A series of site-specific installations drew inspiration from the social and historical significance of a place. Stacking wood from the closest tree to the next closest tree, to the next…was assembled in Charlotte, VT. Concave/Convex was crafted in a pecan grove in the Connemara Conservancy in north central Texas. The Temporary Installation of Sisyphus was designed for art sites around Boston, MA. Immobile Rolling Sculpture was created for an art show at the Larz Anderson Auto Museum in Brookline, MA.

Drawing on the social or historical significance of a site can give an installation a conceptual edge. The extra layers of meaning can make the piece more meaningful and memorable. For example, Concave/Convex was situated in a pecan grove, where the arching and interlocking limbs of the trees made the space feel like you were in a cathedral, especially when the dappled light shimmered through the leaves. (Yes, the photograph does not do justice to this.) This certainly enhanced the installation’s ritualistic qualities, but that would likely have been the case in many wood lots. That this site was on conservancy land, where they were actively protecting the open space from an encroaching housing development, imbued it with an added sense of the sacred.

Immobile Rolling Sculpture was likewise enhanced by the social significance of the site. Because the row of wheels are aligned to the grade of the hill, rather than along their axis, this piece can only “roll” in this exact spot. The absurdity of this takes on added significance when the piece was parked outside a museum dedicated to automobiles that no longer move.

Regrets, I have a few, and at least one to mention

The Temporary Installation of Sisyphus highlights an issue that I may have come full circle on. Oftentimes with conceptual art, conceiving the piece takes precedence over the execution of the piece, sometimes to the point where a piece never moves beyond an idea. Maybe The Temporary Installation of Sisyphus follows this thinking or maybe it was a cop out. You decide.

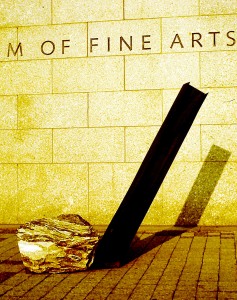

I have long felt that to be a successful sculptor you need to embrace, to some extent, the role of the existential hero. Sculpture as a genre is not the darling of the art world. As Barnett Newmann explains, “Sculpture is what you bump into when you back up to see a painting.” Sculptures are harder to document, transport, and store than most other artistic genres. ROI is usually questionable. Undaunted, successful sculptors press on like Sisyphus pushing their own individual boulders up a mountain. (Michelangelo might have been expressing his own existential leanings when he said, “A great sculpture can roll down a hill without breaking.” I am guessing he felt the same way about rolling up a mountain as well.)

When I conceived of this piece I wanted to play up this existential angle so I used a small boulder and an inclined I-beam that could be read as the slope of a mountain or a lever that Sisyphus might have used. In guerrilla fashion, I hurriedly rolled it up to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, set the stone with the I-beam, photographed it, and was on my way. (Hurriedly is a generous term here. The 500+ pound stone dangled like a pendulum on a rolling steel frame. There was nothing fast about moving it except when I hit the slightest downward slope.)

The logistical and liability concerns in doing this made me cower from extending the piece throughout Boston. Today, I wonder what I missed by not being more like Sisyphus and undertaking this task fully. What would I have learned and how would my thinking have evolved if I had made the effort to bring this installation to a broad range of outdoor sculptures around the city? How would this temporary installation have benefited from a visit to the Make Way for Ducklings statues in Boston’s Public Garden?

The installation artist Andy Goldsworthy said, “Ideas must be put to the test. That’s why we make things, otherwise they would be no more than ideas. There is often a huge difference between an idea and its realization. I’ve had what I thought were great ideas that just didn’t work.” I think it is also fitting to add that in testing, good ideas can become transformative ideas when a fully engaged artist responds to the conditions at hand. You’ll only know in the doing. This topic is explored further in an analysis of the Art Guys in the Teaching Opportunity below.

Teaching Opportunity

The Art Guys (Michael Galbreth and Jack Massing) are two conceptual artists who embrace the opportunity to test out their concepts to their fullest extent. They bring their art to the public with such good humor, energy, and personal commitment that “viewers” enjoy the opportunity to engage with their ideas. They establish a concept and then follow it to its logical conclusion, developing layers of understanding and insight along the way. While seemingly whimsical, their performances or “behavioral interventions” oftentimes explore serious issues and social mores.

As a way of introduction, watch these two TV news clips on The Art Guys.

- an interview on Houston PBS Art Insight (6:36)

- an interview with Bill Giest of CBS News Sunday Morning (7:09)

For a lesson that explores three select pieces by The Art Guy check out the Close Reading the Art of… post.