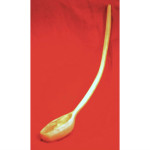

My Yupik and Inuit students taught me traditional direct carving techniques in antler, ivory, and soapstone. We used the materials at hand to craft tools and we embellished them with the images of the animals around us.

I began making art, and teaching, while serving in the Jesuit Volunteer Corps at St. Mary’s Mission, a native boarding school on Alaska’s Yukon Delta. And while I credit my students with introducing me to direct carving, they probably had a bigger impact on shaping my approach to teaching.

Originally, my classroom responsibilities focused on teaching social studies classes—current events, world geography—and the Alaskan Native Land Claims Settlement Act. Without formal teacher training, my initial teaching largely mimicked the traditional ways I had been taught. The rows of desks were orderly and the content flowed from the teacher at the front of the room. Then, a staffing change added art teacher to my responsibilities. Comfortable with art history and working with my hands, but unfamiliar with studio art practices, I entered this classroom with more humility than my other social studies classes. Instead of beginning with a listing of my expectations, I asked the students what we should do. An older student said, “Lets carve,” and proceeded to pull out files and rasps for himself. I pulled out files and rasps for the others. As he selected soapstone and began to carve, I helped others do the same. He lead, I facilitated, and the rest of the class eagerly joined in. The classroom environment was electrifying. While the room was big, all the students huddled together, shoulder to shoulder. As the soapstone flew and rocks became sculptures, the students openly discussed what they hoped to achieve and offered feedback and new found carving tips to each other. Out of this collaboration, community blossomed.

As the rhythm of the class developed I regularly found teachable moments and windows of opportunity to extend the learning. We found inspiration and guidance in books about other Eskimo carvers and carvers from other cultures. In the context of their work, I introduced the elements and principles of art. I would regularly brainstorm with individuals and small-groups ways of overcoming momentary hurdles. As they polished and shared their first simple sculptures, I challenged them to try another more sophisticated sculpture, this time with overlapping forms. Rather than being the sage on the stage, I learned the benefits of being a guide at the side. Years later, in working with Don Graves, Lucy Calkins, and Nancie Atwell, I learned that I had stumbled onto the workshop approach to teaching.

In a way, direct carving and workshop teaching have a lot in common. They both adopt a constructivist mindset that builds on established traits. They both emphasize being responsive and opportunistic as part of their process. And they both recognize that collaboration and dialogue are integral in realizing a transformative opportunity. While it is never wise to follow a metaphor too strictly, they can help ground and broaden your thinking, and in regards to this site, this is not a bad metaphor to reflect on.

One way for students to reflect on the internalized values that shape their own aesthetic and approach to art is by exploring how other people’s art manifest their cultural values.

Here are two sites that could support a discussion on indigenous art and the cultural values they reflect.

- Alaskan Native Heritage Center is a cultural center and museum dedicated to the exploration of Alaska’s indigenous people, past and present. Don’t miss the contemporary art.

- Canada’s First People site explores indigenous cultures through historic artifacts and cultures.

Both sites offer a consistent framework for exploring a culture and a rich array of artifacts and art that manifest these values.

You could apply the same framework to explore the students’ own values.