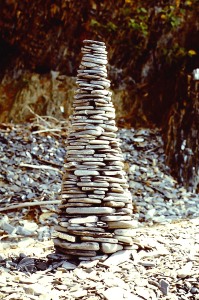

Stacking a Line installations use sand and stone cones to explore themes of toil and transience.

• High Tide to High Tide, starting at high tide use a traffic cone to form and place sand cones along the high tide line until the next high tide clears the beach, Crane Beach, MA.

• Stacking a Line from Sunrise to Sunset for Six Days, Shelburne Farms, VT.

A newspaper story about the installation

McQuillen brings innovative art to water’s edge

Charles McQuillen is a young sculptor who takes the common materials of nature and assembles them in ways that capture the imagination, spark new thoughts about everyday scenes, reframe the beach or field or woodland where he is working. And yet often his ‘constructions’ are gone in a few minutes or hours.

The piece he built last week could be longer lasting. It is built of stone. But its location on the edge of a beach near the Coach Barn at Shelburne Farms does place it at the mercy of the first strong southerly wind.

His work at Shelburne Farms is entitled “Stacking a Line from Sunrise to Sunset for Six Days.” The title and the structures he has built make many links to the place where he is working: the long days and six days of honest work of Vermont’s rural heritage, the stone walls that characterized farms in the state, the historic structure of Shelburne Farms itself, the distant mountains.

In six days Charles built a line of two-foot high stone cones or pylons demarking the line between the stony beach and the water of Lake Champlain. The orderly file of identical cones, meticulously crafted out of stones collected from the beach and assembled into sturdy ‘structures’ links the stony point curving out into the lake and the seawall along the road.

Charles says his goal was to draw out the highlights of the setting, the curves of the beach, the mountains in the distance, the line between land and water, the stony shore, and cast them in a different way to make people aware of them.

In other projects he has used the ‘found’ materials of his location to create interesting, though sometimes transitory, works:

• a huge snowball covered with handprints, created by sprinkling ashes over his hand on the snowball in a spatter painting technique, handprints which become a raised pattern as the sun melted the ashy portions

• a long line of cones built of sand at the tide line on Crane Beach in Massachusetts in a frantic 12 hour blitz, and then wiped out in 15 minutes as the tide reached them

• a sculpture park created on farmland in Texas in danger of being turned into a parking lot

• a tree trunk in the woods encircled with a pattern of handprints outlined with snow

“My projects help draw attention to a spot that needs to be noticed—like the endangered terns which nest on Crane Beach,” Charles said.

The week of hard at Shelburne Farms was a ‘vacation’ time for Charles who juggles an amazing schedule which includes working as an editor at a textbook company in Boston, working on a Masters of Fine Arts degree in sculpture at Boston Museum School through Tufts University evenings, and periodically heading off to create an environmental ‘construction,’ usually with a grant to support the project.

His “Sunrise to Sunset” piece is at Shelburne Farms ties in perfectly with the opening of the “Envisioned in a Pastoral Setting” exhibition and sale which opened last Friday night at the Coach Barn and continues through Monday, Oct 11. It embodies the natural and pastoral themes of the exhibition—and if the waves don’t wipe it out, will be visible for anyone approaching the Coach Barn for the exhibition.

Although the projects may be short-lived, Charles always documents the works on film, though he admits it is difficult to capture a three-dimensional piece in a two-dimensional medium. And often he has only a few minutes to catch the image before the wind, or sun, or waves have carried it away. “I take the photo and free myself from the piece,” he said.

Coming to Shelburne Farms for the project was a homecoming for Charles who grew up in Charlotte, graduated from CVU, and spent many hours at Shelburne Farms with his friends Chip Conquest and Dan Paxson who worked summers there. “When there was a rush to get the hay in, I helped out,” he said.

He graduated from College of the Holy Cross, and then took a Masters in education at UVM. He taught in an Eskimo village in Alaska where they taught him to carve and launched him into his current artistic arena.

The use of ‘found’ materials grew out of a need for free materials, the discovery that it was exciting to ‘play with the environment’ and the satisfaction he found from some early ‘guerrilla sculpture’ experiments in the woods near his home. “Art is so often laden with philosophy, instead of being fun,” he said.

— Graham, Rosalyn. “McQuillen brings innovative art to water’s edge,”

Shelburne News. Shelburne, VT. September 27, 1993.

I find the Stacking a Line installations especially satisfying in part because they unify many different trains of thought that preceded them. Like the early stone carvings they involve the same sense of physicality, toil, and responsiveness. Like the guerrilla installations they draw on the unique characteristics of the materials at hand. Like the time-specific sculptures they tap into natural cycles and celestial movements. And, like the site-specific sculptures, they celebrate the cultural and historic significance of a place.

And while these pieces build on many different explorations, they are most directly tied to Running Fence, the piece that uses the red poles on the beach—see the gallery of time-specific installations. In this piece I used 6-foot long closet poles as fence posts and the shadows they cast as the connecting wire. The idea was to place the first fence post, follow the shadow, and place the next fence post at the end of the shadow, with the other posts following in succession. When all the posts were used, the first post placed is moved up to the front, and so on. I proceeded to run from the front of the line to the to the back of the line to collect the next pole, thus it became a roving fence line. (You would be surprised how quickly the shadows shift.)

I liked the way this piece tapped into the human desire to partition and control the land and the inherent absurdity in establishing permanent boundaries in a constantly shifting landscape. About this time I came upon the work of Richard Long. This British sculptor used walks as his medium. He would establish parameters to a walk and then follow them to their logical conclusion with an array of spare, straightforward documentation. These worldwide wanderings struck me as especially British and it got me wondering about how an American might respond differently. We are a nation that celebrates the sentiment Robert Frost popularized, “Good fences make good neighbors.” And we have a rather intense love/hate relationship with the traffic cone. They are a ubiquitous image on our roadways and dictate our movements on a daily basis. He who controls the cones, controls the mob (see New Jersey Governor Chris Christie for a case in point). These ideas percolated together to inform the Stacking a Line installations.

- Analyze the pictures of the piece and the brief description. What is your initial response to what you see? How does the title help you understand the piece better?

- Read the newspaper account. Does this story shape your understanding of the piece?

- Explore the links to these two sites—Crane Beach and Shelburne Farms. Are these fitting sites for such installations? Why or why not?

- What are the benefits and challenges of creating temporal, site-specific installations from the materials at hand?

Are the artistic seeds for these installation found in any of the guerrilla installations or other site-specific installations? Which ones? Do these installations lay the groundwork for the rubberstamp installations? How so?

Compare and contrast different environmental installations

In guerrilla installations I highlighted a group of land artists. There is another group of artists who sculpt the earth with a very different sensibility. Check out these artists and their site-specific environmental installations; Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer, James Turrell, Alan Sonfist, David Nash, and Maya Lin.

Then consider these conceptual “walking” artists, Richard Long and Hamish Fulton, who also use the earth’s surface as their medium.

Have students compare and contrast the land artists with these groups of artists. Their tools, their touch, the scale in which they work, their audience, their conceptual motivations, and their aesthetic ideals reflect very different views of the world and ways of working in the environment.