How Notice & Note signposts support art appreciation and visual literacy

The Lincoln Center Education’s (LCE) Capacities for Imaginative Learning emphasize authentic experiences with the arts—music, theater, dance, and the visual arts. For the sake of detail and clarity, this post will focus on the visual arts.

The LCE’s first two capacities are about identifying and articulating layers of detail on a visual and experiential level. Students are called to visually, emotionally, and physically respond to a work of art. In a previous post I noted how Stephanie Harvey and Anne Goudvis’s active literacy instruction developed skills needed to achieve these capacities, especially how they taught students to listen to the inner conversation that naturally occurs in reading nonfiction texts and how to build on this internal dialogue.

Capacities 3, 4, and 5 take a more inquiry-based stance as students experience a work of art by asking questions, making connections, and identifying patterns. This visual unpacking can be an overwhelming proposition for students as they try to discern what details are integral and what details are incidental to a work of art. Here again, we may find that established literacy instruction offers help developing these capacities.

In their acclaimed book Notice & Note: Strategies for Close Reading, Kylene Beers and Bob Probst introduce six “signposts” that alert readers to significant moments in a work of literature. Learning first to spot these signposts and then to question them enables readers to explore the text, any text, finding evidence to support their interpretation. Understanding how these signposts support the close reading of literature could inform how we can help students look at and “read” a work of art.

The 6 Notice & Note signposts and their anchor questions

The signposts help readers recognize significant moments in a work of literature. The anchor questions helps readers take note and read more closely.

- Contrasts and Contradictions: When a character says or does something that’s opposite (contradicts) what he has been saying or doing all along, you should ask yourself, “Why is the character doing that?” The answer could help you make a prediction or make an inference about the plot or conflict.

- Aha Moment: When a character realizes, understands, or finally figures something out, you should stop and ask yourself, “How might this realization change things?” If the character figured out a problem, you probably just learned about the conflict. If the character understood a life lesson you probably just learned the theme.

- Tough Questions: When a character asks himself a really difficult question, you should stop and ask yourself, “What does this question make me wonder about?” The answer will tell you about the conflict and might give you ideas about what will happen later in the story.

- Words of the Wiser: When a wiser character, who is usually older, offers advice or an insight about life to the main character, you should ask yourself, “What is the life lesson here and how might it affect the character?” Whatever the lesson is you’ve probably found a theme for the story.

- Again and Again: When you notice a word, object, or situation mentioned over and over, you should stop and ask yourself, “Why might the author bring this up again and again?” The answer will tell you about the theme and conflict, or they might foreshadow what will happen later.

- Memory Moment: When the author interrupts the action to tell you a memory flashback, you should ask yourself, “Why might this memory be important to the forward progression of the story?” The answers will tell you about the theme, conflict, or might foreshadow what will happen later in the story.

To learn more about these signposts, including author videos and sample chapters, visit http://heinemann.com/NoticeAndNote/.

To appreciate the significance of these signposts in transforming classroom practice search Notice & Note on Pinterest. The classroom adaptations will amaze.

Even though these are literature-based signposts, some can directly inform how we view and interpret the visual arts.

Consider contrasts and contradictions for example. As an artist I regularly rely on jarring juxtapositions to surprise and awaken the viewer. In Silent Suburb the faux entrance holes in the rows of sturdy birdhouses startle the viewer and alert them to a comparable situation in the environment. In the Recipe/Storm Drain Stenciling Project the wildly out-of-place family recipes painted next to storm drains catch the passerby off guard and make them look at the storm drain in a new light. Looking for and puzzling through these contradictions would help students read these pieces on a deeper level.

Again and Again can likewise translate to the visual arts since artists strategically use symbols, shapes or colors throughout a composition. When viewers encounter these repetitions they should ask themselves, “How does this repetition add emphasis, create pacing, or guide my eye?” The answer will alert viewers to patterns and visual hierarchies within the piece. My Stacking a Line installations use repetition to draw lines across the landscape and highlight characteristic features of the environment.

Since these are literary signposts, new signposts will need to be developed to unpack the visual arts. Kylene and Bob’s framework can still serve as a model in this effort. First we identify a slew of these signposts, and then we pare them back to the most significant. I will humbly submit a few to get us started.

Leonardo da Vinci’ s “Mona Lisa”

Find the Triangle Artists have long used subtle triangular shapes to organize and prioritize their compositions. When viewers encounter these triangular configurations they should ask, “Who is in the triangle and how are they positioned in relationship to others.” They might also ask, “Is the base of the triangle at the bottom creating a sense of grounded stability or is the triangle upside down or asymmetrical creating a sense of tension or motion.” The answers to these questions may highlight the focal point of the piece and establish a hierarchy of its parts. A classic painting that would apply the Find the Triangle signpost is Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. The serene look on the sitters face and her calm reserved pose are enhanced by a strong, balanced triangular composition that emphasizes stability and control.

Barbara Kruger’s “Your Body Is a Battle Ground”

That Reminds Me of Something Meaning and interpretations are built on an artist’s and a viewer’s background knowledge. Students should be sensitized to this and when they sense something familiar, they should ask themselves, “Where do I know that from and how does it inform my understanding of the piece?” The answer may establish associations that add layers of insight and understanding to a work of art. A classic print that would apply the That Reminds Me of Something signpost is Barbara Kruger’s Your Body is a Battle Ground. In this piece that explores gender, identity, and power issues, Kruger uses mass communication and advertising techniques and iconography to challenge and reframe the mainstream media’s cultural constructs. This piece will have added meaning for viewers who are familiar with magazine design and advertising.

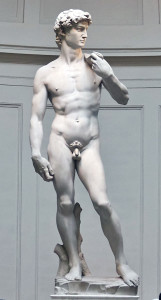

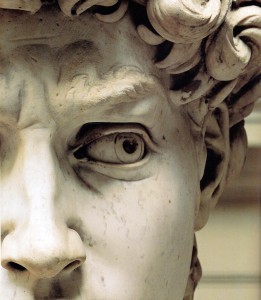

Be a Palm Reader (the catchier the turn of phrase the more memorable?) Hands—and eyes—can be especially telling in a work of art. When the artist carefully render these ask yourself, “What do the hands hold” or “Where are the hands pointing” or “What gesture do the hands display.” The answer will likely highlight a symbol or emotion significant to the work of art. A classic sculpture that would apply the Be a Palm Reader signpost (and contrasts and contradictions) is Michelangelo’s David. His hands are at rest. One hangs at his side. One cradles his all-important sling. This relaxed pose stands in contrast to his eyes that burn with fury as he looks at the oncoming Goliath. This marks the pregnant moment when his mind resolves to battle before his body reacts.

Creating visual arts signposts to share with students will make your mind swim with possibility. Jump on in, the water is fine.

This site’s guiding principles extends this exploration into imaginative learning practices.

For more information on LCE’s Capacities of Imaginative Learning, visit www.LincolnCenterEducation.org

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.