Teach close reading skills, the importance of a unified composition, and regionalism with Thomas Hart Benton’s America Today

Thomas Hart Benton’s America Today is part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection. Visit their website for detailed information and for high quality images.

Thomas Hart Benton’s America Today is part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection. Visit their website for detailed information and for high quality images.

These paintings give one a sensation like that of looking out of the window of a train speeding through cities past factories and mines, through farmland and woods, over prairies, across rivers. They convey a sense of the restless, teeming tumultuous life of this country, its wide range of contrasts, and its epic proportions. The keynote of the conception of American life embodied in these murals, is a furious vitality, finding expression particularly in productive labor.…His design is as insistent as jazz or the beat of machinery, seeming in tune with the speed and emphasis of modern American life. These energetic qualities, which are part of the force of Benton’s work, also account for its limitations. In his anxiety to make every element in his pictures powerful and dynamic he tends to overreach himself, forgetting that where every thing is emphasized, nothing is emphasized; and that uniform over-statement produces not power but monotony. …It is easily understandable that to many these murals may seem in very bad taste. But their positive virtues are considerably more important than the negative virtues of reserve and refinement which they lack. It is fitting and healthy for an artist of genuine force to begin by being over strong and over bumptious; the minor virtues will undoubtedly come in time. The important thing is that Benton possesses vitality and a genuine creative gift—qualities not too common.

—Lloyd Goodrich,“The Murals of the New School,”Arts 17, no. 6, March 1931.

Here are the locomotive and the Diesel engine, the dynamo, the dam, the spillway, all in full operation, all requiring the perpetual labor of man; great rivers with their traffic carry us up and down a land of ever-changing horizons, a land full of men who are building a young nation toward unglimpsed future goals… These murals may well shock the timid or the beholder whose thought pursues an academic groove; for they are aflame with high keyed color, often garish in the fidelity of their response to a native drama as yet so largely raw and so youthfully impulsive. The impact of the room that contains them may well be terrific. Perhaps only the strong may enter there without permanently parking hope of survival at the door. And yet for all their crude, harsh vigor of life, the paintings are instinct, too, with fineness and tenderness and an abundant love. In viewing these murals one feels that at last Thomas Benton is really speaking out with the full force of his spiritual bellows.

—Edward Alden Jewell, “Orozco and Benton Paint Murals for New York. Gesso and True Fresco: Artists Produce Work in the Modern Spirit for the New School for Social Research,” New York Times, November 23, 1930.

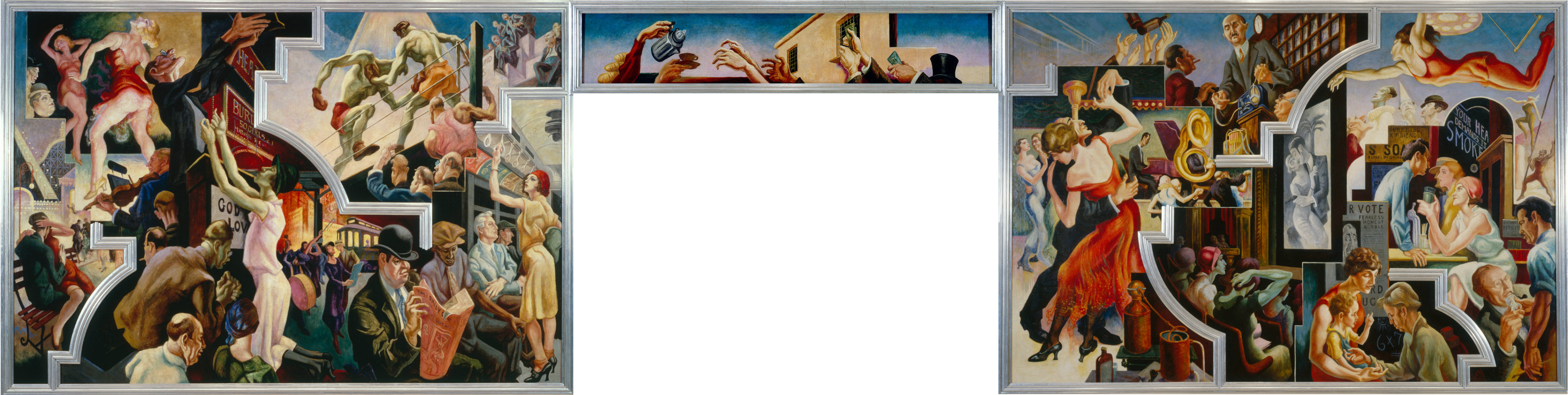

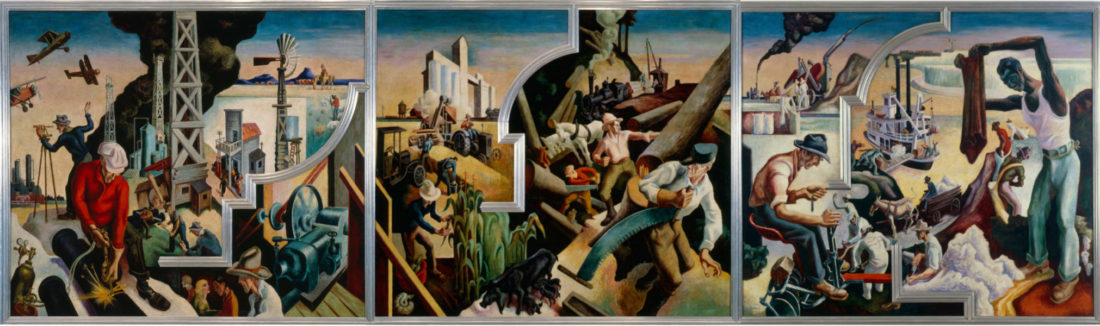

Look at America Today. Before reading the excerpt above, tell students the title of the piece and ask what is going on in this picture? This is a large, wraparound mural so you may have to talk through the parts. First set context by showing the three-wall image and explain that, for a more detailed view, you will look at each wall separately. (Click on the images to isolate an image.) As the viewer enters the room they face the largest panel America Today: Instruments of Power. The “west” wall contains three panels: Deep South (cotton harvesting), Midwest (lumberjacks and farmers), and Changing West (oil and movie production). The “east” wall contains three parallel panels: City Building (construction workers), Steel (steel production), and Coal (miners). The back wall the viewer enters through has two panels on either side of the walkway, City Activities with Subway and City Activities with Dance Hall. These two panels are joined by a third panel over the entrance called Outreaching Hands. While the images are familiar and fairly straightforward there is a lot going on. See how much students can decipher through a group discussion. Encourage students to identify the evidence that supports their reasoning. Students should likewise be encouraged to share wonderings and voice confusions. As the conversation slows, explain you are going to read two reviews by art critics who viewed the panels at their original site in the New School for Social Research. This mural is now displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. After reading the excerpts ask how does this new insight change your understanding of the painting?

Note: To facilitate discussion, you may want to explain that even though these reviews are generally complimentary, the reviewers also express a number of critical insights. A two-column anchor chart titled strengths and weaknesses can help you sort these statements out. Ask students if they agree with these assessments.

Begin with art history

Thomas Hart Benton was born (April 15,1889) in Neosho, Missouri into a family of prominent lawyers and politicians. He was named after his great grand-uncle, one of Missouri’s original senators who was best known as an architect of Manifest Destiny and shooting General Andrew Jackson in a brawl. Benton shared his namesake’s expansive view of the United States and feisty nature. Against his father’s wishes Thomas pursued an art career becoming a illustrator for the Joplin American newspaper at the age of 17. Using art to tell stories remained a driving concern in his art making throughout his career.

During his 20’s, while living in Paris and New York City, Benton “wallowed in every cockeyed ‘ism’ that came along.” It wasn’t until WWI, when he served as a naval draftsman that he began to find his artistic voice. In this role, objective realities and the mechanical contrivances of machines and buildings consumed him. As Benton explained in his autobiography,

I found that it was not necessary to look into myself and my “genius” to find interesting things. I had found that these things existed in the world outside of myself and that it made no difference whether I had any genius or not. I was released from the tyranny of the prewar soul which everybody so assiduously cultivated in the world of art and which was making of it such a precious field of obscurities. I proclaimed heresies around New York, talked on the importance of subject matter, then under the rigid taboos among the aesthetic elite, and ridiculed the painters of jumping cubes, of cockeyed tables, blue bowls, and bananas, who read cosmic meanings into their effusions. In a little while, I set out painting American histories in defiance of the conventions of our art world. I talked too much, and trod on all sorts of sensibilities and made enemies. But I didn’t care. (An Artist in America, ©1968, page 45)

This “objective” aesthetic coupled with his outspoken manner earned him the enmity of many in the established art community. His unflinching view of American history that depicted the celebrated and the infamous alike earned him equal condemnation from the political left and right. Benton described how his New School mural excited controversy from across the spectrum.

My finished job drew down a storm of criticism. It was called ‘tabloid art,’ ‘cheap nationalism,’ ‘modernist effrontery,’ and a lot of other nice things. Practically all those tricky word combinations for which New York critics are so justly famous were hurled at my work. Conservatives whaled me for ‘degrading’ America, purists for representing things, and the radicals were mad because I didn’t put in Nikolai Lenin as an American prophet. (An Artist in America, page 248)

Benton reveled in controversy in part because he was naturally outspoken and enjoyed the verbal jousts and in part because he knew provocative headline-grabbing statements would raise his public profile. Benton cultivated a persona of a hard-drinking hillbilly who stood up against the elite art community and made art of and for the common man. He regularly went on lengthy sojourns across the country sketching the lives and lore of the marginalized and ignored. The New School mural project grew directly out of these sketches.

While Benton was midlife (age 42) when he created America Today, it launched his career and established a signature style of art making that would characterize his most renowned work. Benton transformed history painting creating heroic depictions of common laborers. Through his emphasis on bulging muscles, writhing forms, intense colors, and dynamic internal rhythms, Benton created his own brand of expressive realism that was made even more theatrical by its enveloping compositions and grand scale. His dramatic chiaroscuro and sculptural approach to painting grew out of the three-dimensional clay models he created to help solve compositional problems. While he drew heavily on Renaissance techniques, Benton’s focus remained squarely on cultivating a distinctly American aesthetic that that has been called messy, vulgar, complicated, inspirational, and democratic.

Look like an art critic

America Today is housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Visit their website to see more details and learn more. Thanks Metropolitan Museum of Art!

Unifying features and lines

You don’t generally see a mural all at once, or you may see it all at once but you likely exploit it by looking at one part and following it along. So you have to design a mural knowing that the eye is going to be moving all the time over these spaces and you have to arrange it so the eye will follow certain lines so you will have a sense of unity when you get through with it.

—Thomas Hart Benton, from Ken Burns America Collection, PBS Home Video, 1988

Point out and discuss: It took Benton nine months to create America Today. The first six months were spent coming up with the composition’s grand design. It only took three month to execute the painting. Since the composition was artistically so demanding it deserves added scrutiny. What design elements unify America Today? How does Benton use repeating lines and design elements to draw the viewer’s gaze across the entire composition and how does that serve his intentions?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: All of the panels share the same blue sky and the same white clouds and light that become more diffuse as it nears the horizon. These colors become unifying bands across the panels. While the horizon line shifts, all of the panels share the same center of gravity that anchors key elements to the base. All of the panels share an aluminum-leaf molding that accentuates repeating curves and right angles throughout the composition. These molding elements also connect to and highlight the aluminum-foil frame that contains the mural as a single entity. The shared scale and gestures of the people, and the common mechanical shapes and structures create parallel images that can be read in multiple sequences. The east wall offers a good example of how a strong curving line unifies the three panels. The back and arm of the black jackhammer operator curves up and aligns with the curve of the aluminum-foil molding. On the next panel the downward curving molding aligns with the back and arm of the iron worker. On the third panel the upward curve aligns with the miner’s hunched back. These alternating sweeping curves undulate across, and bring cohesion to the three panels.

Shared elements likewise cut across frames tying panels together. A sheet of wood and a 2×4 join the Changing West and the Midwest. The green ground and the dark structure connect the Midwest with the Deep South. Even when they are not the same element, shared alignments join panels. Consider how the iron worker’s lever in Steel aligns with a girder in Coal. Orange elements across the east wall direct the viewer’s gaze up and down in a zigzag pattern across the three panels. Lines connecting the foreground to the background likewise create a three-dimensional zigzag across the three panels. The compositional elements work in concert to drive the viewer’s gaze up and down, in and out. These three panels are book ended by the same red shirt and the cross-section of the hill in Coal mirrors the bent arm of the jackhammer operator.

Benton is a visual storyteller. These compositional elements help the viewer follow and weave together the multiple story lines of America’s working class. For example, in the middle of Steel the curve of aluminum-foil molding extends up through the twisting steelworker’s back and arms. The line then transfers to his lever and across the panel to Coal where train tracks usher the line up through a handrail into another molding element and across the slumped miner’s back. These carefully crafted elements illustrate processes and highlight relationships between interrelated systems and workers. Like the compositional elements, the efforts of each worker are supported by others in a web of shared productivity.

The depiction of motion

Point out and discuss: In his review above Goodrich writes that America Today conveys, “a sense of the restless, teeming tumultuous life of this country… American life embodied in these murals, is a furious vitality.…His design is as insistent as jazz or the beat of machinery, seeming in tune with the speed and emphasis of modern American life.” How does Benton evoke the sense of pulsating motion in a static painting? How does Benton’s expansive view of mural painting and wrap-around composition accentuate this sense of motion?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: The machines in Instruments of Power exhibit a Disney-like representation of motion. The train lurches ahead with cartoonish elongated wheels, its smoke and steam curling back. The airplane propeller blurs in rotation. The water swirls with white streaks as it drives the turbine or gushes from the spillway. The human figures in the other panels show a more nuanced representation of strain and motion. Bulging muscles, elongated torsos, and twisting bodies create a sense of mounting tension and torque. Billowing smoke, falling trees, flowing molten metal evoke a visceral transformation. The concentration of action-packed images compressed into rigid frames suggest a pending explosion. The dramatic compositional shifts between a distant background and a leap-off-the-wall foreground further heighten the visual energy.

The regularity of the panels and the aluminum-foil frames likewise instill a pulsing rhythm. As Goodrich explained in his review, these are like windows of a train as it clicks down the track. Or, the segments could be read as a spliced together film stills for a giant whirring projector. The silver molding could be read as arching electrical charges across metal frames. Even the viewer brings motion to the installation. The viewer needs to pivot and spin to take in the life-size panels that wrap around the room, their eyes twitching to focus.

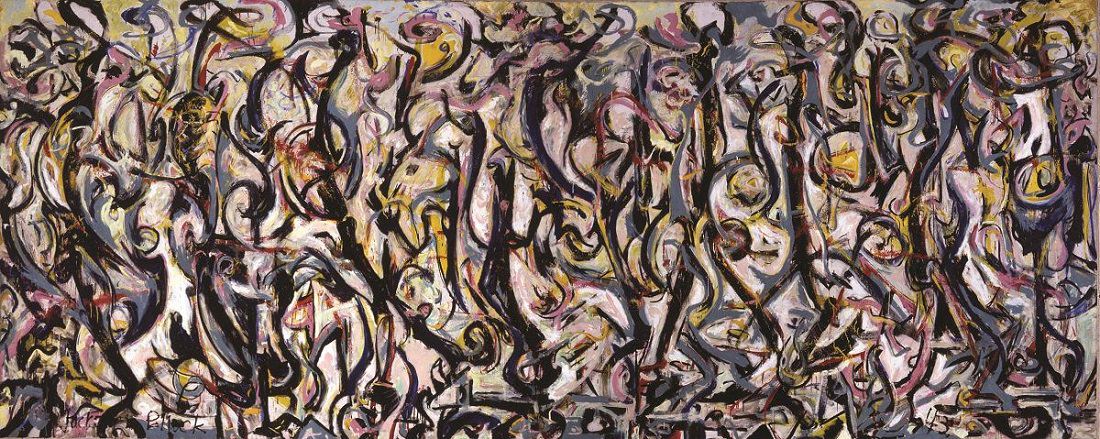

Compare murals by Thomas Hart Benton and Jackson Pollock

Point out and discuss: The Benton family had an especially close relationship with Jackson Pollock, one of Benton’s students and the troubled artist who went on to become the foremost Abstract Expressionist, an academic style of art that pushed Regionalism from prominence. There has been much speculation about Benton’s influence on Pollock’s work. A defensive Pollock declared that Benton simply served as a force to rebel against. Oedipal arguments aside, it may be fruitful to compare seminal works from each artist—a 3-panel wall (8’x30’) from America Today (Pollock modeled for the iron worker stoking the furnace) and Pollock’s Mural, the 8’x20’ painting commissioned by Peggy Guggenheim that became a landmark example of Abstract Expressionism. It may support the discussion to let students know that Pollock said his Mural was driven by a vision of a stampede of cows, horses, antelopes, and buffaloes. As Pollock explained, “Everything is charging across that goddam surface.” While the differences may be more evident, the similarities may be more telling. How are these two paintings different? How are these two paintings similar? In what ways do you think Benton’s America Today may have influenced Pollock?

Turn, Talk, and Report Back (Possible answers: DIFFERENCESs: Benton’s murals are representational and figurative while Pollock’s Mural is more abstract. Pollock’s painting is flat and accentuates the inherent qualities of the paint. Benton’s chiaroscuro makes his mural sculptural (three dimensional), the paint is a plastic vehicle for telling a story. Benton’s touch is more controlled and exacting while Pollock’s touch seems more fluid and intuitive. SIMILARITIES: Both paintings are large, enveloping the viewer in a raucous immersive viewing experience. There is no central point of focus or visual hierarchy as the viewer’s eye is propelled from one element to the next. While both painting have details that invite scrutiny, the all-over composition demands distance to take in the painting’s full expanse. Both compositions build on a grand design of repeating lines, balance, and sequence. Both paintings have a pulsating energy with rhythmic, interlocking forms that strain and heave across the entire space. Pollock’s sweeping, gestural lines echo Benton’s elongated figures and their sinuous, twisting forms. Dynamic energy and frenzy inspired both artist—Pollock inspired by an animal stampede and Benton filled his mural room with an equally frantic human stampede of burgeoning industrialization. Both paintings share a muscular, lapel-grapping quality that speaks to the artists’ brash machismo and emphatic self-confidence. These artists don’t seem as opposite as Pollock would initially lead one to believe. Their expressive lines, over-all composition, and chest-thumping temperament suggest their work is distinguished more by an aesthetic shift than an oppositional divide. While these artists are expressing their own distinct point of view, they are framing their positions around shared vocabulary and common interests.

Think Like an Artist

Mannequin Challenge + Panoramic Photo = Living Mural With a group of people, stage an expansive real-world scene with exaggerated gestures and expressions. Like Benton, tell a story through a carefully crafted composition. Make sure the alignment of key visual elements draw the viewer throughout the scene. Once the composition is established record your scene with a smart phone camera on panorama setting. Review the image. Consider ways to use line, color, and space to enhance the composition. Also pay close attention to the parts. How can each part be made more expressive or theatrical? Take another picture. Compare your images. Discuss which is better and why.

Life Lesson

Get away from the daily grind and let natural rhythms realign your thinking. Early in his career Benton and his wife-to-be Rita began a 50-year annual tradition of summering on Martha’s Vineyard, painting and sketching “the old Yankees on the island.” Benton explained the impact this time away had on his art.

It was Martha’s Vineyard that I really began to mature my painting—to get a grip on my emerging style and way of doing thing.…Martha’s Vineyard had a profound effect on me. The relaxing sea air, the hot sand on the beaches where we loafed naked, the great and continuous drone of the surf, broke down most of the tenseness which life in the cities had given me.…My experiences during wartime had turned me away from myself, had given me objective interests, but I still was a psychological child of the paved streets, provincial and narrow as only they can be. The city, though it had been for me a well of personal stimulation, had left my art barren and aloof from reality. Although I later dealt extensively in my painting with New York life, I did not learn to approach it pictorially until after the little Massachusetts island had freed me from its illusions and opened my mind to receive the great American world beyond it.

While comforting routines can provide the distraction-free time needed to work and create, grinding routines can mire you in intellectual ruts. Sometimes you need to step away, get a change of scenery, and decompress. Since he never stopped working, saying he was on vacation may not be precise, but Benton realized the need to break a grinding routine and let the pounding surf realign his worldview.

Related Video

- MetCollects–Episode 9 / 2014: Thomas Hart Benton’s Mural “America Today” Comes to the Met is narrated by Met curators and describes the history and highlights of the “America Today” exhibit.

- Thomas Hart Benton – The Making of a Mural (10:55) by Encyclopedia Britannica (©1947) chronicles Benton’s methodical mural making process including his use of clay dioramas and egg tempura.

- Thomas Hart Benton “From the Ozarks and Beyond” (9:44) is a concise documentary that chronicles his life and style.

- Robert Hughes – American Visions – Episode 6 (10:58) offers a scathing critique of Benton’s ideas and mural work. While its fairness is debatable, it does capture the ire Benton stoked.

Integrating into Your Curriculum

Artists oftentimes use common visual strategies or signposts to alert viewers to significant details in their art. Here are some ideas for using these visual signposts to unpack a work of art. Remember, the close reading skills in art appreciation are similar to the close reading practices taught in reading.

Literature Links: What piece of literature would you partner with Thomas Hart Benton’s America Today? America Today offers a number of avenues for literary exploration.

- Benton’s autobiography, An Artist in America, is a perfect compliment to this painting. In addition to providing personal accounts from his childhood and early career, multiple chapters chronicle Benton’s sojourns across the country. The sketches from these trips served as the research for America Today so the book adds a behind-the-scenes understanding to the characters in the panels. The two add-on “After” chapters that extend the autobiography offer interesting insight into the aging artist and his relationship with Jackson Pollock. Note, Benton’s paintings were sometimes criticized for being indelicate, chauvinistic, and vulgar. Some of the anecdotes told in this autobiography might warrant the same review.

- Benton is not the first writer/artist to travel the country’s back roads searching for the heart of America. As a 1920s American travelogue, An Artist in America and its corresponding America Today could be fittingly paired with other American travelogues including fellow-Missourian Mark Twain’s Roughing It (©1872), Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (©1957), John Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley In Search of America (©1962), and William Least Heat Moon’s Blue Highways: Journeys Into America (1999).

- Dos Passos’ U.S.A. trilogy chronicles the transformation of American society at the turn of the 20th Century. The series’ fragmented narrative drawing on mass media and popular culture parallels Benton’s style of realism.

- Sinclair Lewis’ Babbit explores how urbanization, industrialization, and technological growth transformed and homogenized American culture in the 1920s. A heavy drinking mid-Westerner with sharp critiques of the literary establishment, Sinclair Lewis’ personal life is likewise rich for comparison.

Writing Opportunity: A loving tribute and metaphorical autobiography. In his art and his writing Benton celebrated the everyday people and families that made the fabric of America. That included for Benton his family pet, a dog named Jake. While he cultivated a roughneck persona, Benton was a sentimentalist at heart and this is never more clear than in the tribute he wrote upon Jake’s passing. Any student, and teacher for that matter, who has ever loved a pet will be intrigued, and even inspired by this tribute. It offers insight into the artist’s attention to detail and his values (this reads a lot like a metaphorical autobiography) and it can be used as a model text for students to write their own loving tribute (and metaphorical autobiography).

Writing Opportunity: A loving tribute and metaphorical autobiography. In his art and his writing Benton celebrated the everyday people and families that made the fabric of America. That included for Benton his family pet, a dog named Jake. While he cultivated a roughneck persona, Benton was a sentimentalist at heart and this is never more clear than in the tribute he wrote upon Jake’s passing. Any student, and teacher for that matter, who has ever loved a pet will be intrigued, and even inspired by this tribute. It offers insight into the artist’s attention to detail and his values (this reads a lot like a metaphorical autobiography) and it can be used as a model text for students to write their own loving tribute (and metaphorical autobiography).

How would you use this painting to build on one of your units of study? Please share if you have other ideas on how to teach America Today by Thomas Hart Benton as an English/language arts lesson plan.

Thomas Hart Benton was as prolific a writer and lecturer as he was a painter, yet he is not widely quoted. To begin to remedy that and to provide a fuller sense of this complicated artist here are a few extra statements from his autobiography, An Artist in America (©1968).

Benton acknowledged, and even celebrated, his combative personality. Throughout his autobiography he gleefully recounts stories where “he gave as good as he got, and then some.” Opposition was a way of life and confrontation an amusing pastime. As Benton explained, “I have had a lot of fun pitting my wits against those who objected to my ways of seeing and doing.” Maybe he was channeling his forefathers, but he tended to rail like a politician. His explanation for moving from New York City back to Missouri in 1936 reflects this tendency. (Does the rhetoric of any recent presidential campaigns come to mind?)

Seeing the country’s ferment and prospect of immense changes in its allegiances, I had the desire to escape the narrow intellectualism of the New York people with whom I associated and to get more closely acquainted with the actual temper of the common people of America. I had no way of doing this in any permanent manner and at the same time be sure of making a living, but I considered the matter extensively. I lived much with those who under the illusory sway of their own logical structures ventured to predict our American future. I didn’t believe them. I didn’t believe they knew what they were talking about. I had myself no certitude about our future. I could foresee nothing. I was aware, however, of the changes coming over the political psychology of our country, and I hankered to be close to the soil on which these would be most clearly operative. (page 260)

While he returned to America’s heartland to find his voice and audience, his work was frequently misinterpreted by the very people he hoped to reach. Time and again he found that truth and reality were subjective. Here he describes the reception of his Social History of Missouri.

When, however, my work was done and I was gone from Jefferson City a storm broke over me, and my illusions about a good many Missouri things were broken with it. I saw that realism was not by any means a completely shared Missouri virtue, and that the habit of calling things by their right names and representing them in their factual character was not wholly agreeable to so many people as I supposed. I awoke to the fact that many of those who came to see me accepted my attitudes simply because of the strangeness and perhaps the fascination of my unusual activities, which made them restrain for the moment the actual mushiness and vulgarity of their own views. But in the end they let it out to me, and I found that a lot of the very people I supposed were favoring me and standing by my work were really miles away from it. I found that my basic attitudes were entirely incomprehensible to many people and that my realism and intention to be faithful to my actual Missouri experience were regarded somewhat as pretensions or poses. The idea that I could be sincere in my attitudes and performances was beyond the reach of a lot of Missouri minds. (page 271)

Midwest high society likewise didn’t meet his expectation, mirroring instead the provincial New Yorkers he so despised. His description of Missouri’s cultural thought leaders is scathing, offering a concise assessment of all who ailed him throughout his career.

One illusion that has been knocked out for good—that is, that the cultivated people of the Middle West are less intellectually provincial than those of New York or more ready for an art based upon the realities of a native culture. Those who affect art with a big “A” do so with their eyes on Europe just as they do in New York. They lisp the same tiresome, meaningless aesthetic jargon. In their society are to be found the same fairies, the same Marxist fellow travelers, the same ‘educated’ ladies purring linguistic affections. The same damned bores that you find in the penthouses and studios of Greenwich Village hang onto the skirts of art in the Middle West. (page 274)

While America Today appears to provide an expansive overview of American society, the dearth of women is to be noted. And those that are shown seem to be relegated to the saint-or-sinner dichotomy. Is this a reflection of Benton’s chauvinism or some other condition? Benton’s statement on the matter opens the door for numerous interpretations.

It will be noticed that my travels around the back roads of America have produced few drawings of women. Women are extremely touchy about being regarded as old-fashioned or outmoded, and unless they are highly convinced of their style or beauty or up-to-dateness they cannot be induced to sit the ten or fifteen minutes it takes to make a drawing. No matter where I have been in America, how far off the lines of regular travel, the popular monthlies of style and chic have preceded me. The women of the backwoods are perfectly aware that they do not appear like the illustrations of these magazines and they are convinced, therefore, that you intend to ridicule when you ask for permission to make a sketch of them. The most well-considered and careful flattery is of no avail in the matter. The minute I get out my pencil women flee. With men it is different. Male vanity soars above all conditions of correctness in dress or manner. The man, like the barnyard rooster, is well satisfied with himself whether he is on a dunghill or in a modern coop. He may see plainly that he is no roaring success, but he puts the blame for that on circumstances and never reads it back into failings of his own. The world may have done ill by him but he himself in his own naked character is all right. As a consequence of this, men are easy to draw. (page 80)

Freudian interpretations aside, “The minute I get out my pencil women flee,” is just one of the many rich statements in this passage. How Benton depicted women can leave one to wonder if it was his gaze, more than his pencil that caused women to flee. In addition to social history murals, Benton interpreted Greek myths in the American landscape. His explicit portrait of a nude Persephone and a leering farmer inspired considerable press and critique, which Benton responded to with his usual homophobic slurs and elitist diatribes.

The other nude, the ‘Persephone,’ had her public adventures also. A couple of years after her first showing, in one of those Bourbon-inspired moments when Truth gets the upper hand of policy, I made the remark before a bunch of newspaper men that the museums were dead places—graveyards, I believe I said—run by a pack of precious ninnies who walked with a hip swing in their gaits and affected a certain kind of curve in their wrists. ‘As for me,’ I let fly, ‘I would rather exhibit my pictures in whore houses and saloons where normal people would see them.’ The New York papers, and then those of the west, made a big to-do over this even though I had made similar remarks before. (page 281)

The nightclub impresario Billy Rose took Benton up on his challenge and the seven-foot long Persephone was exhibited at his New York City saloon the Diamond Horseshoe. Lost in the hyperbole is Benton’s sincere desire to broaden art’s appeal and audience. While Benton remained at odds with the established art world, he continued to explore ways to promote the arts with the general public. As he explained,

Many capable artists were not selling enough pictures for a decent living. There were just not enough picture collectors. If there was a way to bring the great business corporations to the support of art, a way of making them take on the artistic functions, say of the Medieval Church or the great banker nobles of the Renaissance, it would be a great gain, not only for individual artists, but for the place of art as a living factor in our American culture. It would make it a real part of life rather than an insecure and mostly useless appendage. Back in my mind I had long harbored a conviction that unless the arts were returned to some functional place in the full stream of life, they would eventually become mere forms of play, vehicles good for personal release perhaps, but of no real consequence. I had come to know, through their patronage, that quite a number of big businessmen had aesthetic leanings and that a few of them even believed in encouraging a specifically American art.(page 291)

Unfortunately these high hopes were dashed when Benton found that corporate marketing departments were as willing to compromise on their visions as he was willing to compromise on his. Benton’s story about his work with the tobacco industry vividly conveys these clashing realities.

All parasitical games are tough, but I suspect that advertising is the toughest of all.

At the very beginning of my experience with it I ran into a memorable example of that toughness. One of the first to be sold on Lewenthal’s idea that art and business were natural pals was the famous old tobacco magnate, George Washington Hill. After an interview with Mr. Hill and his advertising representatives in New York offices of his company, in which it was decided that a realistic picture of the tobacco industry was to replace the usual photographs of pretty models holding tobacco leaves, I, with two other artists, George Schreiber and Ernest Fiene, was sent down into the fields of southern Georgia. The trip was interesting and the scene full of rich color. We were all very enthusiastic and felt if this was what business wanted to picture there would be no trouble about realizing Reeves Lewenthal’s plans for allying business and art.Now in South Georgia the tobacco is largely handled by Negroes and our drawings and studies were, of course, devoted to them. I made a whole book of sketches, enough for twenty pictures, and we felt sure that among these suitable motif would be found for Mr. Hill’s project. When on returning to New York, I showed my book to his advertising promoters, I ran into a most horrified protestation.

‘You ought to know,’ these fellows said, ‘that you cannot picture Negroes doing what looks like old-time slave work when you are advertising tobacco.’

‘Why?’ I asked dumfounded. ‘You said I was to make realistic pictures and the colored people were doing all the real work down where we were.’

‘Yes, yes, of course, we want realism. That’s why we quit the conventional model stuff and hired you artists, but we don’t want realism that will foul up our sales. The Negro institutions would boycott our products and cost us hundreds of thousands of dollars if we showed pictures of this sort. They want Negroes presented as well-dressed and respectable members of society. If we did this, of course, the whole of the white south would boycott us. So the only thing to do is avoid the representation of Negroes entirely in tobacco advertising.’

‘My God,’ I said to myself, ‘why did these guys send me to South Georgia?’

‘After this I went to North Carolina where the hillbillies handle tobacco and came back with what appeared to be an acceptable picture. It was of an old hill farmer sorting tobacco with his granddaughter, a little girl about nine or ten years old.

‘This is all right, but make the girl prettier,’ I was told.

To insure the prettiness, I borrowed the attractive little daughter of a friend and substituted her for the hillbilly girl. She was very cute and blonde but somewhat skinny. I worked up a highly detailed picture but, when I turned it in, I was promptly informed that while Mr. Hill liked the picture so much that he was going to hang it in his personal office, it was not suitable for public display because the thinness of the little girl might suggest that proximity to tobacco caused consumption.

‘Everything about tobacco must look healthy,’ the advertising people declared.(page 294)

Further attempts to find a happy medium were in vain and this campaign was never fully realized. Benton did however find a role for the arts rallying support for America’s involvement in World War II when he created a series of propagandistic recruiting images that were reproduced through mass media.

While Benton’s outlandish statements and bombastic outbursts effectively grabbed headlines and raised his public profile, they undermined his influence in the established art world. For these and other reasons he was dismissed as a mere Regionalist and relegated to the academic backwaters. While his influence might have been limited, viewing America Today with fresh eyes reveals postmodernist leanings. His recycling of past styles in a modern-day context; his efforts to break down the barrier between fine art and popular culture; and his search for an art that expressed a unique self-identity echo postmodern values. In addition, his use of mass media and cinematic imagery reflect Pop Art concerns. And, his expansive and immersive view of art makes America Today a forerunner of site-specific installations? While Benton was an artist of his time, his impassioned and thought provoking plea for a distinctly American art has as much relevance today as it did in the 1930s.

Now all this anarchic idiocy of the current American art scene cannot be blamed solely on the importation of foreign ideas about art or on the existence in our midst of institutions which represent them. It is rather that our artists have not known how to deal with these. In other fields than art, foreign ideas have many times vastly benefited our culture. In fact few American ideas are wholly indigenous, nor in fact are those of any other country, certainly not in our modern world. But most of the imported ideas which have proved of use to us were able to become so by intellectual assimilation. They were thoughts which could be thought of. The difficulty in the case of aesthetic ideas is that intellectual assimilation is not enough—for effective production. Effective aesthetic production depends on something beyond thought. The intellectual aspects of art are not art nor does a comprehension of them enable art to be made. It is in fact the over-intellectualization of modern art and its separation from ordinary life intuitions which have permitted it, in this day of wholly collective action, to remain psychologically tied to the ‘public be damned’ individualism of the last century and this in spite of its novelties to represent a cultural lag.

Art has been treated by most American practitioners as if it were a form of science where like processes give like results all over the world. By learning to carry on the processes by which imported goods were made, the American artist assumed that they would be able to end with their expressive values. This is not wholly his fault because a large proportion of the contemporary imports he studies were themselves laboratory products, studio experiments in process, with pseudo-scientific motivations which suggested that art was, like science, primarily a process evolution. This put inventive measure rather than a search for the human meaning of one’s life at the center of artistic endeavor and made it appear that aesthetic creation was a matter for intellectual rather than intuitive insight. Actually this was only illusory and art’s modern flight from representation to technical invention has only left it empty and stranded in the backwaters of life. Without those old cultural ties which used to make the art of each country so expressive of national and regional character, it has lost not only its social purpose but its very techniques for expression.

It was against the general cultural inconsequence of modern art and the attempt to create by cultural assimilation, that Wood, Curry, and I revolted in the early twenties and turned ourselves to reconsideration of artistic aims. We did not do this by agreement. We came to our conclusions separately but we ended with similar convictions that we must find our aesthetic values, not in thinking, but in penetrating to the meaning and forms of life lived. For us this meant, as I have indicated, American life and American life as known and felt by ordinary Americans. We believed that only by our own participation in the reality of American life, and that very differently included the folk patterns which sparked it and largely directed its assumptions, could we come to forms in which Americans would find an opportunity for genuine spectator participation. This latter, which we were, by the example of history, led to believe was a corollary, and in fact, a proof of real artistic vitality in a civilization, gave us that public-minded orientation which so offended those who lived above, and believed that art should live above, ‘vulgar’ contacts. (page 318)

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.