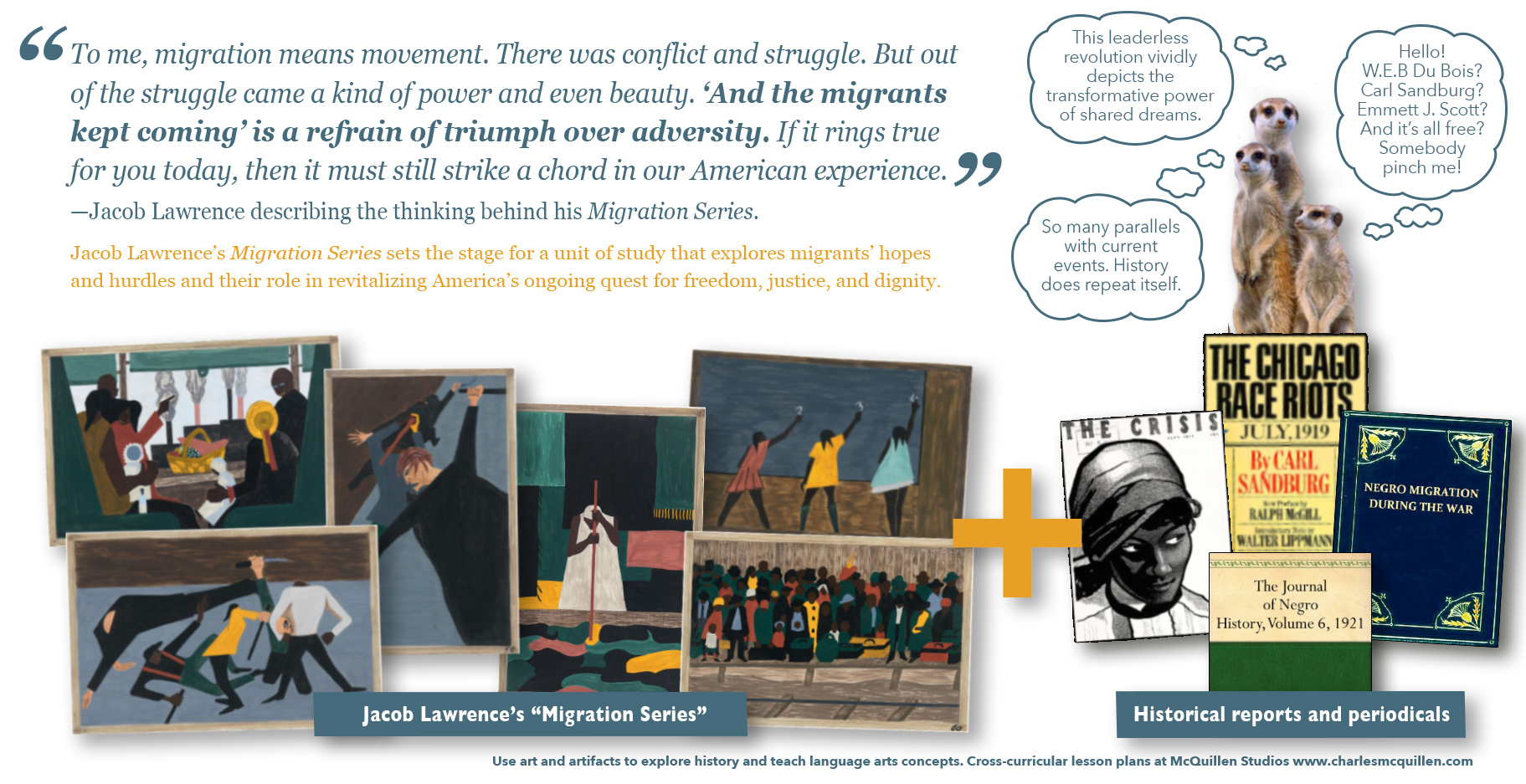

Teach close reading skills, symbolism, and the Great Migration with Jacob Lawrence’s The Migration Series

Jacob Lawrence’s 60 panel The Migration Series is shared between the Museum of Modern Art, New York City and the Phillips Collection, Washington, DC. See their websites for detailed information and larger, high quality images.

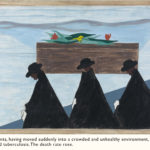

This is the story of an exodus of African-Americans who left their homes and farms in the South around the time of World War I and traveled to northern industrial cities in search of better lives. It was a momentous journey. Their movement resulted in one of the biggest population shifts in the history of the United States, and the migration is still going on for many people today.…

To me, migration means movement. While I was painting, I thought about trains and people walking to the stations. I thought about the field hands leaving their farms to become factory workers, and about the families that sometimes got left behind. The choices made were hard ones, so I wanted to show what made the people get on those northbound trains. I also wanted to show just what is cost to ride them. Uprooting yourself from one way of life to make your way to another involves conflict and struggle. But out of the struggle comes a kind of power, and even beauty. I tried to convey this in the rhythm of the pictures, and in the repetition of certain images.

‘And the migrants kept coming,’ is a refrain of triumph over adversity. My family and others left the South on a quest for freedom, justice, and dignity. If our story rings true for you today, then it must still strike a chord in our American experience.

—Jacob Lawrence describing the thinking behind his The Migration Series in the forward of his book The Great Migration: An American Story (1991)

I don’t think about this series in terms of history. I think in terms of contemporary life. It was such a part of me I didn’t think of something outside.…It was a portrait of myself, a portrait of my family, a portrait of my peers.…It was like a still life with bread, a still life with flowers. It was like a landscape you see.

—Jacob Lawrence from the Phillips Collection catalog Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series (1993)

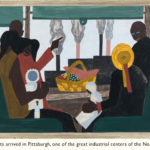

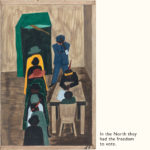

Look at panels 45–60 of The Migration Series (click on the gallery to enlarge images). Before reading the excerpts above, tell students the title of the series and that you will read the captions that accompany each image. Lawrence carefully crafted these captions so it is important honor his intentions and keep the text and images together.

Ask what is going on in these paintings? Between the paintings and descriptive captions there is a lot to process. Encourage students to discuss the series as a whole and to identify individual images that are especially meaningful to them. Also, encourage students to identify the evidence that supports the reasoning behind their interpretations. Students should likewise share wonderings and voice confusions. As the conversation slows, explain you are going to read two Lawrence quotes about his thoughts and motivations in creating this series. After reading the excerpts ask how does this new insight change your understanding of the paintings?

Begin with art history

Jacob Lawrence was born in Atlantic City, New Jersey in 1917 to a cook and a domestic worker who had migrated from the South. After his parents divorced, the family relocated to Philadelphia. For three years Jacob and his two younger siblings lived in foster care while his mother looked for work in New York City. At the age of 13 Jacob was reunited with his mother in Harlem. Lawrence’s mother enrolled him in after-school arts and craft classes. Even after dropping out of school at the age of 16 to work in a laundromat and a printing plant, Lawrence continued his artistic studies at the Harlem Art Workshop.

Influential art teachers recognized Lawrence’s talents early on and helped him secure scholarships and paid positions, including a job in the WPA’s easel division. By his 20s Lawrence developed his own unique approach to art. Some of his best-known early works were biographical series that celebrated the exploits of famous leaders who fought for liberty including the Haitian general Toussaint L’Ouverture and the abolitionists Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and John Brown. He also developed a style of art he called “dynamic cubism” that used bold flat colors and jagged compositions to create dramatic social realist paintings.

Lawrence was 23 when he applied for and received a fellowship from the Julius Rosenwald Fund. This bought him time and space to create his Migration Series, 60 paintings that chronicle the massive migration of 1.6 million African Americans from rural communities in the South to cities in the North. As Lawrence later explained,

This is the story of an exodus of African-Americans who left their homes and farms in the South around the time of World War I and traveled to northern industrial cities in search of better lives. It was a momentous journey. Their movement resulted in one of the biggest population shifts in the history of the United States, and the migration is still going on for many people today.

Building on the stories and aesthetics of his Harlem community and six months of research, writing, and sketching in a branch of the New York Public Library, Lawrence found a studio that allowed him to work on all 60 panels at once. To maintain coherence across the series, Lawrence used unmixed tempera paints, starting with the dark colors and moving on to the lighter colors. Sentence-long captions for each of the 60 paintings reinforced the narrative. The series brought Lawrence national recognition when the series was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art and 26 of the panels received a lavish layout in Fortune magazine.

Throughout his long distinguished career Jacob Lawrence used bright clear crisp colors and dramatic gestures to depict contemporary scenes and common people making history.

Look like an art critic

Jacob Lawrence’s 60 panel The Migration Series is shared between the Museum of Modern Art, New York City and the Phillips Collection, Washington, DC. MoMA has the even numbered panels and the Phillips Collection has the odd numbered panels. The Phillips Collection website supplements its collection with letters from migrant, historical photographs, related artwork. MoMA’s One-Way Ticket: Jacob Lawrence’s Migration site supplements its collection with poems and musical audio clips, historical artifacts, and news accounts. If you have time to view the entire series, both sites will support your instructional needs. Thank you Phillips Collection and MoMA!

Creating coherence and rhythm

Point out and discuss: Lawrence saw the Migration Series as a single work of art. (He requested that the entire series be sold together even though that made its purchase more difficult and less lucrative.) He employed a number of artistic elements that unified the series. He was also careful to infuse a sense of motion that complimented the migration theme. Look across the panels provided here or at the entire series. How does Lawrence create a sense of unity across the panels and instill a sense of motion?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: Lawrence used the same limited palette of unmixed colors to unify the panels. These colors also create a rhythm. For example, look how the same bright yellow creates a highlight that dances across the canvasses. Look how the use of dense black and browns create a consistent background to the to the images. The short sentences and certain repeating words create an auditory rhythm that echoes the visual rhythm created by the dabs of color. The shifting format of the panels from horizontal/landscape to vertical/portrait and back again create a staccato rhythm across the series. Repeating shapes and dynamic gestures instill a sense of pulsing motion. Strong diagonal and horizontal lines that shoot beyond the panels’ frames likewise link the compositions and keep the viewer’s eyes looking ahead. Fluctuating perspectives from close up to far away and from high to low likewise add a sense of movement across the series.)

Reading symbols

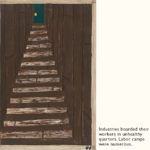

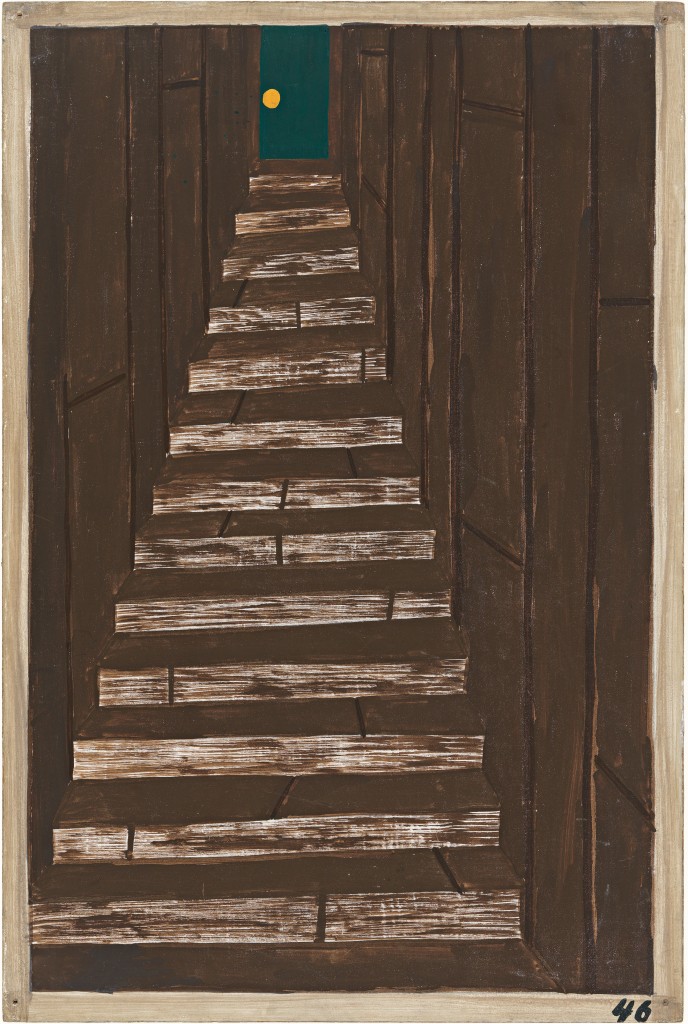

Point out and discuss: Throughout his Migration Series Lawrence uses symbols to tell the story of the Great Migration. Some of the symbols directly illustrate their accompanying captions. Other symbols are more metaphorical. Consider panel 46. The image of a narrow staircase is accompanied by the caption “Industries attempted to board their labor in quarters that were oftentimes very unhealthy. Labor camps were numerous.” How can the image of the staircase be read as a symbol of the Great Migration and the challenges blacks faced in relocating to the North?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: Like the caption, the painting of the stairs can have a foreboding interpretation. The stairway is dark, narrow, and steep. They are not elegant like a marble staircase. They do not have a banister that suggests safety and easy accessibility. These stairs require steady perseverance, a long slow progression to ascend. The stairs emphasize the unknown that the migrants faced as they left their rural communities for cities in the North. Is that a closed green door at the top of the stairs or is that yellow doorknob really the moon in the night sky? Like mounting these stairs to the unknown, it took a leap of faith to move north. Because the stairs ascend there is a sense of hope that they will take you to a higher level, that they represent progress built on prior experience. The starkness of the stairs makes them seem ladder-like, with each tread appearing like a rung. That the doorknob could be the moon instills a spiritual connection to the heavens. There are 13 steps, a good omen in art history since the foot that began the climb also is the first to the top—as a longtime museum goer and a student of Renaissance Italian art, Lawrence would appreciate the significance of odd-number steps. These stairs evoke the uncertainty, challenges, and hope within the Great Migration.)

NOTE: If students are intrigued by the stairs symbolism consider adding to the discussion an analysis of the related poem Mother to Son by Langston Hughes.

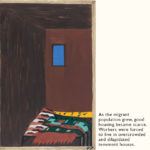

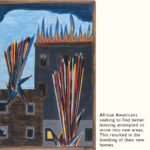

Compare Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series paintings with Ben Shahn’s illustrations for the Hickman Story

Point out and discuss: Click on the gallery to enlarge images. In 1948, the artist Ben Shahn was asked to illustrate a Harper’s magazine article that examined a tragic fire that killed four siblings—Leslie (14), Elvena (9), Sylvester (7), and Velvena (4) Hickman. Like the families Lawrence depicted, the Hickmans were a black family from the South who migrated north seeking a better life. And, as Lawrence also depicted, the Hickman fire resulted from housing segregation, squalid conditions, and possibly intentional violence. The children’s father, James Hickman, became increasingly distraught when the landlord, who had previously threatened to burn the building to displace the tenants for renters who would pay more, appeared to get away with the crime. Seven months after the fire, overcome with grief and with a gun in hand, Hickman confronted, and eventually killed, the unrepentant landlord, David Coleman. The magazine article described the factors that caused the Hickmans to migrate, the discriminatory housing practices that lead to the fire, and James Hickman’s murder trial. Compare Shahn’s illustrations with Lawrence’s paintings. How are the stories these artists tell similar? How do Shahn and Lawrence offer different perspectives of the Great Migration and what are the merits of these different perspectives?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers to how the stories are similar: Both artists focused on the aspirations and struggles of common people. Both artists use simple shapes and lines to tell a story. Both artists focus on people who moved from the rural South to the industrial North as part of the Great Migration. Both artists highlight educational opportunities and a better quality of life as motivating factors in moving north. Both artists highlight the housing issues, desperation, and violence the migrants faced. Both artists highlight a love of family and a sense of spirituality as guiding forces. Both artists use text to reinforce and extend their art with descriptive captions.

How they offer different perspectives: While Shahn’s illustrations tell a story, the article that accompanies it provides necessary context. Lawrence’s paintings, on the other hand, stand alone as a work of art. By providing an expansive overview of an epic population shift, Lawrence’s painting chronicles historic trends and events. By providing an intimate portrait of a family’s experiences, Shahn’s approach puts a human face to historic events.)

Think Like an Artist

Create a Twitter-Worthy History. Lawrence’s art making process for his early series followed a similar methodical process. First he started by researching inspirational leaders and historic events. Research findings turned into draft captions and preparatory sketches that are further refined until they are organized into a series of carefully crafted panels. Throughout the process details are pared down to the essentials. Try the process for yourself. Chronicle an inspirational historic event or leader. Consider national, local, or personal histories of special significance to you. The challenge: limit your imagery to only 6 panels and limit your captions to a twitter-worthy 280 characters.

Life Lesson

Play with constraint. As a writer, what stirs your creative juices more an endless list of topics or the challenge of a six-word memoir? Leonardo da Vinci said “Art lives from constraints and dies from freedom.” Orson Welles echoed this sentiment some 450 years later when he said, “The enemy of art is the absence of limitations.” Some constraints can inspire creative responses. Lawrence’s Migration Series offers a case in point. When Lawrence was hired to be a W.P.A. artist in the late 1930s, he was deemed too young to manage one of the mural projects for which they were best known. Instead, he was assigned to the easel division. While inspired by the Mexican muralists (also note Picasso’s mural Guernica was likewise stealing headlines at this time), Lawrence created within the constraints of a standardized 18”x12”canvas. To unify the 60 panels into a single coherent piece, he also constrained his palette to a few unmixed colors. But constraints in scale and color did not diminish his efforts to depict an epic historic event or the reach of his work. To the contrary, his format lent itself to reproduction and publication and the general public have had a more direct experience of his work than many of the works of the most celebrated muralists. As you approach your own work, play with, don’t avoid, the constraints you face. To learn more about the relationship between constraint and creativity consider Patricia Stokes Creativity from Constraint: The Psychology of Breakthrough.

Related Videos and Lectures

- Jacob Lawrence and the Making of the Migration Series (18:58) This must-see documentary melds artist interviews, historical footage and artifacts, and curator analysis.

- Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series (11:24) Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris’ Smarthistory video offers a introductory overview of the entire series and highlights select images. NOTE: They read Lawrence’s original captions that were revised in 1993. The lesson above uses the revised captions.

- People on the Move: Beauty and Struggle in Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series (3:17) This Phillips Collection video offers a concise historical context for the series.

- Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series and the Legacy of Jim Crow/MoMA Live (1:37:31) While longer and more sophisticated than many classrooms can use, this lecture by three social justice activists creates a powerful context for viewing the series against historical artifacts and current racial discrimination.

Integrating into Your Curriculum

Artists oftentimes use common visual strategies or signposts to alert viewers to significant details in their art. Here are some ideas for using these visual signposts to unpack a work of art. Remember, the close reading skills in art appreciation are similar to the close reading practices taught in reading.

Literature Links: What piece of literature would you partner with Jacob Lawrence’s The Migration Series? The Migration Series offers a number of avenues for literary exploration.

African American Heroes and History: Early in his career Jacob Lawrence painted a number of series that chronicled the escapades of people who fought for rights of the oppressed—Toussaint L’Ouverture, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and John Brown. Some of these series have since been turned into sophisticated picture books worthy of analysis at many learning levels.

- Toussaint L’Ouverture: The Fight for Haiti’s Freedom (1996)

- Harriet Tubman: Harriet and the Promised Land (1993)

- John Brown: One Man Against Slavery (1993)

Ekphrastic Poetry Jacob Lawrence was inspired by poets and likewise inspired poets. The Museum of Modern Art’s Migration Series Poetry Suite offers a great opportunity to explore ekphrastic poetry. The Museum of Modern Art commissioned ten contemporary poets to write new poems in response to Jacob Lawrence’s The Migration Series. The MoMA site provides the poem and a reading by the poet. Have I mentioned how awesome the Internet is? If that is not enough YouTube offers a group poetry reading. In her forward to the suite, poet and essayist Elizabeth Alexander writes,

We can be fooled by the historical and serial aspects of Lawrence’s work, neglecting to see how it is also open-ended, inventive, allusive, fascinatingly strange. What happens when we look at the paintings one by one and unlace them from their context? What happens when a poet writes between the frames?

- “The Great Migration” by Yusef Komunyakaa

- “Year after Year We Visited Alabama” by Crystal Williams

- “Double Helix” by Crystal Williams

- “Migration Portraiture” by Nikky Finney

- “Another Great Ravager of the Crops Was the Boll Weevil” by Terrance Hayes

- “Four Premonitions of Migration” by Terrance Hayes

- “Migration” by Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon

- “Another man done…” by Tyehimba Jess

- “Negro Migration” by Tyehimba Jess

- “Say Grace” by Rita Dove

- “Protocol” by Rita Dove

- “As the Crow Flies” by Natasha Trethewey

- “Lave” by Patricia Spears Jones

- “Thataway” by Kevin Young

Literary Peers Lawrence intellectually, and frequently personally, interacted with a range of writers. These literary peers share Lawrence’s interests and themes.

- Langston Hughes’ poetry is often associated with the Great Migration especially One-Way Ticket (1948), Black Seed (1930), Mother to Son (1922 ), and PO’ Boy Blues (1926).

- Sterling Brown’s poem Strong Men (1931) describes the ongoing struggle forward in the face of racial oppression.

- Richard Wright’s Native Son (1940) explores the aftermath of the great migration in Chicago’s South Side through the experiences of Bigger Thomas.

- Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952) examines the social and intellectual issues facing African-Americans early in the twentieth century. Flying Home and Other Stories is a collection of short stories (see especially “Boy on a Train” (1998) that chronicle the experiences of different people swept up in the great migration.

- William Attaway’s Blood on the Forge (1941) offers a harrowing portrait of three African American brothers who migrate from Kentucky to work in Pennsylvania’s steel mills.

- Rudolph Fisher’s novels and short stories depict life and events during the Harlem Renaissance.

- Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration is the award-winning history that captures the voices and experiences of the Great Migration.

- John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath (1939) explores another great migration that transformed America.

- Sanora Babb’s Whose Names are Unknown (2004) chronicles the exploitation of Dust Bowl migrants.

Writing Opportunity: Inquiry-based research and writing

Jacob Lawrence chronicles the hopes and hurdles that shaped the Great Migration. At a basic level, these are the same hopes and hurdles migrants face today. Use Lawrence’s The Great Migration and firsthand accounts from the mainstream and black press to explore these dynamic push-pull forces and have students consider how they would respond to them then and now.

These articles are organized around the Great Migration’s causes and conflicts. Have students explore themes of their choice and share their new learning through class presentations. As historical artifacts, these articles also offer students opportunities to read for point of view. Have students note how the white and black media report the same events.

The Question Formulation Technique (QFT) can help turn art observations and wonderings into inquiry-based research questions that build on student insights and interests. For ideas on how to structure inquiry circle see Stefanie Harvey and Smokey Daniels Comprehension and Collaboration: Inquiry Circles for Curiosity, Engagement, and Understanding.

General Information and Archives

- The Negro Migration During the War, by Emmett J. Scott, 1919. Project Gutenberg is awesome. This history gives you insight into a resource that Jacob Lawrence drew heavily on for his research, though Lawrence gives a more positive spin to Scott’s topics. Note: The readability level of this resource is higher than the other resources below.

- The Chicago Race Riots, July, 1919 by Carl Sandburg. These are reprinted articles from the Chicago Daily News. Addressing many of the topics Lawrence depicts, these firsthand accounts can be used as a shared text to explore the causes and conflicts around the Great Migration. While well intentioned, Sandburg’s account has been criticized for being paternalistic and racially shortsighted so it may be beneficial to supplement with articles from the black media. (And yes, this is the same Carl Sandburg who won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for Cornhuskers that same year. He went on to win two more Pulitzers. What a show off.)

- “The Negro Migration of 1916–1918,” by Henderson H. Donald, Journal of Negro History 6, no 4 October 1921. This scholarly essay offers an analytical survey of the dynamic push-pull factors that drove the Great Migration. Further proof that Project Gutenberg is awesome. Check out this archive.

- “The Success of Negro Migration,” by Walter F. White, The Crisis, January 1929 (Vol. 19 No. 3), pages 112–115. This article offers a firsthand account of the great migration from the perspective of the NAACP. This archive affords hours of valuable sifting, the heart of any research.

- Visualize the Great Migration uses U.S. Census Data and infographics to describe and quantify the migration.

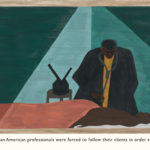

Employment Opportunities (Panels 2, 4, 17, 28, 29, 37, 38, 45, 50, 56, 57, 60)

- “Causes of the Migration,” Chapter III from The Negro Migration During the War by Emmett J. Scott. This chapter reads like a companion to Lawrence’s series and offers poignant firsthand accounts on the push-pull factors that drove the migration. If you need one concise chapter for shared reading and research this may meet your needs. Wow!

- “Additional Letters of Negro Migrants of 1916–1918: Letters Stating that Wages Received are not Satisfactory,” Journal of Negro History 4, no 4 October 1919. 60 letters to the Chicago Defender seeking employment express the troubles the migrants are leaving behind and their hopes in moving north.

- Seven letters to the Chicago Defender—a black newspaper published in Chicago that strongly urged southern blacks to migrate to the North—attest to migrants’ strong desire to “better their condition,” often risking their lives and possessions to make the trip north.

- “After Each Lynching,” Chapter 7 in The Chicago Race Riots, July, 1919 by Carl Sandburg describes how letters to the Chicago Defender highlight the push-pull forces that drove the Great Migration.

- “Demand for Negro Labor,” Chapter 5 in The Chicago Race Riots, July, 1919 by Carl Sandburg describes how dramatic post-World War I population shifts back to Europe and a burgeoning economy in northern cities created a demand for labor from the South.

- “New Industrial Opportunities,” Chapter 6 in The Chicago Race Riots, July, 1919 by Carl Sandburg provides an overview of the kinds of jobs and training that opened to black labor.

- “The Colored Woman in Industry” by Mary E. Jackson, The Crisis, May 1918 (Vol. 17 No. 1, pgs 12–17) describes the different opportunities and wages African American women received as they filled the industrial jobs vacated as soldiers left the work force for World War I.

- “Trades for Colored Women,” Chapter 8 in The Chicago Race Riots, July, 1919 by Carl Sandburg includes a clear recitation of employment facts as well as a letter between sisters that personalizes the statistics.

- “Unions and the Color Line,” Chapter 10 in The Chicago Race Riots, July, 1919 by Carl Sandburg explores the role organized labor played in addressing racial discrimination.

Race Riots (Panels 50 and 52)

The firsthand accounts of the race riots Lawrence depicts in panels 50–52, especially the East St, Louis race riot he specifically references, are ugly and may not be suitable for general classroom use. This fitting disclaimer accompanies the articles from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “The accounts hold back nothing in terms of graphic detail and gore. Even today, this reporting must run with a disclaimer cautioning readers to the violence contained herein. So too, must readers be warned of ugly racial terminology of the era, including the use of a racial epithet.”

Even with this brutality, the role big business, organized labor, politicians, the police, and the military played in inflaming the mob violence and racial discord should not go ignored. This history has many lessons for modern times. Consider more sanitized retellings. The Time’s History website describes the East St. Louis Riots and how it launched the national civil rights movement. The History Channel’s website chronicles the Chicago race riot of 1919. PBS’s The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow website offers information on the Wilmington Riots, Atlanta Riots, The Red Summer, and the Tulsa Riots.

If, however, you think your students could benefit from reading raw firsthand accounts, here are a few resource to consider.

- Offering pdfs of original articles, interactive maps, and an oral history of the riots, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch’s archives of the East St. Louis riot are a poignant historical resource and a powerful teaching tool. An introductory editor’s note states, “It is said that newspapers are a first draft of history. Historians take it from there. But on this day, the first and rawest words may speak the most powerfully of those bloody events precisely a century ago.”

- “Riot a National Disgrace.” The St. Louis Argus, Friday, July 6, 1917. Vol. VI, No. 12, page 1. This newspaper article from a black weekly describes the riots from multiple angles.

- “The Massacre of East St, Louis,” edited by W.E.B. Du Bois, The Crisis, September 1917 (Vol. 14 No. 5), pages 219–238. This collection of lengthy firsthand accounts vividly describes the riot’s victims and survivors, including photographs of their injuries.

- “Report of the Special Committee Authorized by Congress to Investigate the East St. Louis Riots,” Congressional Edition, Volume 7444, House of Representatives 65th Congress 2nd Session document #1231, 1918, pp. 1–22. This congressional report chronicles the role community, business, and political leaders played in the riots and describes, and even exhibits, the bias and institutional racism that inflamed the mob.

- “The Congressional Investigation of East St. Louis,” by Lindsey Cooper, The Crisis, January 1918 (Vol. 15 No. 3), pages 116–121. This news account on the Congressional investigation that lead to the report above is illuminating about how black laborers was used to undermine organized labor and thus exacerbated racial tensions.

- “The Situation in St. Louis,” Chapter IX from The Negro Migration During the War by Emmett J. Scott.

- The Tulsa race riots occurred four years after the East St. Louis riots. Walter White, an official of the NAACP, traveled to Tulsa in disguise to survey the damage caused by the riots. The recurring themes in White’s report “The Eruption in Tulsa” shows that the violence and its causes were more pattern than anomaly.

Lynchings and Injustice (Panels 14, 15, 16, 42)

- “About Lynchings,” Chapter 11 in The Chicago Race Riots, July, 1919 by Carl Sandburg describes how racial discrimination in the South and the black press compelled rural blacks to pursue the unknown in industrial centers in the North.

- Thirty years of lynching in the United States, 1889-1918. by National Association for the Advancement of Colored People is a comprehensive and influential study that drove anti-lynching laws. This gruesome data is really unfathomable. The opening summation of facts is especially compelling.

Housing (Panels 31, 46, 47, 48, and 51)

- “Chicago and Its Environs,” Chapter X from The Negro Migration During the War by Emmett J. Scott. This chapter describes the challenges of housing the migrants and the tensions it caused in Chicago.

- “The Housing Crisis in New York City” by Victor Daly pages 61–62, The Crisis, December 1920 (Vol. 21 No. 2). This article looks at the housing challenges the Great Migration caused and how black leaders coped.

- “The Problem” and “Family Histories” by Charles Johnson dissects Chicago’s racial problems, including black and white antagonism over housing, jobs, and crime. (An excerpt from the influential report The Negro in Chicago.)

- “Real Estate,” Chapter 4 in The Chicago Race Riots, July, 1919 by Carl Sandburg chronicles how housing segregation spawned a series of bombings in neighborhoods across Chicago.

- “Negroes and Rising Rents,” Chapter 9 in The Chicago Race Riots, July, 1919 by Carl Sandburg explains how the rapid increase of the black population drove up rents while depressing property values. In addition, this article summarizes ways these challenges should be addressed.

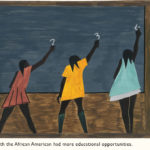

Education (Panels 24, 58)

- “Additional Letters of Negro Migrants of 1916–1918: Letters About Better Educational Facilities,” (Scroll past the first 60 letters on seeking employment.) Journal of Negro History 4, no 4 October 1919. 16 letters to the Chicago Defender seeking better schooling for their children highlight a motivation that drew African American families north.

- “Editorial: The Common School” pages 111–12 and “Education: A Brief Confession of Faith”, by James Dillard, pages 115–116, and “The Year in Negro Education” pages 116–122, The Crisis, July 1918 (Vol. 16 No. 3). These essays highlight the recognized importance of education at a variety of levels. In addition to these essays, note the education-based advertisements. Also note the recurring “Horizon” feature in The Crisis chronicles educational events and advances around the country.

- “Mr. Julius Rosenwald Interviewed,” Chapter 15 in The Chicago Race Riots, July, 1919 by Carl Sandburg, a conversation with the president of Sears, Roebuck & Co., describes the importance of education in gaining blacks their rights and recognition.

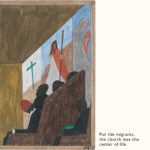

The Church (Panel 54)

- “The Negro Church,” pages 9–11; “The Baptist” by John Snyder, pages 12–14; “The Union of White Methodists” by James Simms, pages 116–122; “The Negro and the Roman Catholic Church” pages 17–22, The Crisis, May 1920 (Vol. 20 No. 1). This issue of The Crisis is dedicated to the growth and the role of the “Black Church” during the Great Migration. Also note the recurring “Horizon” feature in The Crisis chronicles the establishment of congregations and the building of black churches around the country.

- “African American Christianity” summarizes the development of African American religion during the Great Migration and provides a wealth of primary texts.

Tensions between Longtime Residents and Newly Arrived Migrants (Panel 53)

- “The Situation at Points in the East,” Chapter XII from The Negro Migration During the War by Emmett J. Scott. This chapter describes the strains the massive influx of migrant workers had on the social fabric of norther communities.

- This cartoon by Leslie Rogers published in the Chicago Defender, a weekly newspaper for the city’s African-American community, conveys some of the day-to-day tensions that existed between recently-arrived southern migrants and longtime residents. Rogers’ “Bungleton Green” comic strip featured the misadventures of a naive migrant from the South.

How would you use this series of paintings to build on one of your units of study? Please share if you have other ideas on how to teach The Migration Series by Jacob Lawrence as an English/language arts lesson plan.

To me, migration means movement. There was conflict and struggle. But out of the struggle came a kind of power and even beauty. ‘And the migrants kept coming’ is a refrain of triumph over adversity. If it rings true for you today, then it must still strike a chord in our American experience.

This is the story of an exodus of African-Americans who left their homes and farms in the South around the time of World War I and traveled to northern industrial cities in search of better lives. It was a momentous journey. Their movement resulted in one of the biggest population shifts in the history of the United States, and the migration is still going on for many people today.…

To me, migration means movement. While I was painting, I thought about trains and people walking to the stations. I thought about the field hands leaving their farms to become factory workers, and about the families that sometimes got left behind. The choices made were hard ones, so I wanted to show what made the people get on those northbound trains. I also wanted to show just what is cost to ride them. Uprooting yourself from one way of life to make your way to another involves conflict and struggle. But out of the struggle comes a kind of power, and even beauty. I tried to convey this in the rhythm of the pictures, and in the repetition of certain images.

‘And the migrants kept coming,’ is a refrain of triumph over adversity. My family and others left the South on a quest for freedom, justice, and dignity. If our story rings true for you today, then it must still strike a chord in our American experience.

—from the forward of his book The Great Migration: An American Story (1991)

I don’t think about this series in terms of history. I think in terms of contemporary life. It was such a part of me I didn’t think of something outside.…It was a portrait of myself, a portrait of my family, a portrait of my peers.…It was like a still life with bread, a still life with flowers. It was like a landscape you see.

—from the Phillips Collection catalog Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series (1993)

Having no Negro history makes the Negro people feel inferior to the rest of the world.…I didn’t do it just as a historical thing, but because I believe these things tie up with the Negro today.

—from the Museum of Modern Art catalog Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series, (2015)

We don’t have a physical slavery, but an economic slavery. If these people, who were so much worse off than people today, could conquer their slavery, we certainly can do the same thing.… I’m an artist, just trying to do my part, to bring this thing about.

—from the Museum of Modern Art catalog Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series, (2015)

If at times my artworks do not express the conventionally beautiful, there is always an effort to express the universal beauty of man’s continuous struggle to lift his social position and to add dimension to his spiritual being.

I didn’t see a difference in what was happening around me and the stories I painted.

I’m seeing the works for the first time in a number of years and I realize now in looking at them that every time I see them, I see them from a different point of view. I notice the symbols. I didn’t realize that there were so many symbols of railroad stations, bus stations, people traveling! But that is what migration is. You think in terms of people on the move, people moving from one situation to another.…Crossroads, bus stations, and train stations—moments of transition—it certainly was a moment of transition in the history of America and for the race. It’s one of the big movements in our country. And I want to say this, too: I don’t think the blacks in making a movement just contributed to their own development. It contributed to American development. Look at your structure of their cities—the passion, the energy, the vitality. Not always positive—some of it quite negative—but it’s there and I think we have added to, and not taken from, our growth. When I say ‘our,’ I’m using that in a larger context. And I think that we have made a contribution in making this move. Many people tried to keep us out. You had your riots. But we made a tremendous contribution to the American growth, to the American development of America.”

—from the Phillips Collection catalog Jacob Lawrence:The Migration Series (1993)

The following excerpts are from a Smithsonian Archives of American Art oral history interview with Jacob Lawrence October 26,1968 between Carroll Greene (CG) and Jacob Lawrence (JL).

CG: Tell us a little bit about your Migration of the Negro series. What were you trying to do there?

JL: Well to me it was, as I said, many of the things you do early you don’t realize sometimes you add other dimensions to them later. I wanted show I guess it would be what you would call, if this was a European experience, a peasant class in America. It was a great epic drama taking place in America. The Negro has been one of the great I guess focal points of this drama which we as Americans have experienced. We’ve experienced through the Negro as Americans have experienced. We’ve experienced through the Negro experience. So you select things being interested in that and being interested in man and his desire to always better himself. The Negro you cannot pick a better symbol in America to point this up than the Negro experience. So that the Migration I think was an epic which took place and points up this experience definitely. And it was a great dramatic movement, a great drama to it. And of course you have all sorts of social implications there. Everything. The school situation which we talk about to day, the poverty, the people who were successful – and I just don’t want to dwell on all the negative aspects – people moving and people getting a better education. Out of this we have the children of today who are making a contribution in various areas. It was their parents who took part in this migration, came up and worked and so on. These are all things I was trying to say in this, you know, as I look back in retrospect.

CG: So much of your painting, Jacob Lawrence, since the Migration of the Negro series has centered around Negro, or as is popular today, black subject matter as far as content is concerned. Would you care to comment on that?

JL: Yes. I think this is natural thing. My early beginnings, as most Negroes in the United States, has been the Negro experience. This is all I knew at one time was the Negro experience. My whole background, Negro family, Negro community, everything was Negro. So I think it was natural that I would use this symbol for my expression, you see. And of course this is a development. I did do – I think this is very important to what we’re saying here – several years ago I started an American history series which did not pertain strictly to the Negro theme. But I think even my reason for doing it had something with the Negro consciousness because I wanted to show in doing it how the Negro had participated and to what degree the Negro had participated in American history. And that was my reason for doing this. But if you go through the paintings there are very few Negroes in them. There are Negroes with Washington crossing the Delaware purposely so because I wanted to show how he was so much a natural part of the American experience. So that the one time I did move out from this even that was based on my own Negro experience, both historically and my own personal knowledge, my own personal experience.

JL: Well, that’s how this came about. Since then I have continued this involvement. I like to think that I’ve expanded my interest to include not just the Negro theme but man generally and maybe if this speaks through the Negro I think this is valid also. I don’t like to think of myself as just confined to this. I’ll put it this way, although my themes may deal with the Negro but I would like to think of it as dealing with all people, the struggle of man to always better his condition and to move forward, you see, in a social manner however you may interpret this. I like to think that I have grown and developed to where I can see it in this way.

CG: In other words, you’re concerned about, you feel, as has been said of you, you have achieved a kind of universality in what you’ve done artistically. And you use the materials at hand, you use that which you know best.

JL: I would like to think so. I would like to think I’ve been successful in that. Well, I just keep working in that manner. This is what I know. If I can speak, and if my paintings have to make a statement dealing with all mankind I think it has to be done from the Negro point of view. This is what I know. I don’t think the Negro situation is different. It may differ in a small cultural sense but I think all people aspire, all people strive toward a better human condition, a better mental condition generally. And if I can express that through the Negro image I would like to think that I’m making some contribution in this area.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.