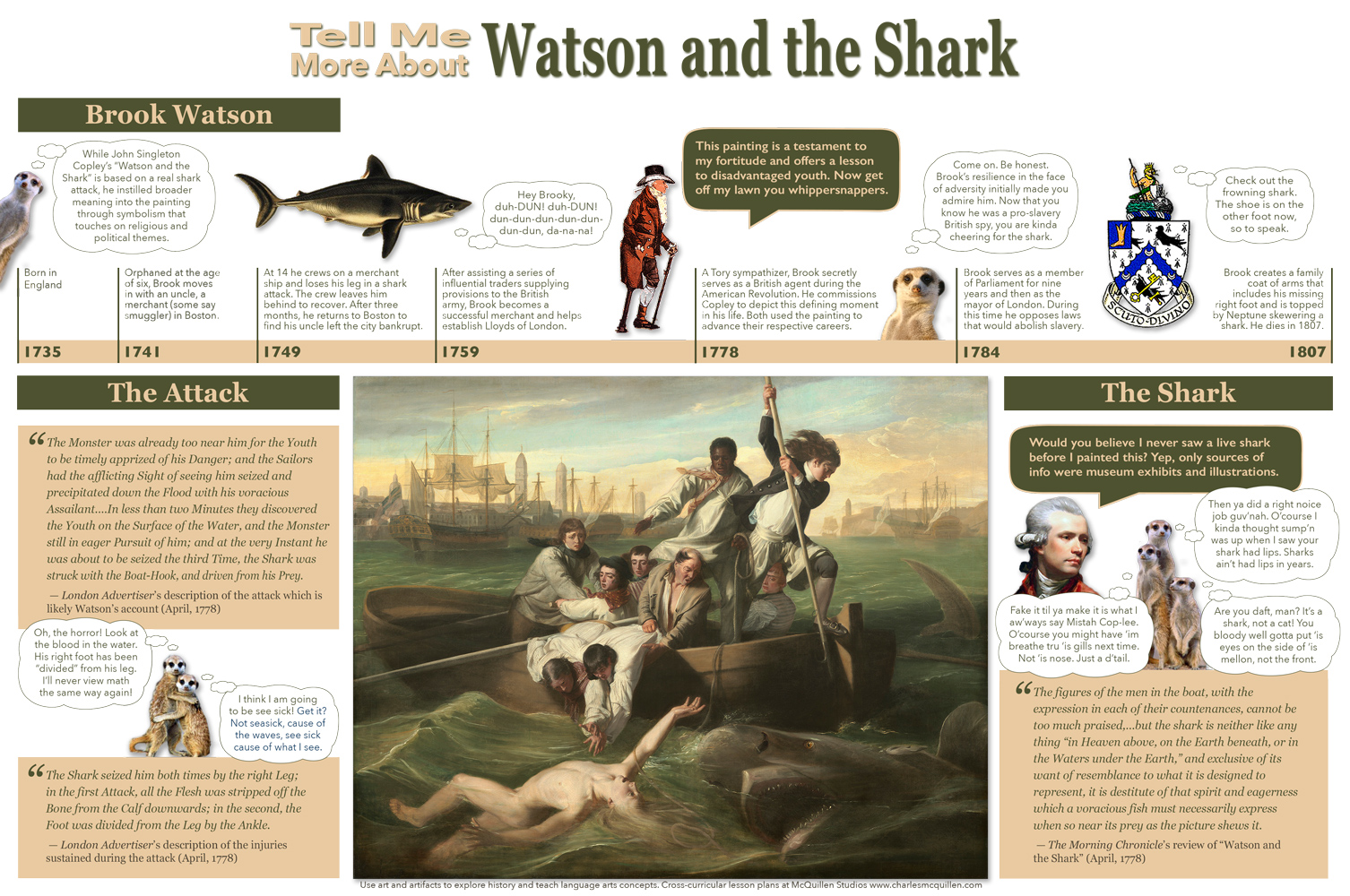

Teach close reading skills, symbolism & allegory, and historical fiction writing with John Singleton Copley’s Watson and the Shark

Two versions of Copley’s Watson and the Shark exist. One is the the National Gallery of Art. The other is in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Access the links for detailed information. Click on the painting for a high-quality image that can be magnified. Learn about the painting’s backstory with an interactive game: Puzzled by Watson and the Shark.

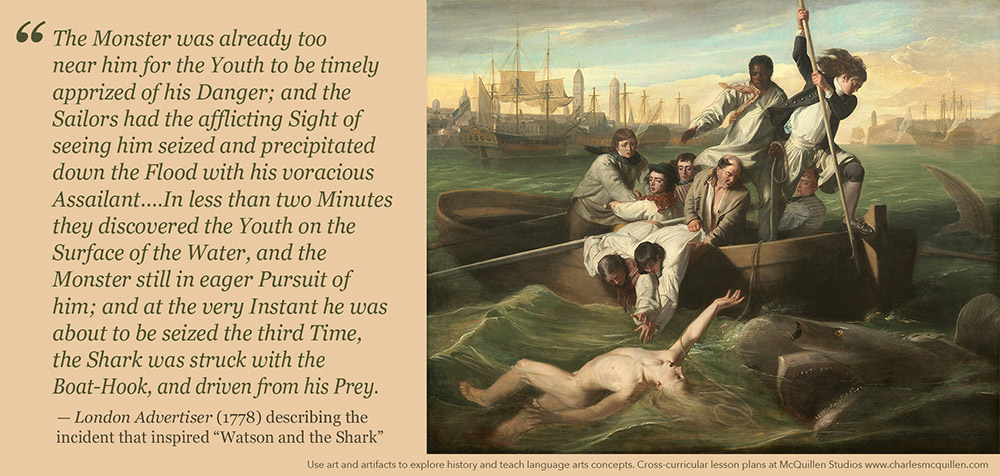

Brook Watson…when a Youth, in a Merchant-Ship, [was] amusing himself one Day by swimming about it, while it lay at anchor…. The men in the Boat, who were waiting for the captain to go on shore, were struck with the Horror on perceiving a Shark making towards him as his devoted Prey. The Monster was already too near him for the Youth to be timely apprized of his Danger; and the Sailors had the afflicting Sight of seeing him seized and precipitated down the Flood with his voracious Assailant, before they could put off to his Deliverance. They however hastened towards the Place, where they had disappeared, in anxious Expectation of seeing the Body rise. In about two Minutes they discovered the Body at about a hundred Yards Distance, but [before] they could reach him, he was a second Time seized by the Shark and again sunk from their Sight. The Sailors now took the Precaution to place a man in the Bow of the Boat, provided with a Hook to strike the Fish, should it appear within reach, and repeat its Attempt at seizing the Body. In less than two Minutes they discovered the Youth on the Surface of the Water, and the Monster still in eager Pursuit of him; and at the very Instant he was about to be seized the third Time, the Shark was struck with the Boat-Hook, and driven from his Prey. This is the Moment the ingenious Artist has selected from the distressing Scene, and has given the affecting Incident the most animated Representation the Powers of the Pencil can bestow. Suffice it to say, in regard to the singular Fate of Mr. Watson, the Shark seized him both times by the right Leg; in the first Attack, all the Flesh was stripped off the Bone from the Calf downwards; in the second, the Foot was divided from the Leg by the Ankle. By the Skill of the Surgeon, and the Aid of a good Habit of Body, after suffering an Amputation of the Limb a little below the Knee, the Youth, who was thus wonderfully and literally saved from the Jaws of Death, received a perfect cure in about three Months.

— An account of the incident that inspired Watson and the Shark from The Derby Mercury, May 1, 1778.

Look at Watson and the Shark. Before reading the excerpt above, tell students the title and ask what is going on in this picture? This painting is rich with details. See how much students can decipher through a discussion. Encourage students to identify the evidence that supports their reasoning. Students should likewise be encouraged to share wonderings and voice confusions. As the conversation slows, explain you are going to read an excerpt that will add context to the painting. This excerpt is a newspaper story from 1778 and was likely planted by Brook Watson to tell his story and promote the painting’s exhibition. Because it is written for another time and culture, this text may seem stilted to many students. Use the painting and context clues in the passage to help students unpack the text. After reading the excerpts ask how does this new insight change your understanding of the painting?

Begin with art history

Watson and the Shark by John Singleton Copley depicts the shark attack on an orphan cabin boy in Havana Harbor. In the scene a tiger shark circles back for a third strike on the hapless Brook Watson. On the first strike the shark had  dragged the fourteen-year-old 100 yards away shredding his right leg at the calf. On the second strike Watson was again dragged under, this time his right foot was bitten off at the ankle. Note the blood-stained water. His crewmates in hot pursuit were able to drive the shark away before it could strike a third time. Miraculously, Watson survived after an amputation just below the knee. Watson overcame these and other early challenges and became a successful merchant, and eventually the Lord Mayor of London. Surviving this attack became a defining moment in Watson’s life, and he even incorporated the lost leg in his family’s coat of arms as if it were a badge of honor. Note that Neptune, the Roman god of the sea fights off a frowning shark. Watson commissioned Copley to paint this scene as a testament to his fortitude and to inspire others to overcome their adversities. In his will he gave the painting to a London school for disadvantaged youth.

dragged the fourteen-year-old 100 yards away shredding his right leg at the calf. On the second strike Watson was again dragged under, this time his right foot was bitten off at the ankle. Note the blood-stained water. His crewmates in hot pursuit were able to drive the shark away before it could strike a third time. Miraculously, Watson survived after an amputation just below the knee. Watson overcame these and other early challenges and became a successful merchant, and eventually the Lord Mayor of London. Surviving this attack became a defining moment in Watson’s life, and he even incorporated the lost leg in his family’s coat of arms as if it were a badge of honor. Note that Neptune, the Roman god of the sea fights off a frowning shark. Watson commissioned Copley to paint this scene as a testament to his fortitude and to inspire others to overcome their adversities. In his will he gave the painting to a London school for disadvantaged youth.

I give and bequeath my Picture painted by Mr. Copley which represents the accident by which I lost my Leg in the Harbour of the Havannah … to be hung up in the Hall of their Hospital as holding out a most useful Lesson to Youth.

John Singleton Copley had been an acclaimed American portrait painter in the years leading up to the American Revolution. And while his neighbors and friends were some of the Sons of Liberty, his patrons were affluent Tories loyal to the King of England. His father-in-law even owned some of the tea destroyed in the Boston Tea Party. Copley tried to avoid taking sides in the brewing conflict, but this professionally treacherous environment eventually compelled him to settle in England.

Watson and the Shark marked a big break in Copley’s career. While portrait work had been lucrative, the largely self-taught Copley hoped to establish his artistic reputation with monumental history paintings. The painting’s celebrated exhibition opened doors at Britain’s Royal Academy. Watson and the Shark also marked an important shift in the history painting tradition. While history painters, such as Benjamin West had moved beyond timeless biblical and classical narratives, they still tapped into epic events of national or military significance. Copley on the other hand, told a personal story and celebrated anonymous commoners. He focused on the sensational as well as on the moral. Rather than clothing his figures in classical togas or regal uniforms, Copley meticulously recreated their modern secular attire and accessories. Through his heroic style and attention to detail he made the mundane monumental and celebrated the individual. In a way, he democratized the grand style of history painting. With its focus on intense emotions, the individual, and the awesome powers of nature, some recognize this work as a precursor for Romanticism.

Look like an art critic

Project this image from the National Gallery of Art and analyze with the accompanying magnifying glass for truly awesome detail. Copley’s second version of the painting is at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. This page provides added insight when it ties the painting to Lin-Manuel Miranda Hamilton.

The Composition

Point out and discuss: The composition is organized around an upright triangle. The shark and Watson are at the base. The shaft of the boat hook serves as one leg in the triangle, while the black sailor’s arm and Watson’s remaining foot mark the other leg. A smaller concentric triangle weds the eyes of the black sailor, the old man in the center, and Watson’s with the shark’s mouth and the sailor on the far side of the boat. How do the elements within this composition enhance the drama of the scene?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: The energy and gestures within the scene push against the edges of the triangle. The alignments of eyes and hands bring a visual order to the painiting and help guide the viewer around the chaotic scene. The old sailor pulling the sailor back into the boat visually anchors the center of the triangle. By contrast, his constrained posture heightens the movement around him. The placid background likewise heightens the sense of activity in the foreground.)

The Figures

Point out and discuss: Copley convincingly renders a range of emotions in this scene. Note how the character’s gestures, but especially the eyes and hands reveal their emotional state. Magnify individual characters in the scene. Describe the emotional state of key characters and how their outward gestures express these inner emotions.

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: Watson’s eyes bulge with shock and horror. He reaches out in blind terror and desperation, more for the heavens than his crewmates. His nakedness and exposed posture underscores his vulnerability. His hair sweeping towards the shark’s gaping mouth and teeth heighten the sense of imminent danger. The two sailors reaching to him express frantic urgency. Their outstretched hands strain to reach him. The strain and urgency can be seen on their furrowed brow and narrowed focus on the boy. The sense of exertion is heightened by their shared gesture. The man in the center of the group, expresses surprise. Like Watson, he looks into the shark’s mouth, but he expresses more amazement than horror. The way he draws the men back into the boat evokes his own emotional drawing in. His arms are shown in a constrained and self-protective posture. The three sailors huddled together on the oar evoke a sense of despair. They appear to clasp on to each other for support and look like they are going to cry in futility. The sailor holding the boat hook like a harpoon expresses rage and even contempt as he targets the shark. His eyes are full of fury, his hands clenched around the boat hook’s shaft. His long hair flies behind him as he thrusts forward. In contrast, the West African sailor is a vision of compassion. He focuses on the boy. His hand that just threw the lifeline, reaches out visually connecting with the boy’s outstretched hand. In comparison to the others, his calm balanced stance is reassuring and soothing. How do these individual responses enhance the picture? These distinct emotional responses add another level of dimensionality to the characters who are already depicted in a three-dimensional fullness. The characteristic emotions are as distinct as the physical traits that distinguish each person in the scene. The characters are so full of life that it seems like you, the viewer, are actually witnessing the event.)

Symbolism and Allegory

Point out and discuss: Artists in the history painting genre regularly leveraged symbolism and allegory as a way to imbue their work with greater significance. While Copley strove to be apolitical, believing that politics distracted him from his art, the historical context of Watson makes it ripe for interpretation. At the time of its painting, the American Revolution is challenging established political and social beliefs and the antislavery movement is growing more vocal. Does this painting lend itself to an antislavery reading?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible interpretations: Yes, the West African sailor is given a position of prominence in the composition at the top of the triangle. He is shown controlling the lifeline thrown to Watson. His hand gesture and the lifeline directly connect him to Watson. His calm compassionate bearing instills in him a sense of power and control.-OR- No, the presence of the West African is not an antislavery reference. The real hero in this painting is the sailor with the boat hook who drives the shark away. His hand and the boat hook are at the apex of the triangular composition. The passive stance of the West African actually heightens the heroic action of the boat-hook wielding sailor.) Does your interpretation change if you knew that preliminary sketches reveal that the black sailor was originally envisioned as a white man with long flowing hair? Does your interpretation change if you knew that Watson made part of his fortune via the slave trade and that as a member of Parliament fought against efforts to end the slave trade? Some view this painting as an allegory for the American Revolution. Others see biblical themes of salvation, resurrection, and a heroic battle against evil. What evidence would you point to to support these interpretations?)

Think like an artist

Now that you have analyzed Watson and the Shark, recreate the scene using only classmates and found materials. If you need inspiration check out how coworkers at Squarespace whimsically recreate classic works of art or how Nina Katchadourian recreates famous Flemish paintings with toilet paper in an airplane’s lavatory.

Does recreating the scene make you view the painting in a new way? For added poignancy consider personalizing the recreation with “a shark” you or your classmates encounter. Document your tableau vivant with a camera phone.

If you try this activity and want to share your camera phone images, forward them to Charles.s.mcquillen@gmail.com and I will gladly post them.

Life Lesson

Fake it until you make it: Copley had little or no experience with sharks, but he didn’t let that get in the way of painting this dramatic scene of a shark attack. Compare Copley’s shark with a photograph of a real shark and you will probably recognize that Copley likely never saw a live shark, drawing instead on drawings, descriptions, and museum exhibits for anatomical guidance. Note that Copley’s shark breathes through nostrils at the end of his nose, not gills. (note the exhaling mist; shark nostrils provide olfactory information and are not used for breathing) Like land-based predators, the shark has forward facing eyes, not on the side of its head as they actually are. And then there are those lips. What his shark lacks in anatomically accuracy, Copley more than makes up for with drama and gusto. The lesson learned, conviction and flare can mask many shortcoming.

Integrating into Your Curriculum

Artists oftentimes use common visual strategies or signposts to alert viewers to significant details in their art. Here are some ideas for using these visual signposts to unpack a work of art. Remember, the close reading skills in art appreciation are similar to the close reading skills taught in reading.

Literature Link: What piece of literature would you partner with Watson and the Shark?

- Esther Forbes’ Johnny Tremain tells the story of another 14 year old overcoming hardships and physical trauma from the same time period.

- Herman Melville’s Moby Dick is another example of allegory and Romanticism and vividly describes sea faring and the whaling industry.

Writing opportunity: historical fiction and graphic novel. Brook Watson is an especially colorful historical figure who merits further research and writing. Through Internet research, students could collaborate and tell a more complete story of this complicated and polarizing man. You could add some art and turn it into a graphic novel. Here are some sites to help you get started.

- The Story of Brook Watson by Clarence Ward is one of the most comprehensive accounts I have found.

- The History of Parliament cite records Watson’s argument against the abolition of the slave trade.

How would you use this painting to elaborate on one of your units of study? Please share if you have other ideas on how to teach Watson and the Shark by John Singleton Copley as an English/language arts lesson plan.

The Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, 25 April 1778.

One of the most striking pictures in the Great Room is a painting by Mr. COPLEY, of a boy attacked by a shark, and rescued by some seamen in a boat. This piece is one of those frequent proofs we meet with of great abilities joined to little judgment. The figures of the men in the boat, with the expression in each of their countenances, cannot be too much praised, and at the same time the other parts of the picture cannot be too severely reprehended. The Black’s face is a fine index of concern and horror. The same feelings are also very forcibly impressed on the looks of the sailors; but the shark is neither like any thing “in Heaven above, on the Earth beneath, or in the Waters under the Earth, ” and exclusive of its want of resemblance to what it is designed to represent, it is destitute of that spirit and eagerness which a voracious fish must necessarily express when so near its prey as the picture shews it. Add to this: the sea should be of a foam with the lashing of the shark’s tail, and the boat, as almost every man leans on one side, in order to save the boy, ought to lie nearly gunnel to, whereas the waves are as placid as those of the Thames when there’s little or no wind, and the boat as steady as if it was in that sort of safe sea which is occasionally exhibited on the stage of Sadler’s-Wells.

The St. James’s Chronicle; or, British Evening-Post, 25-28 April, 1778.

Genius and Love … have been very friendly to Mr. John Singleton Copley, in his Representation, No. 65, of some Seamen, saving a Lad from the Attacks of a Shark. The Drawing of the Figures is correct and firm; their various Actions, and every one of their Features, such as the Terror of the Situation requires, and they are expressed in so excellent and masterly a Manner, and the Whole is so well coloured, that we heartily congratulate our Countrymen on a Genius, who bids fair to rival the great masters of the ancient Italian Schools. The beautiful Boy, just disintangled from the ravenous bloody Monster, which had tore away one of his Legs, cries for that Assistance, which every one of the honest Tars hurries to give without Loss of Time. The Boatswain, an elderly Man, has catched one of his Arms in the Noose of a Rope, and he pulls it clear with Prudence and Caution. Two Sailors, brave Fellows, Horror bristling their Hairs, and the Eagerness of a compassionate good Heart for the poor Sufferer in their Faces, lean over-board, and stretch their Hands to help him in so dangerous a Manner, that the Beholder must tremble for Fear of their falling overboard, and their becoming a Prey of a young Shark, that flies against them, swift as lightning, with open Snout, and inexpressible Greediness in his flaming Eye; the same Moment that a fine young Sailor, standing at the Helm, strikes at him with a lifted Boat-Hook. An idle Black, prompted by the connate Fear of his Country for that ravenous Fish, leans backward to keep the Gunnel of this Side of the Boat above Water; herein he is assisted by two Rowers on the other Side, who, less engaged in the more noble Part of the other Actors, have of course their Compassion and Curiosity stronger expressed in their Features. The whole makes an excellent Group, by the Dampness of the hazy hot Climate, well parted from the Background, in which some English Men of War, and the Moro Castle at the Havannah, serve to determine the glorious Time, and the Place where our Tars so nobly exerted themselves. There is one Thing which in our Opinion lessens the Effect of the whole. The horizontal Line being taken too high, makes it somewhat heavy, and brings the Hulks of the Ships, and the Batteries of Fort Moro, almost in Contact with the upper Part of the Canvass: But we remember that a very fine Picture of Nicholas Poussin, in the Gallery of the Landgrave of Hesse, representing the Murther of Pompey in the Harbour of Alexandria, is subject to the same Reproach, and we are very apt to believe in both Pictures, it arose from Circumstances which it was not in the Power of either of the Artists to avoid; they would have done it very easily if they had been allowed to give their Canvass a greater height.

The St. James’s Chronicle; or, British Evening Post, 28-30 April, 1778.

Our correspondent has desired us…to rectify an Inadvertency which his Candour acknowledges to have been guilty of, in respect to the Boatswain and the Black, in Mr. Copley’s excellent historical Composition, the one being rather tenderly concerned for the two Sailors, who lean overboard, and vociferous to his Crew; and the idle Black holding the Rope loose, which the Boatswain seems to have flung over one of the Sufferer’s Arms. To this we add, that Mr. Copley is a native of America, and that he has sent some excellent Portraits to the former Exhibitions, before he had been improved by a academical Education in Europe.

The General Advertiser, and Morning Intelligencer, 27 April 1778.

A boy attacked by a shark…, by John Singleton Copley, deserves particularly to be praised. Its whole is very fine, though there are some inaccuracies in its parts. The story is well told. The point of time is, when the shark is darting upon him a third time, two men are in the act of catching him, a third is striking the shark. So far the design is perfect. But we must suppose, that at that instant of time, no horror in beholding the object would prevent seamen from acting to his rescue. It would not be unnatural to place a woman in the attitude of the black; but he, instead of being terrified, ought, in our opinion, to be busy. He has thrown a rope over to the boy. It is held, unsailorlike, between the second and third finger of his left hand and he makes no use of it. There is not a blast of wind stirring. The colours and sails of the distant ships, as well as the waves of the present sea, are unruffled; and yet, to add to the expression, the hair of the sailor, who is darting at the shark, is blown to a great degree. Notwithstanding these inaccuracies, and they are merely so, the piece is very fine. He has improved upon the horror of the shark, by leaving it unfinished, and we think he studied narrowly the human mind in this circumstance. No certain and known danger can so powerfully arouse us, as when uncertain and unlimited. He gives the mind an idea, and leaves it to conceive its extent.

A reviewer in the “General Advertiser” of April 28, 1778, criticized the artist for the futile way the rope is handled, but we may believe that the uselessness of the rope was intentional, and that Copley meant to signify Watson’s dependence on God for his salvation.

While this was lifted from Irma Jaffe’s Copley’s `Watson and the Shark’ (please respect attributions) thanks for sharing this. This reference helped me to find other reviews from the time. Here (and above) are four online reviews that may be fun to share with students.Unlike some contemporary reviews that view the painting as a religious allegory, these reviews critique the practical accuracy of the depiction, insights uniquely suited to people who would witness like events. Would any, other than those raised in a sea faring nation, offer such sensitive insight into the sailor’s mannerisms or the depiction of the water. The reading of the black sailor in these reviews is also intriguing. “It would not be unnatural to place a woman in the attitude of the black; but he, instead of being terrified, ought, in our opinion, to be busy.” “…and the idle Black holding the Rope loose,…” “An idle Black, prompted by the connate Fear of his Country for that ravenous Fish, leans backward to keep the Gunnel of this Side of the Boat above Water…” Such a harsh assessment for a man I see as a pivotal figure offering a potential lifeline and serene compassion during a time of turmoil. Idle bystander or an instrument of God’s saving grace? Gotta love how sharing interpretations add layers of insight to a work of art—and the viewer.