows three years ago, the Art Complex Museum this year asked participating artists to create work related to a theme, and the result is ‘The Complex Harbor: Refuge, Protection, Threshold.’

Lisa Weber Greenberg, who co-curated the show with Laura Brown, said the harbor theme was chosen because of the museum’s seaside location, ‘but also,’ she wrote in the exhibition catalog’s foreword, ‘because of the numerous connections we saw between the role of a museum and that of a harbor. Both provide a place of refuge and protection, as well as a point of contact with outside influences.…

Other artists, such as Charles S. McQuillen of Natick, interpreted the theme in social and political terms. His sculpture comments on the negative effect that continued suburban sprawl is having on the natural environment. His Silent Suburb alludes to Rachel Carsons’s 1962 book Silent Spring. which spotlighted the ecological dangers of that era’s virtually indiscriminate use of pesticides and thereby helped to inspire the modern environmental movement.

The idea for Carson’s book is reputed to have taken root while the biologist was visiting friends in Duxbury and noticed fewer birds singing in their back yard than on earlier visits.

McQuillen’s work, a series of wood birdhouses mounted on steel fence posts, suggests that, like the widespread use of DDT in Carson’s time, the proliferation of manicured lawns and other trappings of suburbia are killing off the natural habitat. Like these manicured suburban lawns, his birdhouses, with doors shut, provide no refuge for wildlife.

‘Across the United States the highly simplified lawn ecosystem has replaced the structurally complex ecosystems of woodlands, wetlands, grasslands and deserts.’ He wrote in his artist’s statement. Manufactured turf grasses have uprooted diverse indigenous floras. Ornamental shrubs have supplanted native trees.…While our lawns may look environmentally friendly they may actually be closing crucial ecological doors.’”

— Montminy, Judith. “Harbor Theme Puts Sculptors on Common Ground,”

The Boston Globe South Weekly. Boston, MA. August, 1998.

“In Silent Suburb, Charles McQuillen builds a Levittown for birds, rows of identical birdhouses on stilts. Their sameness is depressing, and they have an edge of cruelty: Those round ‘doors’ are just painted on.”

— Temin, Christine. “Two Shows Play Hide-and-Seek With Viewers,”

The Boston Globe. Boston, MA. August 7, 1998

“Entitled ‘The Complex Harbor,’ the conceptual environmental art show is the third to be held on the grounds of the museum [Art Complex Museum in Duxbury] but the first to be unified by a single theme.…Indeed, the idea of harbor has been interpreted in a wide variety of ways by the 15 artists in the show.…Ultimately, for all these works, the site is the determining factor in a successful execution. Thus an artist must be able to recognize the right site when it presents itself.…Also concerned with man’s impact on the environment is Natick artist Charles S. McQuillen, whose grim, holeless birdhouses stand sentinel on a plot of freshly planted grass, sending the message that, ‘while our landscaped lawns may look environmentally friendly, they may actually be closing ecological doors.’”

— Gorfinkle, Constance. “Harboring Ideas: Duxbury Art Show Explores Themes of Coast and Havens,”

The Patriot Ledger. May 30, 1998.

The day before I showed up to install Silent Suburb a large metal sculpture had been removed from the front of the museum leaving a square bare patch in the lawn. Upon seeing it I couldn’t believe my good fortune and requested the site to assemble the piece. The new grass that grew in throughout the show enhanced this piece. Installation artists need to be inherently opportunistic—and a bit lucky.

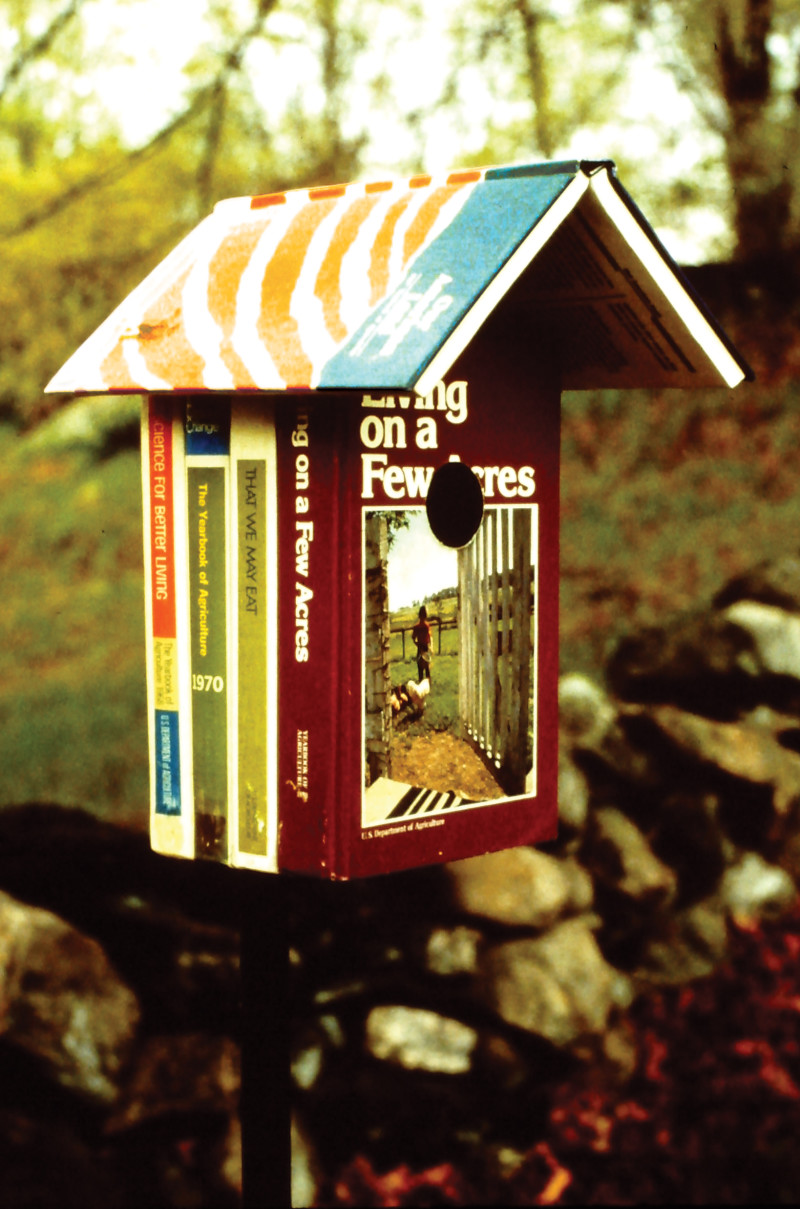

Being opportunistic also helped me with another aesthetic concern. As I designed prototype birdhouses for this installation I realized that to get the most impact from the fake painted openings I needed houses that looked authentic. Freshly painted birdhouses or birdhouses made of new wood looked suspiciously contrived. I wanted to create aged houses that looked from a distance to be real. Where could I find such aged wood? The wood from the freight pallet sculptures fit the bill perfectly.

A recurring question that I think about with many of my projects, but especially with this one is how much do I control the interpretation of the piece? How much should I telegraph my intentions? Maya Lin reminds us of an important concern every artist should consider when she said, “You have to let the viewers come away with their own conclusions. If you dictate what they should think, you’ve lost it.” I agree that for art to be memorable and lasting, it needs to be open for interpretation and personally meaningful for the viewer. There needs to be a level of trust and mutual respect between the artist and the viewer. The accompanying informational flyer expressed a clear message but since that was an incidental part of the installation does that keep this piece from being too didactic? Should we hold socially active art to a different standard than more conventional gallery art? This is something I ponder, and now so do you.

So this is my current view that allows me to continue to do this kind of work. The arts by their nature are acts of dialogue making and sharing and they only find their true fullness in the act of exchange. The artist and the audience create and interpret in relation to the other. Without the recognition of freedom, without the respect of the other, without the openness to personalize the aesthetic experience, art becomes propaganda. If the arts promote instead, possibility and dialogue, they can, as Maxine Greene contends, “establish a community of regard.” While this piece is more heavy-handed than most of my work, it is still trying to open a dialogue on an important topic. I’ll continue to try to sort this out. If you have insight you want to share, I am all ears.

- Analyze the pictures of the piece and the brief description. What is your initial response to what you see? Consider the theme of the show. How does the theme inform your interpretation of the piece?

- Read the reviews. Do the reviews shape your understanding of the piece?

- Read the copy from informational flyer. Does this shape your understanding of the piece? Do you think this statement influenced the way the critics responded to the piece?

- If time permits, pair this installation with a great long read (7000 words) on the history and costs of the American lawn. This excerpt from American Green: The Obsessive Quest for the Perfect Lawn, by Ted Steinberg is eye-opening and entertaining. Of course, the ultimate pairing is Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, the book that inspired this installation. That requires an especially dedicated read. Consider starting with a bite-size excerpt. The New Yorker originally published three excerpts from Carson’s book. These articles offer a glimpse of her genius.

- Silent Suburb offers an opportunity to explore the tensions that can exist in political or socially active art. Can art make abstract ideas and concerns visible and felt? Can political messaging make art too didactic and controlling?

See The Bluebird for another installation that uses birdhouse imagery. See Trespass for another installation that explores issues of species displacement and stewardship.

Examine other art works that use surprise and whimsy to engage the viewer

There are some artists who use games, humor, wit, or trickery to hook viewers and draw attention to environmental issues. Have students consider how these artists’ off-beat approach use compelling metaphors to engage viewers and explore issues in an accessible and memorable way; Vaughn Bell, Jackie Brookner, Tim Gaudreau, Fritz Haeg, Helen Lessick, Kathryn Miller, Christy Rupp, Steven Siegel, and Buster Simpson (don’t miss his early “River Rolaids”).