John Steuart Curry’s unconventional portrait of the controversial abolitionist John Brown sets the stage for an inquiry study that explores moral responses to righteous causes and fanaticism.

Before launching an inquiry study it is important to have students experience a work of art on their own terms. Use this opportunity to build background knowledge, engage empathy, and spark wonderings. This link offers teaching moves and language for introducing students to John Steuart Curry’s Tragic Prelude. In his Kansas statehouse mural project Curry strove to depict the influential people and events that shaped the character of the state. His unconventional portrait of John Brown proved to be as controversial as the abolitionist himself. Curry’s personal correspondence on this controversy made available through the Smithsonian’s online archive offers a unique opportunity to witness this heated debate firsthand and for students to consider difficult questions around their own moral responses to righteous causes. It’s easy to point at people who adamantly hold an opposing viewpoint and label them a fanatic. But, what do you call a fanatic who shares your values?

Do you know Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art? It is a veritable intellectual national park and a real treasure. The John Steuart Curry and the Curry Family papers offer great opportunities to sift through primary source documents and engage in authentic historical research. Just as John Brown’s reputation and legacy was reappraised over time, so too did thinking around Curry’s Tragic Prelude. Reading these letters, writings, and newspaper clippings shows how politics and public opinion can cause our understanding of historical “truths” to shift over time. (Note: Reading cursive writing can be especially challenging for digital natives. Fortunately, most of these writings are typed.) Here is a gallery of Curry’s personal correspondence. Click on an image to look closer.

Do you know Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art? It is a veritable intellectual national park and a real treasure. The John Steuart Curry and the Curry Family papers offer great opportunities to sift through primary source documents and engage in authentic historical research. Just as John Brown’s reputation and legacy was reappraised over time, so too did thinking around Curry’s Tragic Prelude. Reading these letters, writings, and newspaper clippings shows how politics and public opinion can cause our understanding of historical “truths” to shift over time. (Note: Reading cursive writing can be especially challenging for digital natives. Fortunately, most of these writings are typed.) Here is a gallery of Curry’s personal correspondence. Click on an image to look closer.

- A series of letters from Kansas cultural and political leaders pitch the idea of the murals and describe the behind the scenes efforts and motivations for launching the mural project. (Correspondence, Box 2, Folder 39, note especially thumbnails #1 and 2.)

John Steuart Curry’s Description of Murals for Kansas State House, circa 1937–1942 chronicles what the artist intends to depict. (Notes and Writings, Box 4, Folder 23)

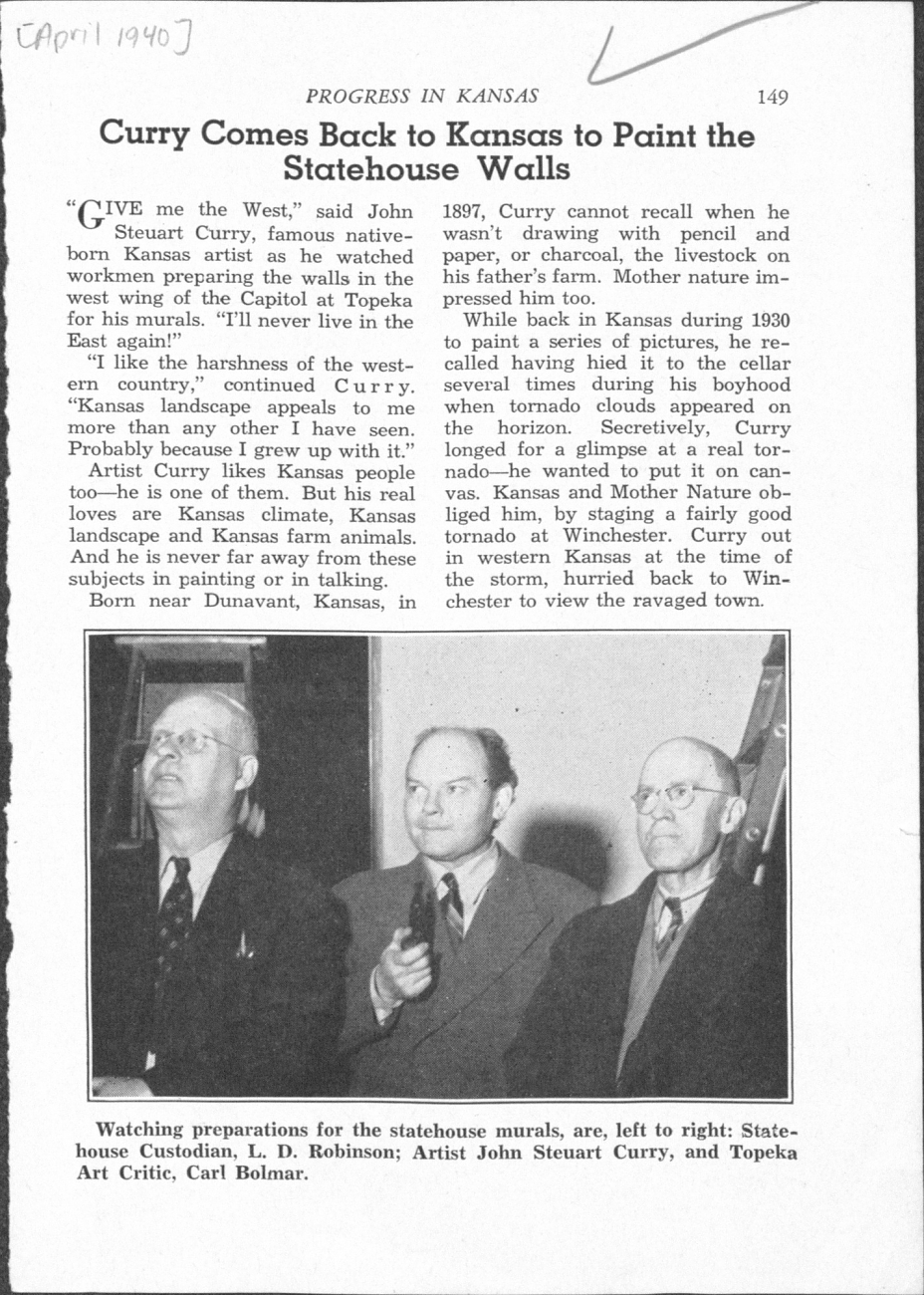

John Steuart Curry’s Description of Murals for Kansas State House, circa 1937–1942 chronicles what the artist intends to depict. (Notes and Writings, Box 4, Folder 23)- “Curry Comes Back to Kansas to Paint the Statehouse Walls,” Progress in Kansas, April 1940 expresses everyone’s high hopes at the beginning of the project. (Clippings 1940, Box 4, Folder 63)

- John Steuart Curry’s John Brown subject file includes the pictures and writings Curry collected as he prepared Tragic Prelude. Note that the Kansas John Brown was clean-shaven and that his characteristic, and expressive beard was only grown later to disguise his appearance. (Subject Files, Box 3, Folder 58)

- A series of letters give the first hints of problems in removing decorative marble slabs to make room for the murals. (Correspondence, Box 2, Folder 41, note especially thumbnails #10–11, 18–19, 30, and 45–49.)

- “Artist Curry Brushes Up on Subject of Pigtail Kinks,” _____ Sentinel, November, 11, 1940 describes how a farmer’s critique of Curry’s pigs sends him out to the farms to observe and sketch. (Clip

pings 1940, Box 4, Folder 63)

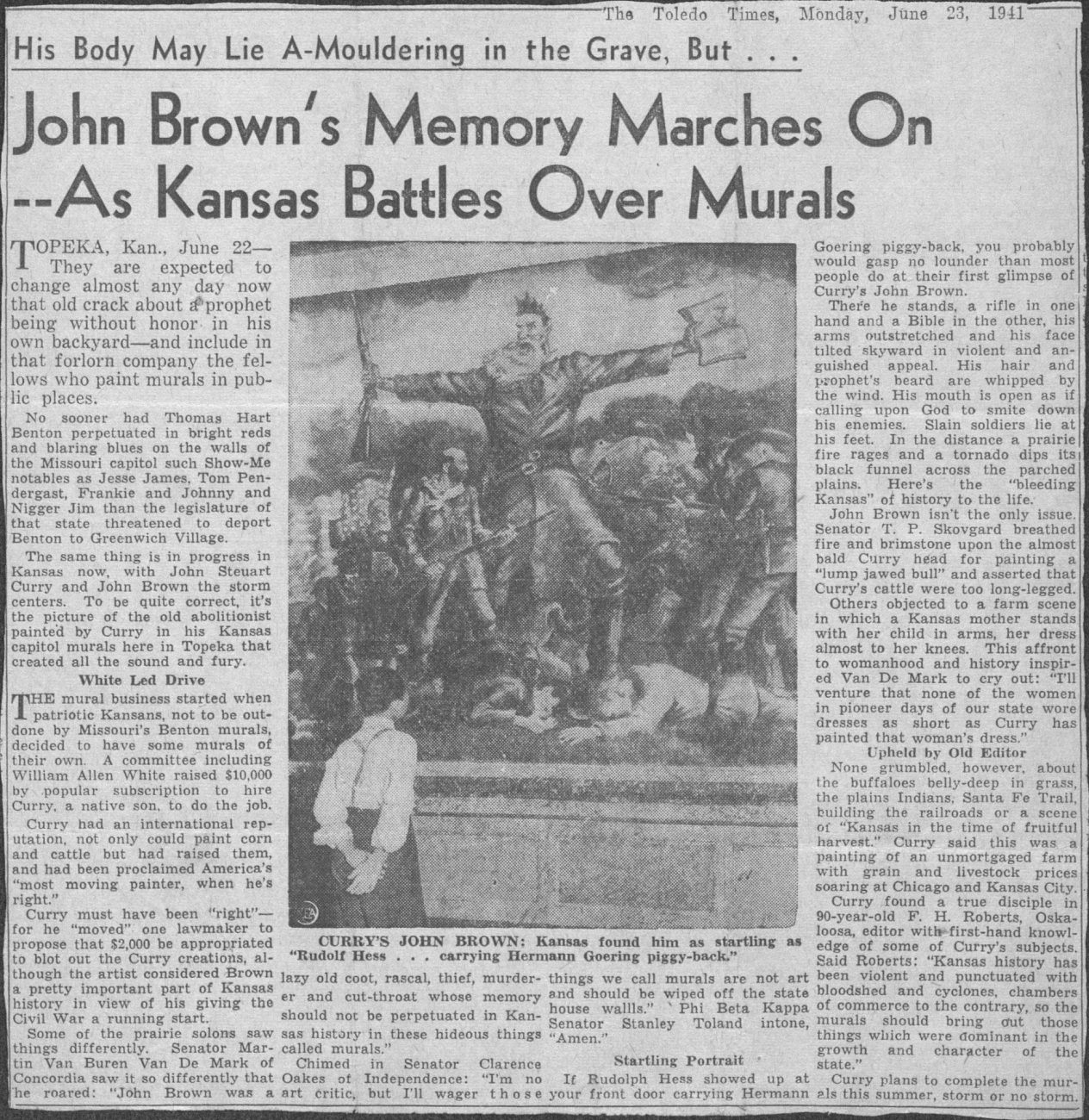

pings 1940, Box 4, Folder 63) - “John Brown’s Memory Marches On—As Kansas Battles Over Murals,” The Toledo Times June 23, 1941 chronicles the growing political discord around Tragic Prelude. (Clippings 1941, Box 4, Folder 64)

- A series of letters between Curry and supporters and opponents of the mural project offer insight into the rising tensions. (Correspondence, Box 2, Folder 44, note especially thumbnails #8, 12, 13, 20, 22–23, 21 & 24, and 25.)

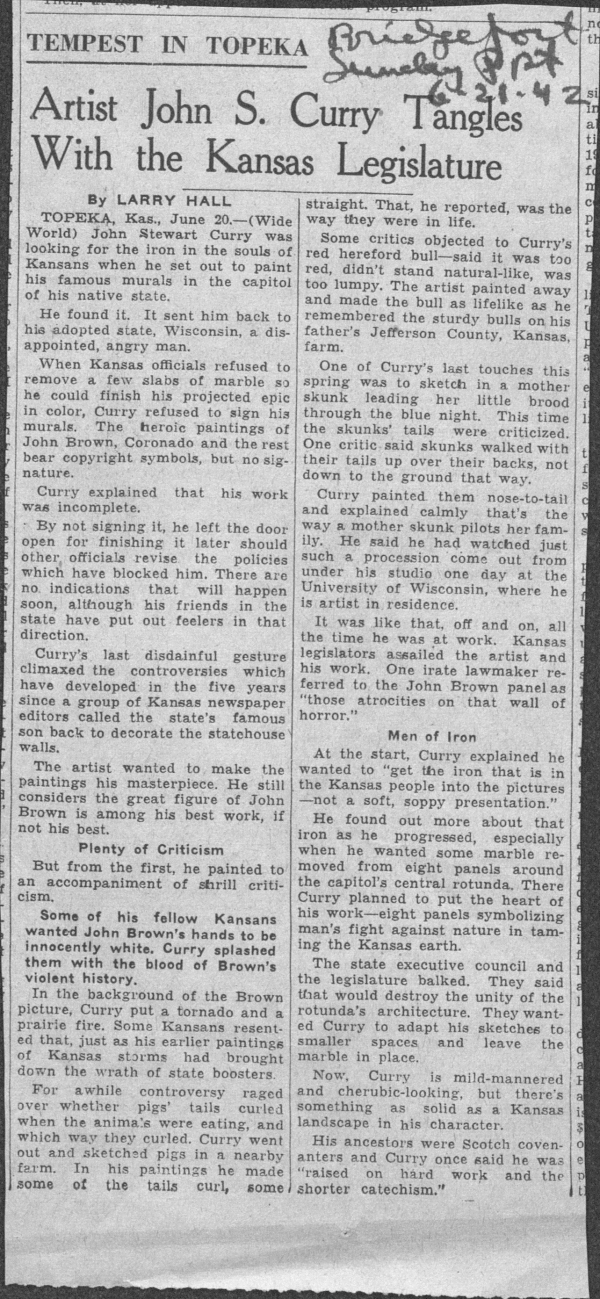

- “Artist John S. Curry Tangles with the Kansas Legislature” Bridgeport Sunday Post, June 21, 1942 details the mural controversy and why they were left unsigned. (Clippings 1942, Box 4, Folder 65)

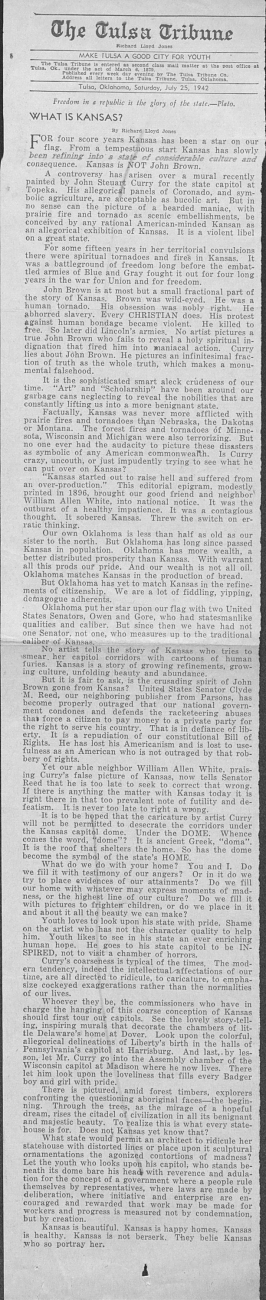

- Richard Lloyd Jones’ editorial “What Is Kansas?” The Tulsa Tribune, June 25, 1942, condemns the murals, especially the depiction of John Brown. (Clippings 1942, Box 4, Folder 65)

- Curry responds to Richard Lloyd Jones in a personal letter. (Correspondence, Box 2, Folder 45, note thumbnail #35)

- A series of letters between Curry and supporters and opponents of the murals detail the mounting acrimony, the frantic efforts to keep the project on track, and Curry’s failing health. (Correspondence, Box 2, Folder 46, note thumbnails #1, 5, and 18.)

- Thomas Hart Benton’s “Implications of Artist’s Reaction to Lack of Sympathy from His “’Ideal Audience.’” Kansas City Times, November 27, 1946 is an eloquent tribute from a dear friend and acclaimed artist who suffered similar criticism for his murals. (Clippings 1946, Box 4, Folder 68)

- “SAGE of the SAGA,” Topeka Capital Journal, October 16, 1977 describes how the artist Lumen Martin Winter was commissioned to complete the Curry murals. (Clippings 1976-78, Box 4, Folder 74)

- John Steuart Curry’s state house murals are declared one of the eight wonders of Kansas.

Have small groups read different letters and news accounts and plot key events on a class timeline that maps how support for the mural project evolved. (Also let students revel in the snarkiness as the drama builds. Curry’s zingers reflect his emotions and will remind students that history is about the struggles of real people.) As students share, capture their questions and points of interest. In addition to exposing varying, and deeply held, views of historic people and events, these documents provide insight into the use of argument writing, proxy arguments, and political maneuvering. If time and interest permits, have students research and respond to their questions.

Have small groups read different letters and news accounts and plot key events on a class timeline that maps how support for the mural project evolved. (Also let students revel in the snarkiness as the drama builds. Curry’s zingers reflect his emotions and will remind students that history is about the struggles of real people.) As students share, capture their questions and points of interest. In addition to exposing varying, and deeply held, views of historic people and events, these documents provide insight into the use of argument writing, proxy arguments, and political maneuvering. If time and interest permits, have students research and respond to their questions.

The Question Formulation Technique (QFT) can help turn art observations and wonderings into inquiry-based research questions that build on student insights and interests. For ideas on how to structure inquiry circles see Stefanie Harvey and Smokey Daniels’ Comprehension and Collaboration: Inquiry Circles for Curiosity, Engagement, and Understanding.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.